You’d expect idols and artefacts to be stolen and looted only in countries in the midst of war and not in India which is largely peaceful.

But a recent study by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) will surprise you. It estimates that 50,000 idols and artefacts had been smuggled out of India between 1947 and 1989. Additionally, between 2008-2012 alone, over 2,200 sculptures and idols were stolen from Indian temples where they were still being worshipped.

These thefts were likely part of the illegal trade of arts and artefacts which, according to estimates by the advocacy group Global Financial Integrity, is estimated to be worth $6 billion a year.

US-based artist Shaurya Kumar, who was born in Delhi, touched upon this theme and brought it to light in his recent exhibition in New Delhi called ‘There is no God in the Temple’.

The oeuvre of Kumar focuses on issues of the objects and non-objects and questions the role of individuals and institutions that assign them their new meaning.

The title of the exhibition — ‘There is no God in the Temple’ – is drawn from a poem by Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore and the work addresses many topics in different ways.

It considers the modern ruin, and the ruin’s relation to modernity and urbanisation. It explores the role of military and militia where specific works of art are targeted and destroyed when the new regime is against the philosophy of the work itself (in the case of bombing of Bamiyan Buddhas, destruction of artefacts in Kabul and Beirut Museum, Palmyra and Mosul among others). Lastly, it explores the effects of transposition of an object from its original context to the new environment.

“My work looks through objects, within and beyond, and questions not their physical form but the purpose they serve. It probes subject-object relationship in a particular time and context. Much of my work, thought and research in recent projects has been a response to this subject-object dialogue and to the contemporary state of ruinous affairs,” he explains.

“I have always been very interested in understanding the role of objects in the study of history. Without tangible, material things, we would have no knowledge of our past. Some of this interest began when I first moved to the US for post-grad education. I had to pack up my life in Delhi in two suitcases and call the US the new home. What I would take, what I would bring, preserve and archive is how I considered defining my memories and histories. People do this with purchase and collections of mementos and souvenirs when they travel. Objects however only are symbols of a journey or an experience,” he adds.

Reflecting on the loss and destruction, Kumar’s work addresses how our understanding of history, culture and religion is constantly reinterpreted and distorted – with the presence of objects and the absence of them.

He is particularly interested in addressing the ‘loss of aura’ when the ‘original’ is transformed in its meaning and narrative due to transposition, destruction and looting: a temple without a god or when a god is placed in a museum without any context of history or social landscape.

The idea to explore the relationship between the subject and object, the worshipper and worshipped, occurred to him when he witnessed five Indian women walking into the museum of Art Institute of Chicago on the eve of Ganesh Chathurthi, the birthday of Lord Ganesha.

The women didn’t enter the museum with a procession, trumpets or even incense sticks. But rather with one single flower that they placed in front of the idol, and in an act of reverence, attempted to touch his feet. The guard, following his orders, instantly reacted and stopped them from doing so, pointing to the sign “Do Not Touch”.

The sculpture, as explained to them, was not to be worshipped, as it was no longer a religious object, but rather a sculpture and the property of the museum. He was to be considered only as an image carved out of sandstone and not an idol from their temple.

“Now, the birthday is usually celebrated with extreme passion and excitement, bringing in crowds in millions. However, these women, for the first time, decided not to go to the temples nearby for this celebration, but rather come to the museum to mark his birthday. The reason for this was new. They had recently discovered that the sculpture of Ganesh that stood silently in the gallery was in fact the one that came from their village in Madhya Pradesh, from the very temple where their mothers and forefathers had worshipped for centuries,” he explains.

According to Kumar, that idol of Ganesha is a world which is representative yet which erases its context of origin. It represents the total aestheticisation of the object, where the original context is not restored, but a new one is created.

Born in 1979 in New Delhi, Kumar studied printmaking and painting at the College of Art. He graduated with his MFA degree from the University of Tennessee in 2017. He is currently a Professor at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Since 2001, Kumar has been involved in numerous prestigious research projects, like “The Paintings of India” (a series of 26 documentary films on the painting tradition of India); “Handmade in India” (an encyclopedia on the handicraft traditions of India) and digital restorations of sixth century Buddhist mural paintings from the caves of Ajanta.

“As an artist, I am also particularly interested in the aspect of human intervention — the mark that a person leaves that alters a site, a history or the association to the object. I appropriate not just materials, but also the traditions. My work adds to a new meaning by sometimes destroying the object and sometimes defacing it, but in the end, nurturing it with a new invented narrative,” he says as he explains his art.

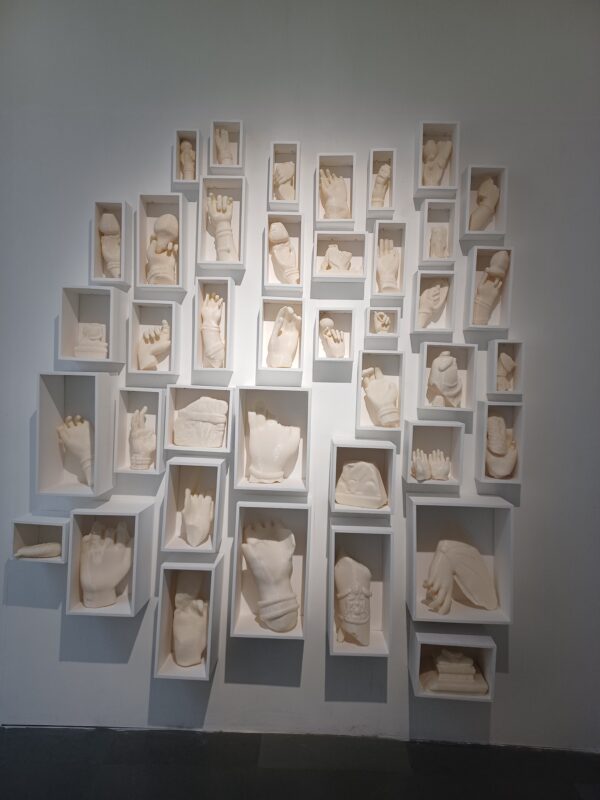

His work ‘The Case Of Broken Hands’ – which depicts the broken hands made of ABS (Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene) – explores the relationship between the object and its historical and social context. The work of art explores the questions: what happens after the temple walls have crumbled, the columns have been carted off to distant sites and the tombs have been emptied? What happens, in other words, after the material form is dissipated; the cultural artefact has vanished without a trace, or has been broken down, and transposed to a white cube museum or a mantle of a private collector?

Kumar’s work deals with memory, nostalgia and anticipation, and the meaning humans tend to derive from an object, and its absence.

Follow us on:

Instagram: instagram.com/thepatriot_in/

Twitter: twitter.com/Patriot_Delhi

Facebook: facebook.com/Thepatriotnewsindia