Over the past four years, Delhi’s summers have gone from merely hot to alarmingly oppressive. While actual air temperatures have remained high, it is the “feels like” temperature—or heat index—that has left the city’s residents reeling. This growing gap between recorded and perceived heat has become a hallmark of Delhi’s climate crisis, driven by humidity, shrinking green spaces, unchecked urbanisation, and climate change.

According to the India Meteorological Department (IMD), May and June in particular have seen a sharp rise in heat stress. In May 2021, Delhi recorded a maximum temperature of 41.2°C. However, the discomfort felt by residents was far greater, with the heat index touching 45°C. In June 2021, even though the temperature dropped slightly to 40.7°C, the oppressive heat persisted due to urban heat trapping, pollution, and high humidity.

A four-year trend of heat discomfort

The pattern continued into 2022. While May saw a dip in maximum temperatures to 39.5°C, the perceived temperature remained high at around 42°C due to increased solar radiation and reduced vegetation. In June 2022, actual temperatures fell further to 35.7°C, yet the heat index hovered near 38°C, amplified by unrelenting humidity and air pollution.

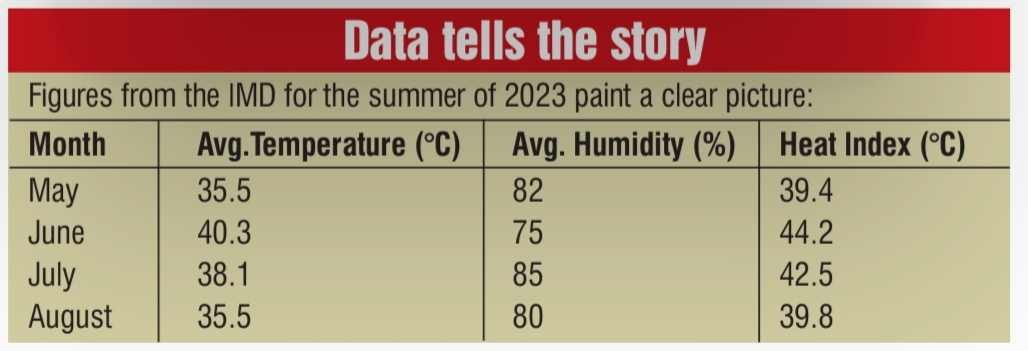

In 2023, air temperatures dropped again—May peaked at 35.8°C and June at 34.2°C. However, “feels like” values remained elevated at 39°C and 37°C, respectively, due to persistent construction, loss of green cover, and humidity.

The summer of 2024 marked a turning point. May saw temperatures spike to 41.4°C, with a heat index of 45°C. In June, Delhi broke records with a temperature of 41.95°C and a heat index of 46°C—the highest in recent years.

Why Delhi feels hotter than it is

Humidity plays a key role. When moisture in the air is high, the body struggles to cool itself via sweat evaporation.

“Sweat fails to evaporate effectively under humid conditions, causing the body to retain heat. That’s why even a 38°C day can feel like 45°C,” said Dr Meenakshi Pawar, Assistant Professor at Indira Gandhi Delhi Technical University for Women.

According to the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE), Delhi’s relative humidity increased by 8% between 2001 and 2023. This has contributed to a rise of over 3°C in perceived temperatures.

“But humidity isn’t the only culprit,” added Dr Pawar. “Delhi is a classic example of the urban heat island (UHI) effect. As vegetation and natural land are replaced by concrete, glass, and asphalt, the city becomes a massive heat sink. These materials absorb heat during the day and release it slowly at night, preventing the city from cooling down.”

She cited May 30, 2023, when central Delhi’s night-time temperature did not fall below 36°C. “Data from the People’s Archive of Rural India showed that areas like Delhi University and the Indira Gandhi Sports Complex were 3°C hotter than their greener suburban counterparts.”

Pushkar Pawar, a Delhi-based town planner, elaborated on the phenomenon: “Delhi frequently experiences a significant disparity between the actual air temperature and the temperature perceived by individuals—a phenomenon commonly referred to as the ‘feels like’ temperature or heat index.”

He explained that humidity has a compounding effect, particularly in the monsoon season. “High moisture levels inhibit the evaporation of sweat from the skin, the body’s primary cooling mechanism. When sweat cannot evaporate efficiently, the body retains more heat, causing the air to feel considerably warmer than the measured temperature. For example, an actual temperature of 38°C can feel as high as 45°C or more.”

Where the heat hits hardest

Densely populated areas, particularly in North-West and West Delhi, bear the brunt. These regions have sparse green cover and high concentrations of air conditioners expelling hot exhaust air.

“In neighbourhoods like Karol Bagh and Rajendra Place, which serve as hubs for IAS aspirants, office-goers, and students, single 100-square-yard buildings often house 40 to 50 air conditioners. This not only raises local temperatures but also strains the power grid,” said Pawar.

