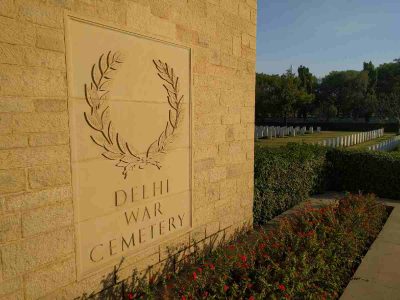

Leave behind the clamour of Dhaula Kuan, and the road towards Naraina grows quieter. Amid the trees and traffic signals near Brar Square, you might miss the modest gate that opens into the Delhi War Cemetery. But step inside, and the landscape shifts entirely.

The air stills. Lush green lawns stretch ahead, not with the casual grace of a park, but with solemn precision. Row upon row of headstones—each identical in height and spacing—mark the final resting place of young men who died in wars they didn’t start, in places far from home.

Here, surrounded by roses and neem trees, over 1,100 soldiers lie buried—most of them casualties of the First and Second World Wars.

Names, numbers, and the weight of loss

The marble markers are simple: a name, two dates, a regiment. J Taylor, 1925–1943. Maxwell Snow, 1924–1942. Chris David, 1919–1943. It goes on.

Almost all of them were barely out of their teens. Standing before these graves, it’s hard not to ask the inevitable: Did they deserve to die so young? The answer is always the same—of course not. And yet, here they rest.

A few tourists from Britain, Canada, or the US still find their way here. “This cemetery occasionally bustles with activity when a group of tourists arrives,” says a uniformed guard at the gate. “These groups usually consist of citizens from Britain, Canada, or America.”

Even Queen Elizabeth and then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher have made their way here.

The Indian absence

Indians, however, are rarely seen.

Perhaps the wars feel too distant, too tied to colonial memory. But today, Rahul and Neha, both students from Delhi University, are walking slowly among the graves, engaged in quiet conversation about the horrors of war. They are among the few.

The cemetery is maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), and though it is impeccably cared for, the space seems suspended in time—beautiful, but mostly forgotten.

You leave the cemetery with a knot in your chest. Gratitude, sorrow, pride, and something harder to name—a sense of the sheer scale of sacrifice, tucked into a corner of the city.

A sanctuary of the forgotten

The Delhi War Cemetery was created in 1951 to consolidate graves from across northern India. Sites in Kanpur, Dehra Dun, Lucknow, and Allahabad had grown difficult to maintain. The cemetery now houses 1,022 Commonwealth casualties from World War II, and 99 from World War I—relocated in 1966 from Nicholson Cemetery near Kashmere Gate.

Also Read: Delhi War Cemetery: Where the brave rest amid echoes of sacrifice

Its layout was designed by HJ Brown, a member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. Across its 10,000 square metres, two focal points stand out: the Stone of Remembrance, engraved with “Their Name Liveth For Evermore”, and the Cross of Sacrifice.

A side entrance allows wheelchair access. The main gate, though, remains locked on weekends and public holidays. Perhaps that, too, is a metaphor.

At India Gate, another kind of memory

Not far from here, at India Gate, a different war memorial rises.

The National War Memorial (Rashtriya Samar Smarak), inaugurated decades after independence, stands in quiet contrast to its colonial-era cousin. Where the Delhi War Cemetery speaks in silence and symmetry, the National War Memorial feels deliberate, symbolic.

The transition is immediate. Step into the circular expanse, and the bustle of Lutyens’ Delhi melts away. People lower their voices. Children pause. The air demands reverence.

“I have visited here with my family and friends more than two times,” says Sandeep Dwivedi, a media professional from Noida. “This entire place inspires you. When you read the names of martyrs of different wars inscribed here, you bow your head in reverence.”

For those who died after independence

India Gate honours soldiers of World War I and the Third Anglo-Afghan War. But the National War Memorial fills a long-standing absence—it honours soldiers who died in post-independence conflicts: 1947, 1962, 1965, 1971, Kargil, and beyond.

Its architecture is built around meaning. Four concentric circles mark the space.

At the centre stands the Amar Chakra, where the eternal flame—the Akhand Jyoti—burns, representing the spirit that never dies. Next is the Veerta Chakra, where six bronze murals depict famous battles fought by India’s armed forces.

But it is the Tyag Chakra—the circle of sacrifice—that grips the heart. Here, granite bricks are inscribed with the names of fallen soldiers. Walking its length is a visceral experience. The names seem endless.

Grief in granite

“Walking through the Tyag Chakra, reading the endless names etched onto the granite walls, is overwhelming,” the narrator reflects. “Each name represents a life cut short, a family bereaved, a story of courage and sacrifice.”

Sujata Sharma, a schoolteacher from Faridabad, says: “Seeing the names at Tyag Chakra, the eternal flame, and the depictions of bravery instils a profound sense of humility. You realise the immense debt owed to these individuals who fought, and died so that others could live in peace and security.”

Beyond the circles lies the Rakshak Chakra, and the Param Yodha Sthal, where bronze busts of the 21 recipients of the Param Vir Chakra stand watch.

And still, the question lingers

At the end of it all, both spaces—the cemetery and the memorial—lead you back to the same thought.

Names on marble. Stories we don’t fully know. Wars that still ask: was it worth it?