The Seemapuri slum area has been fighting lonely battles as it has never once seen its MP after the last election

When someone says Delhi, what comes to mind is imposing buildings, five-star hotels, clean roads and the swanky metro railways. But far removed from all this, in one corner of the North East Delhi Lok Sabha constituency, lies Seemapuri, an area that is completely opposite to the idea of a Capital city.

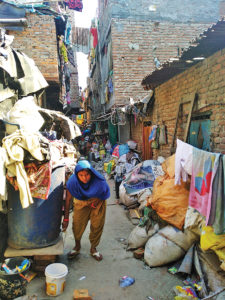

A short auto ride away from Dilshad Garden, one is greeted with a foul stench, and heaps and heaps of rubbish accumulated on the side of the main road. A huge mosque dominates the skyline, but behind it are lanes so narrow that only one person can walk at a time.

The locals call it ‘Nasbandi Colony’, as the houses here were built by Congress in 1976 during the Emergency, for those who fell victim to the alleged mass vasectomy drive conducted by the then government. Now, the Seemapuri slum is inhabited by Bengali Muslims, displaced from different parts of West Bengal and Bangladesh, working as scrap collectors and dealers.

The first man Patriot met at a small tea shop was Mahesh. He has been staying for more than 20 years in this colony, working as a scrap collector. “For the past so many years that I have been living here, the last 18 months have been the worst for my business”, he says. “The shutting down of the factories in Vishwas Nagar has hurt our income a lot. Earlier we used to earn more than double of what we earn now”, he says.

At the end of 2017, many factories in North East Delhi were shut down when the EDMC authorities deemed them illegal. “They shut down some 4,000 factories in the area”, he says. The waste that used to accumulate from factories manufacturing pipes and electric wires proved to be a gold mine for Seemapuri’s scrap trade. “From pieces of pipe to small shards of bulb wire, from plastic to glass, we used to get so much material from these factories”, says Mahesh. “Now, after the shutdown, we earn just enough to feed ourselves and our families”, he adds.

A little further down the alley, after crossing heaps of scrap accumulated by the families who live here, is a small shop owned by Mohd Akhlaq and his mother Salima. “This business was started by my parents more than 40 years ago, when they came here from Kolkata”, says Akhlaq. “I was born and brought up here, and am running the business for the past 25 years, but the last three years have been the worst for me,” he says.

“Even in 2016, I used to earn in thousands a month, just by dealing in scrap, and now I hardly earn Rs 50 a day”, he says. This, according to Akhlaq, is because of three factors. “First the implementation of demonetisation and then the imposition of GST — these were like two slashes of a sword on my neck. People stopped transacting in cash, and I had to pay so much more taxes, and hence I started incurring losses”, he adds. However, the last and sharpest nail in the coffin was the shutting down of the Vishwas Nagar factories. “My profits have been more than halved, and it is all because of the EDMC and the Indian government”, he says.

A few shops further down, inside a small room filled with all sorts of old electrical appliance parts and other metal scrap, is the shop of Mohd Maqsood, another scrap dealer. He too has been running his business for the last 26 years, ever since he settled here from Kolkata, as he heard from his friends that this area was a gold mine for kabadis. He echoes the same sentiments as Akhlaq. “You ask any trader here — everyone will say how they have been adversely affected by the triple blow of demonetisation, GST and the shutdown of factories”, he says. “My income has almost halved, but my expenditure has increased. Be it the electricity bill or the water bill, everything has increased. Plus, I also have to pay the scrap collectors”, he says.

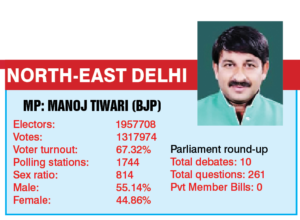

All dealers and collectors we spoke to echo the same thoughts — they have incurred huge losses and their business is at an all-time low. Another thing they all agree upon is their disillusionment with their sitting MP, the current Delhi BJP chief Manoj Tiwari. “The last time we saw him was during the previous elections. In the next five years, we never saw him here. He has never come to ask us about our problems”, says Fatima Begum, a scrap collector.

With elections on the horizon, the inhabitants of Seemapuri slum are eagerly looking forward to the post-election scenario, hoping that their power to vote might bring them a better future. However, for 70-year old Salima Begum, sitting in front of her shop under the hot summer sun, “No matter who comes to power, people like us will have to shed our blood and sweat, and make ends meet.”