The technique of trans-cranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is now being used to loosen cocaine’s nasty grip on addicts

It is difficult to quantify the totality of human potential lost every year to addictions. This includes behavioural ones such as gambling, video gaming, shopping, incessant internet surfing as well as maligned substance abuse dependencies — a spectrum ranging from smoking, alcohol, recreational drugs to hard drugs like heroin and opioids.

In fact, an opioid addiction crisis is sweeping the United States, with 72,000 people dying from drug overdose in 2017. Throughout 2017 and 2018, The New York Times reported on the toll this epidemic is taking on the country and the systemic failures that have enabled it.

The World Drug Report 2018 states that 18.2 million people around the world are cocaine users; of these one in six is addicted with the largest proportion of addicts being in North and South Americas. A little over a million users are in Asia, where consumption has steadily increased since the late nineties.

Addiction is a disease

Non-addicts may have a stereotypical mental image of an addict — someone with less willpower than them. The addict’s inability to say no to what is clearly causing harm is perceived as a flaw. This view is erroneous and no good comes out of trying to guilt trip another to stop taking the next drink, smoke or joint.

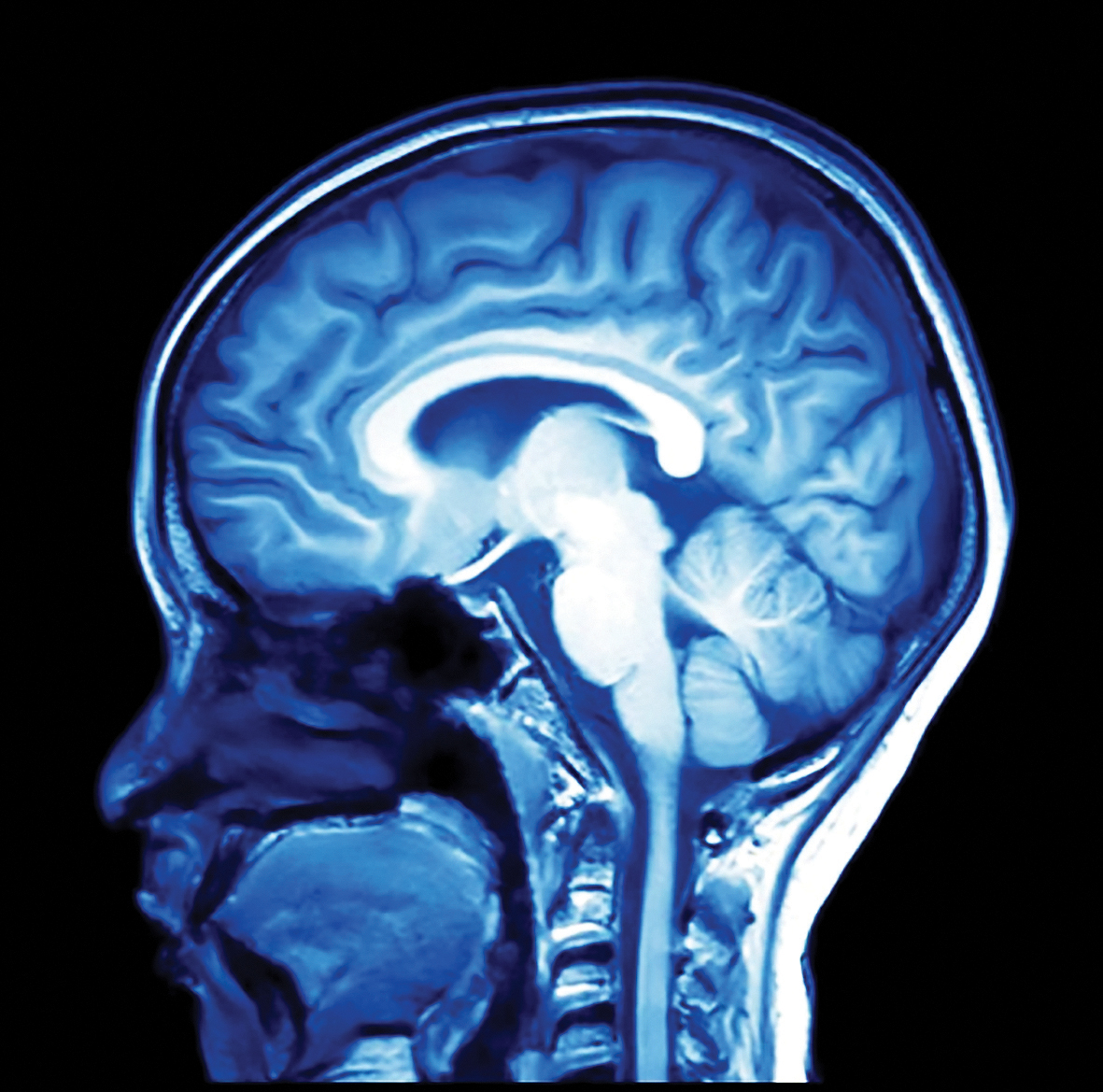

Addiction is a disease. It works by hijacking the reward pathway of the brain located within the brain’s limbic system. The limbic system is a set of interconnected regions in the front part of the brain (pre-frontal cortex) that enables us to (i) experience pleasure, (ii) focus and make decisions, and (iii) consolidate memory. When one is exposed to stimulants like comfort food, sex, music, dance, social interactions or exercise, a part of the limbic system called nucleus accumbens (NAc) is flooded with the neurotransmitter dopamine. Cells in NAc, when simulated by dopamine, produce feelings of pleasure and satisfaction.

