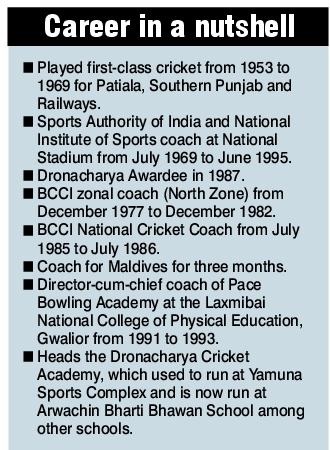

In November last year, during Delhi and District Cricket Association (DDCA)’s annual awards function, 87-year-old Gurcharan Singh was called upon stage to be felicitated.

Someone from the officials offered him a helping hand. He refused, and ascended the stage on his own.

“Wherever I am invited, people always offer their hand. I always tell them that I am fine for now, can do it on my own,” says the veteran cricket coach, who still spends seven days a week at his academy at a school in east Delhi.

Later this month, around the time of his 88th birthday, he will be awarded with the Padma Shri, among the top civilian awards in the country.

“To be honest, I never even expected to get it and never thought I would. It is an honour. People crave for it,” says Singh, who has been coaching for the last 54 years.

The careers of over a hundred first-class cricketers have been chiselled by his hands, including of 12 international cricketers — Surinder Khanna, Kirti Azad, Maninder Singh, Vivek Razdan, Murali Kartik, Ajay Jadeja, Gursharan Singh, Sunil Valson, Gagan Khoda, Nikhil Chopra, Rahul Sanghvi and Vijay Mehra (UAE).

But there is thirst for more.

Even today, at the Arwachin Bharti Bhawan School, he stands behind the nets and watches his wards play, sometimes reprimanding them for the unorthodox shots they indulge in.

“I always tell them, I can teach you cricketing shots, not others,” Singh says.

The day begins early for him at around 5.30-6 am. He walks at the Yamuna Sports Complex from 7 am to 8 am. Then at 8, he turns up at the school academy.

“I have 10 coaches under me. I prepare their kitbags for the day, select balls, ensure the nets are in order and set the place for the practice in evening. Then, at around 10, I go home, have a wash and take a nap. After a light meal in the afternoon, I am back at the nets at 3 pm and then oversee it till the end of the day before returning home, having dinner and going off to bed. I just eat three chapatis a day,” he narrates.

This has been Singh’s routine for years and he has been used to a harsh life since childhood.

Born in 1935 in Gandakas (a village 718 km from Delhi and now in Pakistan), Singh saw life take a treacherous turn very early. His father and paternal uncle, who would manufacture blankets in summers and then come to Amritsar to sell them in winters, were murdered before his own eyes during partition. Everything around him collapsed.

“I was too young to understand it, the hatred and politics around it. I was around 11-12. At that stage, you don’t understand much. You go where your family goes. My mother and sisters came to Patiala. I accompanied them.”

It, as he explains, brought him to the doorstep of cricket. He was first put in Singh Sabha School, a nursery for hockey players, and then in 1952, when he shifted to City High School as a class ninth student, he took up cricket.

His Ranji Trophy debut for Patiala came in 1953, against Delhi, under the captaincy of Maharaja Yadavindra Singh, the father of former Punjab chief minister Amarinder Singh.

“I had played Ranji Trophy in school itself. My college in Patiala (Mohindra College) used to give me Rs 130 a month just to play cricket. This ensured that my household expenses were taken care of,” the octogenarian recalls to Patriot.

Soon Singh earned the respect of Lala Amarnath and on the former India captain’s recommendation, was sent to the Rajkumari Amrit Kaur Coaching Scheme in 1958 in Mumbai under Kumar Duleepsinhji, a former England Test cricketer.

That very year, he joined the Indian Railways for a secure job, leaving Patiala and coming to Delhi in haste.