Also Read: Delhi Heatwave: Seven fruits, vegetables to consume during humid weather

He added, “Delhi’s infrastructure exacerbates this issue. Concrete and asphalt absorb large amounts of heat and release it slowly overnight. The UHI effect is further intensified by vehicular emissions, industrial activity, and extensive air conditioning use.”

Pawar also noted that many residential buildings are being converted into accommodations, significantly altering the urban layout and compounding the thermal stress.

Another factor, according to him, is wind speed. “During the hotter months, Delhi often experiences minimal air movement. Weak circulation fails to disperse heat from the body or environment. In densely built areas with narrow lanes, this effect is even more pronounced.”

Lack of greenery adds to the woes

Urban vegetation is crucial for regulating temperature. Trees not only provide shade and reduce solar radiation but also release moisture into the air.

“Trees are natural air conditioners,” said Dr Pawar. “Without them, people are exposed to direct solar radiation, dramatically increasing body surface temperatures.”

Satellite imagery confirms the growth of ‘heat islands’—urban pockets significantly hotter than their surroundings. Connaught Place, Lajpat Nagar, and central Delhi often record land surface temperatures 3–5°C higher than greener suburbs.

Despite moderate fluctuations in air temperature, high humidity and pollution ensured that perceived heat remained consistently high.

Residents feel the burn

For many, these harsh conditions are more than uncomfortable—they are life-threatening. On May 22, 2023, the IMD recorded 45.2°C, but the “feels like” temperature was 49.2°C. This posed serious health risks to the elderly, children, and those working outdoors.

“It feels hotter than when I was younger. I have to stop and rest often now,” said Ramesh Kumar, a 60-year-old commuter from North-West Delhi.

Medical professionals warn that extended exposure to such conditions may cause heat exhaustion, dehydration, and even heatstroke. Without awareness campaigns and support systems, vulnerable communities remain at high risk.

Medical professionals warn that extended exposure to such conditions may cause heat exhaustion, dehydration, and even heatstroke. Without awareness campaigns and support systems, vulnerable communities remain at high risk.

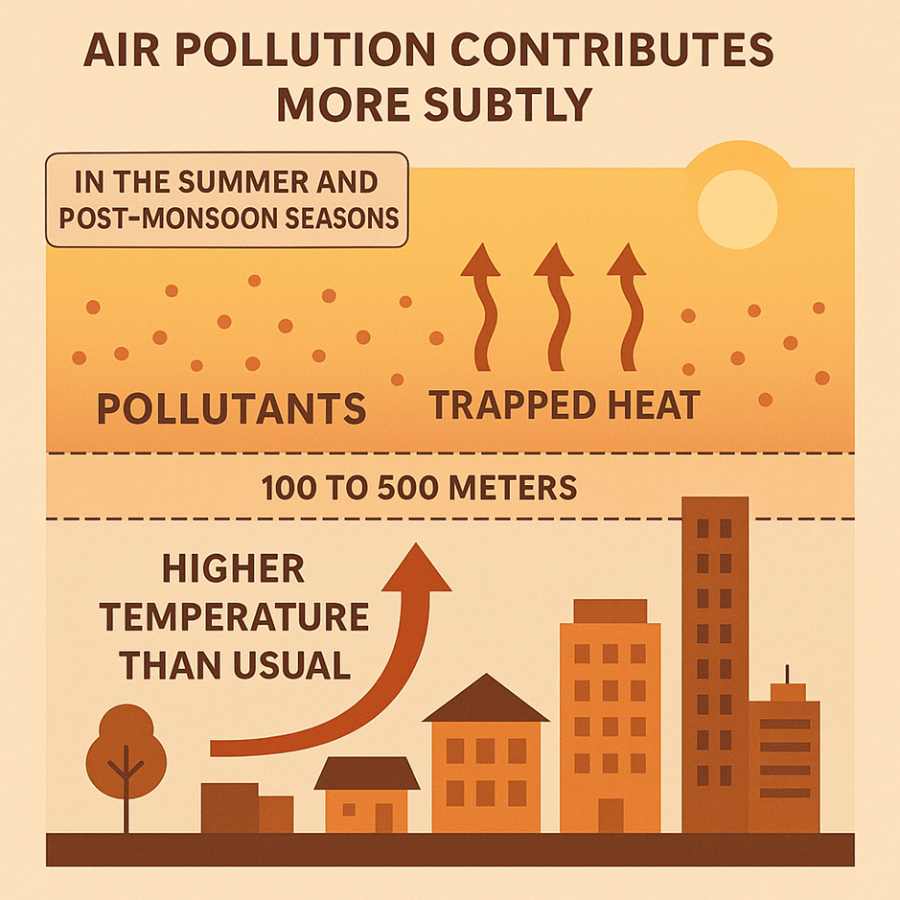

Pollution: A silent contributor

According to Pawar, air pollution also contributes subtly to thermal discomfort.

“In summer and post-monsoon seasons, pollutants get trapped in the lower atmosphere, between 100 to 500 metres. These particles trap and reradiate heat, raising surface temperatures. Combined with poor air quality, this adds to thermal stress and worsens daily life for Delhi’s residents,” he said.