Simultaneously, other parts of the limbic system are working to focus on the activity at hand and remembering its pleasurable consequences. So we learn what causes us pleasure and seek it out. For most activities, pleasure is also a function of practice. If you repeat something often enough, you become good at it; it becomes fun.

In the presence of stimulants like drugs, a short-circuit is immediately established in the reward pathway. Take cocaine as an example. Once it is consumed, about 10 times more dopamine is released instantly into the NAc, giving the user enormous feelings of pleasure or a ‘cocaine-high’.

In short, dopamine overload results in enhanced pleasure and the user’s brain records cues (people, places, and things) associated with this occasional recreational drug use. After a few days, the user does it again. Then a few more times. Each repeated exposure strengthens the memory-connect associated with the high and progressively affecting the brain’s decision-making ability. After continued short-term usage, one in six people will end up addicted — they no longer control their urges.

Based upon the severity of exposure, cocaine affects the brain at three levels. Flooding of the NAc with dopamine is the immediate short-term response. Once addicted, at the intermediate level, repeated exposure alters gene expression. Chronic exposure has the most severe outcome as the physical shape of the nerve cells in the NAc begins to change. They sprout new offshoots that grow towards the brain’s memory centre, strengthening the link between memory and pleasure This is a possible explanation as to why relapse is frequent after people quit drug use. It is also why cocaine addiction is particularly hard to treat.

Cocaine addiction

In recent years, the known non-invasive technique of transcranial magnetic stimulation is being applied to treat cocaine addicts.

In 1985, Baker et al. showed how an external magnetic field could be used to stimulate both nerve and brain tissue. Since its introduction, in ensuing decades, transcranial magnetic stimulation or TMS has proved to be an important tool in neurobiology. The underlying principle is one straight from fundamental physics — a changing magnetic field will induce a current in a nearby conductor and its rate of change will determine the strength of induced current. Delivering these magnetic (single or evenly spaced) pulses to the cranium (skull) can therefore be used to selectively activate or deactivate specific brain regions or neuronal tissue. Interestingly, on the one hand, this feature of selective stimulation of specific brain regions using TMS has allowed researchers to study brain function and on the other hand treat neuropsychiatric disorders, in particular depression.

Addiction messes with reward pathways of the brain. Also, in drug-seeking behaviour, part of the brain’s signaling pathway that tells one to stop malfunctions. In 2013, a study published in Nature by Antonello Bonci’s lab revealed how targeted stimulation of the pre-frontal cortex, in-vivo using optogenetics, decreased drug seeking behaviour in cocaine-addicted rats with few side effects on non-compulsive reward-related behaviors.

Simply put, could repeated stimulation of the pre-frontal cortex bring back damaged neural pathways to life and stop intense drug cravings in humans without debilitating side effects? Could relapse be history? Yes or no, in the very least, it was worth a shot. That TMS would be a pragmatic approach to treat human patients over optogenetics was quickly realised by Luigi Gallimberti in Padua, Italy.

Three years later, in collaboration with the Bonci Lab, they published their first preliminary study showing the reduction of cocaine craving behaviour following stimulation of the pre-frontal cortex using TMS. “Study limitations need to be acknowledged, in particular: the small sample, the open-label design, the lack of urine drug screen for benzodiazepines, and the short duration of treatment.” Still, the study has significant merit. “In fact, this is the first clinical report indicating that TMS treatment resulted in significant reduction in cocaine use. As such, this study holds critical clinical importance. While reduction in craving is important; cocaine abstinence represents the most critical achievement goal from a clinical standpoint,” as readily acknowledged by the authors themselves.

Promising future

Two years on from the first clinical study, where do we stand?

A recent review published in May 2018 evaluates the current standing of TMS vis-a-vis treatment of drug-seeking behaviour. Since the publication of the first clinical study in 2016, only five other studies have been published. It is striking that all of them have low numbers, resulting in overall weak statistics. Another major drawback is the lack of a standardised treatment protocol. Despite these problems there is evidence that people have benefited from TMS treatment.

Of course, more concrete work needs to be done to pass a verdict on TMS and its efficacy for treatment of cocaine addiction. A consistent research methodology would be good or else studies will remain easily dismissible in both serious and casual discussions. Scientist working in the field need to tidy up for concrete and decisive conclusions to be reached.

But all of one’s statistical concerns should not let one forget that real people benefit from these treatments. There is a very real possibility that someone somewhere may get their life back from the grip of addiction. A poignant account of recovery from cocaine addiction through TMS treatment is recounted in a National Geographic article.

Addiction is a complicated and prevalent disease and every one of us is vulnerable. This complexity and severity means more work needs to be done to understand root biological mechanisms and develop treatment approaches. Though it would be premature to declare TMS a success for treatment, the technique does show promise.

One day, relapse might be history. With millions of lives at stake, it’s a battle worth fighting.

www.newslaundry.com