Despite living near the Yamuna, farmers don’t touch the water; others think it will be drinkable soon

Having spent decades toiling over a small plot of land they call their khet (farm), a grizzled Dharampal seems older than the 60 years he claims to be.

About 30 of those years have been spent on the banks of Yamuna river. He has not known life without the smelly, disease-giving water body. As we tell him of the promise made by a minister, he is quick to dismiss it. This promise is of providing clean drinking water from the Yamuna in just over a year by Union Minister Nitin Gadkari, during the foundation laying ceremony of Namami Gange project in Agra in January.

The Centre’s flagship Namami Gange Programme was approved by the Union Government way back in June 2014 with a planned budget of Rs 20,000 crore.

For Dharampal, this is just one of many promises he has heard in the past 10 years.

His wife Omvati tilling the land, weeding the grass around her precious spinach, tells us that she never lets her kids near the water, let alone into it. Now, with all of them married, despite the precaution, her family and at least 20 others are often plagued with typhoid, malaria and tuberculosis, which they believe afflict them because of where they stay. Still, for her and Dharampal, living here is presently the only option.

The National Green Tribunal (NGT) in 2015 banned growing vegetables near the Yamuna floodplains, because of high levels of pollutants in the river. A 2012 report by the Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) found heavy metals in vegetables grown along the floodplains.

Farmers, though, still grow vegetables and some are reported using contaminated river water to wash the produce along with spraying insecticides and pesticides to facilitate growth.

This couple, however, use a tube well that they and the other families dug together. It is supported by a diesel motor. Diesel is also their source of electricity.

The people here have not received much help from authorities, as can be seen. And their vicinity has only gotten worse with pollutants.

Since the Yamuna Action Plan commenced in 1993, nothing much has changed. “Paani main kuch badlav nahin aaya hain, aur jab badh aati hain toh sab pani hamare bag main ghus ke sub kharab kar deta hain” (The water has not changed and when the Yamuna floods, it ruins all our produce) says Dharampal, who is sick of authorities’ promises.

The first phase of the Yamuna Action plan was scheduled for completion in April, 2002, but the planned projects continued until 2003.

A research paper by Deepshikha Sharma and Arun Kansal of TERI University titled The Status and Effects of the Yamuna Action Plan, talks about the first two phases of cleaning the Yamuna and how much money was put into it.

The Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) had provided financial assistance in the form of soft loans, with beneficiary states being Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Delhi. The approved cost of Yamuna Action Plan (YAP) I was Rs 590 crore).

We are confident Ganga will be 100% clean by March 2020. For this Yamuna also has to be clean. It’s my assurance to you that Yamuna will be clean. – Nitin Gadkari, Union Minister

People are saying that the Yamuna is polluted. Look at it, it is clean and calm. It is the minds that are polluted. – Venkaiah Naidu, Vice President of India

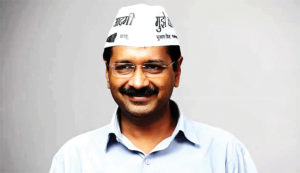

As there have been concrete improvements in other spheres during AAP govt, we will work hard on cleaning drains and Yamuna. It will take time. – Arvind Kejriwal, CM of Delhi

In May 2001, an additional amount of Rs 220 crore) was approved for the extended phase under this proposal. Of this, Rs 22 crore was allotted to Haryana, Rs 160 crore to Delhi and Rs 29 crore to UP. In addition, an amount of Rs 40.5 million (approx. Rs 4 crore) has been provided for the fee payable to the Indo-Japanese consultant consortium.

The total cost of YAP I along with the additional package was Rs 730 crore. YAP II was launched in December 2004.

The total budget sanctioned for YAP II was Rs 600 crore which was distributed to Delhi (approx. Rs 380 crore) UP (Rs 120 crore) and Haryana (Rs 60 crore). For capacity building exercises, Rs 50 crore was allocated. Since the work was not completed in time, the project was extended till March 2011. The total sewage treatment plant (STP) capacity sanctioned was 189 million litres per day (MLD).

Phase III was approved for Delhi and launched in 2013 with an estimated cost of Rs 1,656 crore.

While a total of Rs 2,986 crore has been spent on the project, the work has a long way to go. Of the 11 projects flagged off under the Namami Gange programme in 2019, a majority are for improved sewerage infrastructure.

Even the plan for Phase III was to build newer sewer lines and modernising the existing sewage treatment plants across Delhi’s three drainage zones —Kondli, Rithala and Okhla.

Manoj Misra, founder of the Yamuna Jiye Abhiyan, says that the Delhi Jal Board’s performance is a joke, adding that engineers are interested only in the creation of new sewerage assets, while bothering little about how the existing ones are doing.

A report states that Delhi generates around 600 million gallons of sewage every day, but sewage treatment plants (STPs) set up in Delhi have a capacity to treat only 512.4 million gallons of waste.

Where does the rest end up? An RTI reply in 2015 had revealed that around 2,225 MLD of untreated water either seeps into the ground or is discharged into the Yamuna every day.

Misra, whose YJA has been running advocacy campaigns — for the life of the Yamuna river since 2007, along with constant monitoring of data — says that Gadkari’s other statement boasting that the river Ganga will be cleaned up to 70-80% in the next three months and fully by March 2020 was “another gas”.

He says that rivers “are crying for the restoration of their natural flow” and absence of this means “any talk of sustained rejuvenation is a lie”. He emphasises that unless “true flow becomes the norm, all claims and targets are meaningless, to say the least”. He added that both Ganga & Yamuna Action Plans ignore the need of flow restoration, which in consequence means the projects are fated to become “monumental failures”.

At present, Misra points out, the Yamuna is far from being the clean river the Centre and Delhi government promise. In fact, he calls it a “toxic cocktail of poorly treated and untreated mix of sewage (including household chemical rejects of various kinds as well as detergents), industrial effluent and even biomedical waste”.

This he says has also resulted in the Delhi portion of the Yamuna being reported with super bug – those resistant to antibiotics – by scientists at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

The study had found dangerous amounts of medicines flowing into the river. And how do they come back to us? Through milk and vegetables contaminated by this river water.

Currently, people don’t quite believe the promise that they can drink from the Yamuna, and perhaps even when delivered, the fear of catching an infection would be hard to shake off. But governments missing deadlines is no oddity, so the hard choice may be a long distance away.

Moolah spent

Under the Yamuna Action plan, a joint project between India and Japan, an estimated Rs 2,986 crore has been spent.

Down to Earth marks the total expenditure incurred by the government on Ganga cleaning projects since 1985 at over Rs. 4,000 crore.

In 2014, the union government approved Rs 20,000 crore for the project named Namami Gange.

According to the Revised Estimates 2018-19 in the interim Union Budget for 2019-20 presented in Parliament, Namami Gange has been allotted Rs 2,300 crore.