“People back home were already worried with my frequent travels. My sisters had got married and left the house and my mother was left alone with me. So, the solution recommended by others was for me to marry and have my wife give my mother company. I thought, ‘You have to get married sooner or later, why not now’. I couldn’t bring them along to Delhi, since I was to stay in a dormitory at the Karnail Singh Stadium,” he recollects.

“I used to live in dormitory along with other cricketers like William Ghosh. Other sportspersons also used to stay with us. I stayed at the stadium dorm for two-three years and then took a house in east Delhi’s Krishna Nagar in early 1960s, bringing my wife and mother.”

While playing for Railways and staying in Delhi, he earned coaching diploma from National Institute of Sports, Patiala.

While playing for Railways and staying in Delhi, he earned coaching diploma from National Institute of Sports, Patiala.

And then in 1969, bitten by the coaching bug, he left the Railways job and joined the National Institute of Sports (NIS), starting to coach at their academy at National Stadium in Delhi.

“I was posted in Delhi’s NIS in 1969. That was my first official coaching stint. The kids that used to play cricket back in the day, they faced great difficulties,” he recalls.

“There were no academies in Delhi. Only NIS used to be the academy. Clubs were there. There were 30-40 clubs at that time, some of them used to hold practice. The National Stadium academy used to attract kids largely from Delhi, and some from outside and there was huge demand,” he says further.

Things were very different then from nowadays. There are cricket academies in almost every corner of the Capital and even the National Capital Region (NCR) nowadays. Trainees turn up with the best cricket equipment and gear. The coaches charge well and don’t face paucity of equipment.

“I didn’t face those many problems since I was in Delhi. But coaches generally used to face big problems. Salary wasn’t much, residential facilities for coaches weren’t good, the balls were not of great quality. If there were good quality balls, they’d be limited and coaches wouldn’t get them. They would have to deviate from the straight and narrow. Sometimes, they would make a rich man’s kid play and make him donate balls for cricket. We had to do such things back then, which we don’t have to do nowadays,” he says.

Singh nurtured the NIS academy from 1969 till 1995. For a few years at the start, he would travel by bicycle, taking the old Yamuna Bridge to reach NIS from Krishna Nagar.

“When I joined, there was not even one turf pitch. When I retired, there were 22 turf pitches at the venue,” he says.

Famously, the venue was used by the Indian team for the camp to prepare for the 1987 World Cup. Many international teams on tours practiced there too, since the pitch and the ground he had prepared was very good.

Singh was also known to be a hard taskmaster and not known to budge.

Back then, Delhi’s top Test players would come to practice there.

“I remember a Test cricketer was batting at the nets. A left-arm pacer’s delivery hit him on the shoulder. The cricketer said ‘bas***d’ to the bowler. I ignored it. Then, after ending the nets, he hit the stumps in anger. I went up to him and politely told him to leave,” recollects the veteran coach, known lovingly in cricketing circles as Guchi Paaji.

“Years later, he returned as an MP and said he wanted to bat. I had expected an apology and a request but he didn’t utter anything. I told him, this isn’t a place for MPs. This is for kids.”

As he says about his insistence on discipline, “more than stressing on the technique, the coach’s job should be ensure that the player is regular, punctual and keen to learn.”

Singh also ensures that the kids get jobs and have a career.

As India cricket team’s national coach in the 1980s, he wrote a letter to the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) complaining about star batsman Sandeep Patil’s refusal to undergo fitness training session. Despite pressure, Gurcharan stuck to his stance.

Gurcharan would also take his NIS Club wards to the United Kingdom to expose them to foreign conditions.

When Kirti Azad, who was his trainee, turned up a bit late for one of academy’s tour matches in United Kingdom, Singh made Azad sit out.

“I still instil virtues of discipline among kids,” he says as he stands and watches kids run and climb the staircase, sometimes scolding anyone slackening.

He still plays 8-10 matches a year.

“I stopped playing for my club four years ago. But I still manage to play 8-10 matches. I last played in Gurgaon scoring 13 runs.”

Someone offered him help when he was running between the wickets and taking a single. But as usual, he refused to take it.