“While a company prices a perfume bottle for Rs 100, the same company will price a perfume bottle for women for Rs 200. The product stays the same, but the target audience changes. More specifically, the gender of the target audience changes which is why the product costs extra. And it’s not only perfume bottles, it’s the same with every other product that has a “for women” category. Be it shampoo, facewash, hygiene products, clothes, stationery items or anything else”, says Wabiz Bakhtiar, a marketing and business analyst.

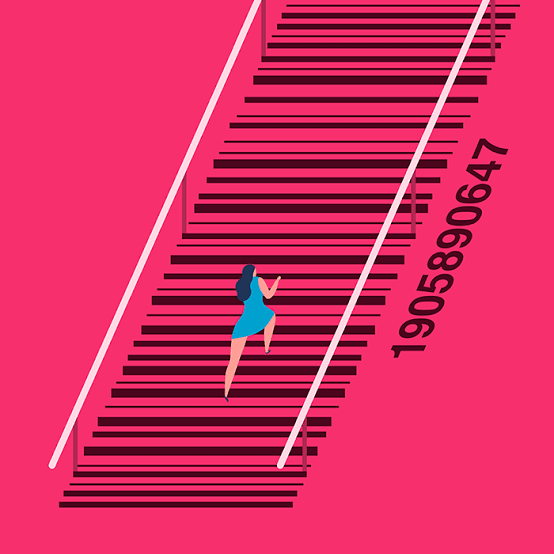

This gender-based pricing is commonly dubbed ‘pink tax’ where women pay an invisible price for products marketed specifically for them. “Most products are manufactured in pink colour — which is a ‘girl’s colour’ — and hence the term ‘pink tax’. It’s not a tax per se, but women do end up paying extra for the same product that men get in a non-pink colour”, explains Bakhtiar.

Most women are unaware of the premium they pay on a monthly basis. For example, the razor men use to shave is quite similar to the ones that women use for body hair. However, women’s razor is marketed as “extra smooth” and it comes in pink colour, thus making the product pricier than the razor men use. “It’s so blatantly marketed and sold, we don’t even stop to question it. We conducted a study to understand the difference in expenses that a man and woman of the same age make in a month. Our academic research showed that women end up spending 40-50% more money than men — irrespective of the age group”, says Shweta Bhat, a gender studies student at DU.

Her research also suggested that marketing experts tend to use this colourism and sexism to their advantage. She says that while a progressive section of society is trying to erase the sexist borders drawn with colours, the capitalists tend to use these borders for a measly average Rs 2 profit behind basic products like stationery – like fountain pen.

“This gender-based pricing exists through all ages and categories. For children, it’s the usual blue and pink for boys and girls respectively. A pencil for girls will cost more than a pencil for boys. For teenagers, a mobile phone cover is a good example. A sparkly or plain pink cover costs Rs 300 in Connaught Place, but a car or game-themed cover for boys will cost Rs 200. As you grow older, you see these prices in almost everything — especially hygiene products and clothes”, Bhatt adds.

The ‘pink tax’ has existed for several decades now. In western history, women had to pay extra to use public spaces and public facilities. A public show for women would cost much more than a general public show. Speaking about the dynamism of this ‘tax’ over the years, sociologist Kalindi Pandit says, “It is speculated by historians that this was done to limit the presence of women outside the four walls of her home. It was just another tactic to exert society’s dominance over women. However, as modernism grew, the social environment coupled with patriarchy brokered the pink tax that was applied to female consumers. Today, if women spend 50% of their income on “for women” products while men purchase only 30% on ‘normal’ products – and I am not even counting beauty products and essential feminine hygiene products in this — who do you think will have more financial stability in the long run?”

She further adds that women have always been under the societal pressure of presenting themselves in a certain way to get validation from society. “Society says we need to rid our hands and legs of natural body hair. So we pay for waxing. Society wants us to have clear skin and long hair so we invest in cosmetics. These aren’t things that women readily pay for. Tell a woman that she won’t have to visit anyone for a year or that she is free of societal expectations, and she will not go to a parlour to get her arms waxed for Rs 300. Men will say, ‘No one asked you to’ and then they are the ones to body shame a woman for not meeting societal expectations of beauty. We all live under this pressure, even when we try not to, and we also end up getting fooled by materialistic profit-gaining techniques”, says Neha Sikri, a women studies’ research student.

For a practice that finds its roots in sexism and patriarchy, ‘pink tax’ has survived conveniently in today’s materialistic sphere, without inviting questions about the divide it creates and the injustice it inflicts. Asha Joshi, a homemaker, was unaware of how women end up paying extra. When Patriot informed her about this phenomenon, she said, “Women already get paid lesser than men in all career fields. And now we pay more than men for basic products too? Who is giving us all this extra money?”

The term also covers the concept of ‘tampon tax’ where women pay taxes to the state for purchasing sanitary napkins, tampons, or menstrual cups. In India, women have been paying 12% GST for sanitary napkins since the raw material itself incurs a GST of 18% of 12%. Bhat says, “Are we choosing to have periods? They are a natural process. We would stop having periods if we could, but we can’t. So why do women have to pay GST for sanitary napkins? A mangalsutra does not incur any GST, but a pad does. Ironic, because people choose to get married, they don’t choose to have periods.”

Experts point out that the government can’t do much about ‘pink tax’ since it’s a consumerism phenomenon; however, the government can increase the budget for women and waive off the tampon tax. In Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s 2022 Union Budget speech, the word ‘women’ appeared only six times — foreshadowing the budget allocation for them. For example, the Gender Budget, which includes schemes for women across ministries, has shrunk for the fiscal year 2022-23. The Gender Budget has decreased from 0.71% of the GDP to 0.66%, according to an analysis of the All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA).

While the government cannot prevent overcharging, Bakhtiar suggests that awareness among women about how their gender is exploited for material profits can help eradicate the pink tax gradually. She says, “Currently, women aren’t even aware they pay more. Until they don’t realise this, businesses will continue taking the pink tax from them. Personally, I end up buying men’s perfumes, men’s shampoo, men’s razor blades because I know the products are the same as those marketed for women. But I only do this because I am not falling prey to the stigma — that a woman can’t use men’s products. You absolutely can. A little research on the products will tell you that. It’s time women start doing it to change the market standards and business notions.”

For more stories that cover the ongoings of Delhi NCR, follow us on:

Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/thepatriot_in/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/thePatriot_in

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Thepatriotnewsindia