Killer pollution, eternal corruption, social despair and economic frailty are some of the reasons why indians do not mind spending thousands on an english profiency test

In October, Priyanka Mathur*, who works in a multinational company, made a third attempt at the International English Language Testing System (IELTS), a global test of language proficiency. She needed to score an 8 on one module and 7 in three others to qualify for applying for Canadian Permanent Residency. Other criteria are good educational qualifications and work experience.

Her first attempt saw her writing skills fail her. In the second, again. After months of practice, she finally got the required 7 but in turn her speaking slumped below her earlier score and what was required — by a hair’s breadth.

“Now I’m done,”Priyanka says.

The IELTS tests is conducted four times a month by two institutions in India: the British Council in 42 locations across India, and the IDP, which offers the tests across 50 city locations in India in 34 IDP Centres. Each test costs Rs 12,650 and there can be 400 aspirants at a time at any given centre. One can imagine how much is earned from people who want to emigrate or study abroad.

IELTS is the most widely used test of English for migration to Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the UK.

But forget the fact that one takes the test and is graded and certified, so to speak for their knowledge of English. What is confusing is that after two years the same results become invalid. Suggesting that within those two years the aspirant would have forgotten the level of English they were certified as having.

One might even ask: Why go through the trouble? For Mathur, moving to Canada is a need, she says. “For better employment and a better life, I want to move. By better employment I mean where employers respect their employees’ personal lives and don’t treat us like slaves”. There’s also a need, Mathur adds, to be in a country which is not wallowing in corruption.

According to the Corruption Perception Index 2017, India ranking at 85, is one of the “worst offenders’ among Asia-Pacific countries. The Berlin-based Transparency International (TI) put India below Ghana and above Morocco, in a list of 183

countries.

Even in the ‘World Happiness Report’, India was depressingly low at 133 out of 156 countries. Its website says that all the countries topping the charts “tend to have high values for all six of the key variables” which support well-being: income, healthy life expectancy, social support, freedom, trust and generosity.

And in this, surprisingly, even Congo, a country still recovering from a bloody civil war, is marked at 132 — one place above India. One below is Niger — one of the countries marked as the least developed by the UN. With her two young children, Mathur believes a country like the one she wants to move to will give them a better opportunity in life.

She also emphasises on the need for “a life free of pollution”.

And who can question that? A recent study by the World Health Organisation shows 1.25 lakh children in India below the age of five died in 2016 due to the impact of polluted air. Furthermore, almost one in five children who die from toxic air exposure across the world is from India.

The report titled ‘Air Pollution and Child Health’, found that polluted air inside households contributed to the deaths of about 67,000 children below the age of five in India in 2016. The study also said that outdoor air pollution, specifically PM2.5, caused by vehicular and industrial emissions and a host of other factors, accounted for nearly 61,000 deaths among children of that age group in 2016.

The capital city is currently reeling under a severe deterioration in air quality. Last year, the situation was so bad that being outdoors was equated with smoking 40 cigarettes a day. And yet again we are back to the same end-of-days doom and gloom.

In the case of students, most cite the need to go abroad because of better academic offerings, better teaching methods which do not wholly depend on a classroom learning but going out and learning practically.

Ria Deb* knows the fee for the college she wants to get into is phenomenal. At Euro 18,000 a year, it is something Deb says she cannot afford without a scholarship. But her determination to get through is because… “I want to be as qualified as I can be for the profession I want to pursue.”

With post-graduate courses in journalism being few in India, Deb says the course that she wants to apply to is an institute that has a global reputation, which has a “very specific and detailed course structure, and makes for a lot of exposure.”

In our country’s case, the IISc ranked the highest in terms of Indian universities at a dismal 251 out of the 300 ranked. The reputed IIT was ranked 351 in the world university rankings. Students also believe that the prospects of earning higher in an increasingly expensive world can only be achieved if they leave the country and pursue studies outside.

Reuben Sajit gave his IELTS exam in October and is still awaiting the results. The listening module, he says, had a “made up accent” he adds laughing, and that it didn’t match any of the TV shows he has watched. For him, going abroad is a necessity, as the data science course he is applying for has not “hit India yet”.

This doesn’t mean companies in India are not looking for people with the same skill. Sajit will still look for a job in the country he would eventually study in to make up the amount invested, before returning to India, which clearly does not pay enough.

India comes under the ‘Mostly Unfree’ index of economic freedom, at 130 — one rank above Pakistan and one below Kenya. The Index covers 12 freedoms — from property rights to financial freedom — in 186 countries.

For over two decades, the Index of Economic Freedom has measured the impact of liberty and free markets around the globe. It compares countries and ranks them according to the economic opportunity, individual empowerment & the prosperity it offers.

But Indians’ desire to go abroad is not matched by other countries’ desire to embrace us. The Trump administration in the US is making it harder for Indians who are the biggest recipients of the H1B visas to enter the country.

The UK has made it apparent that it is against migrant students. This, even when international students are worth £20bn to the UK economy. The report from the Higher Education Policy Institute says that on top of tuition fees, their spending has become a major factor in supporting local economies.

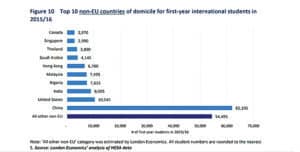

London alone gains £4.6bn, most of it contributed by China, with 62,105 first-year Chinese students entering UK higher education in 2015/16. The US and India were the next most prolific, with 10,545 and 9,095 first year students in 2015/16, respectively.

Clearly, India is still not able to meet the aspirations of its youth. Whereas the most desirable countries can desist and resist from welcoming whomever they want.

(Names changed to protect identities)