Kohli’s skillset may not include a sense of history, but he certainly shouldn’t maul history instead

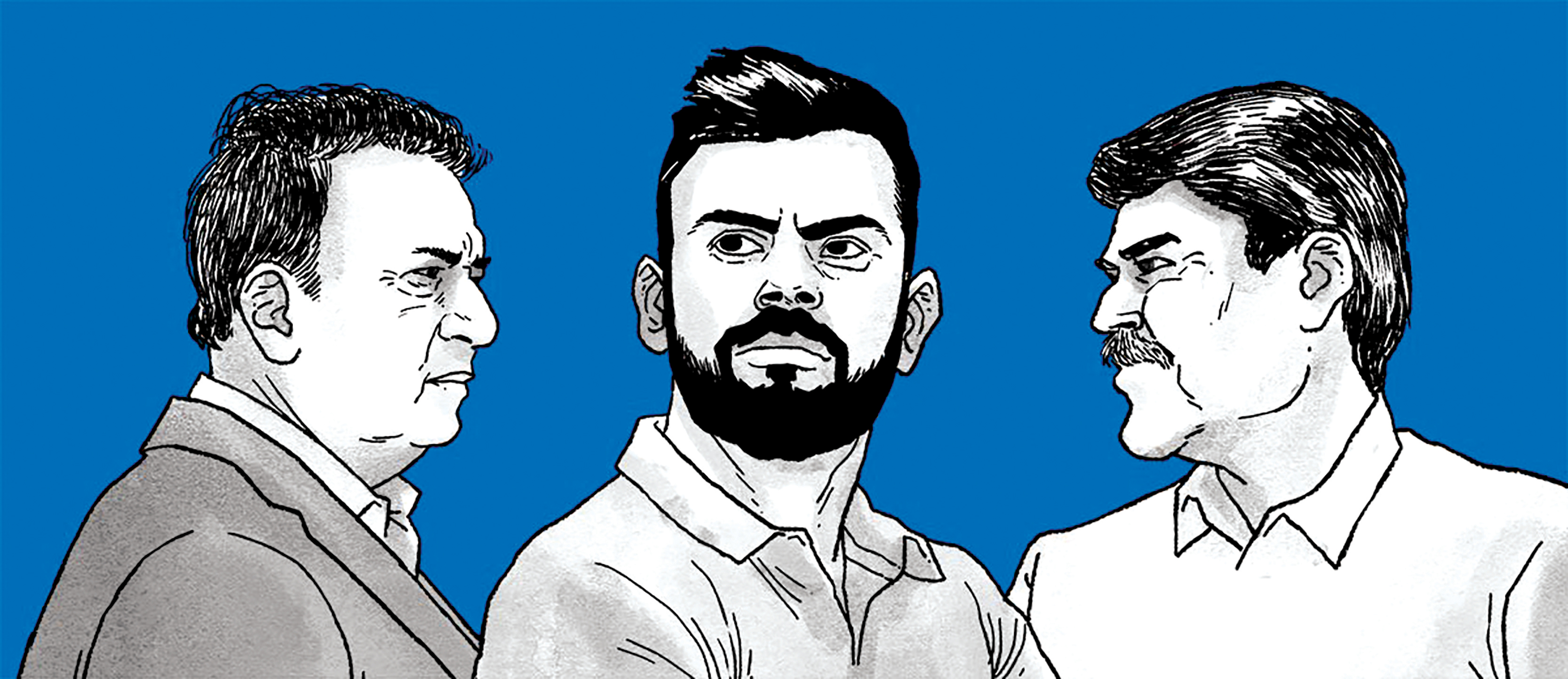

The historians of Indian cricket, especially those reflecting on the sociology of its changing demography, might not be able to defend Virat Kohli against charges of showing a lack of sense of history. Kohli had said India began to “stand up to tough Test challenges” during the era of Sourav Ganguly.

But 13 years ago, in a different setting, a different reason was offered to sympathise with a star Indian cricketer who was attacked for the same.

In early 2006, after his mammoth opening partnership with Rahul Dravid in the Lahore Test, Virendra Sehwag was clueless about who Vinoo Mankad and Pankaj Roy were — the legendary Indian opening pair of the Fifties, whose record the Indian duo nearly missed beating. Amid astonishment about Sehwag’s disconnect (or ignorance) with the legacy of the game in India, chroniclers of Indian cricket, including historian Ramachandra Guha, sought to understand Sehwag’s response in the context of his origins in Najafgarh, not steeped in cricketing folklore and located on the peripheries of what could be called metropolitan cricket centres in the country.

For instance, Guha saw the irrelevance of the game’s history and past heroes to a new breed of Indian cricketers as “perfect innocence” and a sign of their diversifying geographical profile — from major cities to the outskirts of smaller towns and the hinterland.

ESPN-Cricinfo had quoted Guha as saying: “Previously, cricketers came from the main centres and they were schooled in this knowledge of cricketing history and cricketing deeds, mainly statistical. Dravid in Karnataka was told about Viswanath, Tendulkar about Gavaskar and Gavaskar about Vijay Merchant. It is not so much in the case of the Sehwags and the Irfan Pathans…They play the game for its sake and nothing else.”

Such generalisations, however, run the risk of being falsified with different interests and personalities of cricketers coming from the same metro centres and cricketing milieu. Moreover, given Sehwag’s long association with the Delhi team and his locational proximity to the capital, the aspect that Guha could have explored was the interplay of Sehwag’s immediate social belonging and his approach to cricket.

Some former greats weren’t willing to conceal their disbelief though. In a piece for DNA, former Indian skipper MK Pataudi found the lack of awareness “disconcerting” and hoped it was a case of displaying “obscure humour”. Another former captain, Dilip Vengsarkar, called the episode “nothing short of shocking” and recalled the need to introduce a theory paper in the National Cricket Academy to impart a sense of history to budding cricketers.

In doing so, Vengsarkar talked about — as Mumbai cricketers still do — the city’s tradition of being aware of past greats. As the fabled Mumbai school of cricket slowly faded to pave the way for a more representative presence of different parts of the country in the Indian team, invoking it only suffers from generalisations similar to Guha’s observation. It also serves little purpose now, except for nostalgia.

Virat Kohli, however, can’t even take shelter in social analysis for what appeared to be his eagerness to allow the sense of occasion to take precedence over the sense of history. First, being from one of the old metropolitan centres of Indian cricket, cricket sociologists can’t resort to hackneyed geographical expansion-cricketing culture theories to explain Kohli’s indifference to, or amnesia about, pre-2000 Test wins secured by Indian cricket — in India and abroad. Second, unlike the explosive opening maverick image of Sehwag, the team captaincy entails a degree of cricketing statesmanship from Kohli.

What’s debatable, however, is whether historical awareness is a part of that.

As pointed out by Gavaskar, Kohli might have been swayed and played to the gallery in his post-match comments, especially in the city of recently-elected BCCI chief Sourav Ganguly. In an effort to be generous with his compliments for Ganguly, Kohli entered the hagiographical turf where historical facts don’t really matter.

It didn’t matter that Ajit Wadekar led the Indian team to a historical welcome after winning the Test series in England in 1971. Or a young Gavaskar spearheading India’s dogged fights — sometimes in winning causes — against the mighty Caribbeans in the 1970s and ’80s. Or the spin quartet weaving winning spells, or Kapil Dev’s memorable five-wicket haul to win the Melbourne Test and draw the Test series against the Aussies in 1981, or the 1986 emphatic series win in England under his captaincy. Besides memorable wins on foreign soil, the home Test victories kept coming, though with less frequency than what we see today.

But come did they, earned against quality Test-playing sides, equipped with world-beating attacks.

If Kohli’s tribute to the Ganguly era was more about crediting the latter for unleashing in the Indian team that abstract force called “killer instinct” or “world-beating will”, he sounds anachronistic. With the advent of Ganguly, which coincided with the beginning of this century, what was new was the visual expression of that will or confidence — a shorthand for body language in modern sporting encounters. It won its admirers for its point of departure from the more conventional ways in which the Indian team conducted itself.

That, however, isn’t to be confused with a longer journey that predated Ganguly’s years at the helm. As Gavaskar rightly pointed out, even in the 1970s-80s,Indian teams found ways to fight, win and draw Test matches now and then, and lose too in the process — sometimes comprehensively. Even the Ganguly-led period, statistically speaking, was a mixed one for Indian cricket. There were some memorable wins, some humbling losses, but no outright dominance.

However, the visual part of the resolve and mind games was more explicit in his era, furthered bolstered by two simultaneous developments. First, the Indian team trying to address the trust deficit in the wake of the match-fixing scandal. A morale-lifting figure in the form of a leader, aided by memorable wins against Australia in the home series early in his leadership stint (spring of 2001), played its own role in building that aura. Second, the visual aggression that he embodied was an ideal fit for the newly-arrived, and quickly proliferating, private news channels circuit in the country that was eager to latch on to his on-field show of purpose.

For a country that had grown up on the conservative conduct of its captains on the cricket field, Ganguly’s visual approach to leadership was as much a box office item for news shows as it was for photojournalists in the print.

Amid this embodiment of grit, what should still not fade away is the steely resolve of quieter times. Perhaps nobody represented it to a greater degree than the great Gavaskar himself. While his prowess and graceful courage against world-class pace attacks is well known, his last Test innings was a testimony to his fine and disciplined craft in playing spin bowling amid all odds. The vast reserves of mental strength that were in full display in his last outing in the park against Pakistan in Bangalore in 1987, despite India’s eventual loss, said a lot about his tough and resolute character. On a square turner of a track (“a mass of rubble impersonating a pitch”, to use Harsha Bhogle’s description of the vicious surface), Gavaskar’s last test knock of 96 will survive as much as a masterpiece of modern batsmanship as the gritty defiance of a quiet fighter in his last battle.

That was one of the many quieter battles in Test cricket that Indian cricket could very well be proud of fighting much before Sourav Ganguly arrived. A professional, or for that matter, a leader of a national cricket team, can’t be expected to have a sense of history as part of his skillset, but that doesn’t give him the licence to maul it.

In his autobiography No Spin released last year, the great Shane Warne looked back and talked about being inspired by the quality of cricket in the World Cricket Series of the Seventies. One wishes Kohli turned back a little more too — he could have found Indian teams fighting and winning much before 2000.

www.newslaundry.com