Dastangoi, an ancient form of storytelling now much in vogue, uses words and gestures to engage, entice and entertain the audience

“Barbaad gulistan karne ko bas ek ullu kaafi thha,

Har shaakh pe ullu baitha hai, anjaam-e-gulistan kya hoga…”

(A garden can be ruined by a single owl, but what happens when there is an owl on every branch?)

This famous Urdu couplet, which profoundly depicts corruption, marks the beginning of a dastan (story). A satirical short story adapted from Harishankar Parsai’s ‘Nithalle ki Diary’, is being narrated in a small, cosy and picturesque art gallery near Delhi’s Siri Fort auditorium by performers of an art group ‘Chakor Lakeerein’. The audience is totally engrossed in this humorous depiction of reality. No glamorous sets, no background music, no dancing —devoid of all these embellishments, it manages to keep the audience engaged. Such is the power of words, such is the magic of storytelling.

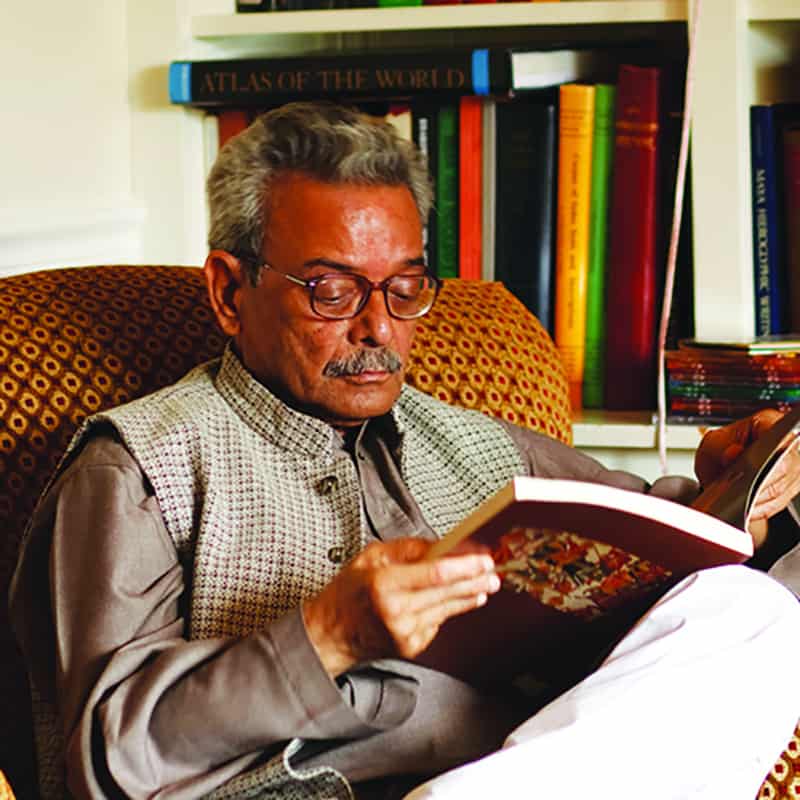

Dastangoi is an ancient art of storytelling. Though its origin has been debated, it is believed to originate from Persia in the 7th century CE. In India, particularly in Delhi, it gained popularity from the 16th century. But in 1928, with the death of the last dastango Mir Baqar Ali, the form died. It was Shamsur Rahman Farooqi, poet, theorist and Urdu critic, who infused new life in this art form.

In today’s digital age, this art of storytelling seems to die out. “How many teenagers today know the ancient epics Ramayan or Mahabharat? When our grandparents or parents used to recite mythological or other stories to us, it not only entertained us but educated us as well,” says Udit Yadav, 23, a dastango. He writes for a production house but has been pursuing theatre before joining ‘Chakor Lakereein’—a group which aims to restore unique art forms.

Such storytelling has immense impact on how a mind evolves, believes Wasi Zaidi, 26, a dastango by passion but software engineer by profession. “Exposure to storytelling at childhood improves one’s speech, knowledge and widens the sphere of one’s mind,” he says. When asked about its revival, he emphasised it’s more of a ‘reinvention’ by Shamsur Rahman Farooqi than revival. “From 2005 it (dastangoi) was presented to the audience. But the work to reinvent dastangoi began back in 1980 by him. Farooqi began collecting, assembling and writing dastangois,” adds Zaidi.

In ancient times, recitation of such dastaans took place even in the stairs of Jama Masjid. All they required was a story, a storyteller and an audience. “Unlike in theatre, no props or sound effects are used. Our setup is simple, without any embellishments. Because in dastangoi the main focus is on the story,” says Syed Khizar, 26, who’s into writing scripts for the performing arts. Like Zaidi, it was his passion which drove him into this. A software developer by profession, he believes one should be sure how much he wants to pursue an art before taking the plunge.

What sets dastangoi apart from other art forms is that it gives wings to your imagination. “In Dastangoi, words are supreme. Words have the power to conjure up images in your mind,” says Lokesh Jain, 50, theatre actor, director and writer. He was just 18 when he joined theatre. He explains how through variations in voice, through ada (mannerisms) and gestures, a dastango infuses life in a story and presents it to his audience.

Zaidi seconds this view. “In theatre or film, audience is bound to view what appears in the screen or stage. But in dastan, when we convey something, it conjures up different images in minds of different persons. Thus, each person creates their own imagery during dastaan. That is what is its uniqueness. Separates from a film or theatre,” he explains. He also believes that in dastangoi there’s no fourth wall. The story interacts directly with the audience. “We break that wall, it is as if we converse with the audience through our dastaan,” he adds.

To make the storytelling more relatable, dastangois are being narrated in Hindi as well. But Udit believes even if the audience doesn’t understand Urdu, the experience is still enjoyable. “Woh bas lafzon ka maaza lete hai. Aur unki khubsurati aisi hai ki unse ishq kar baith te hai” (they adore the beauty of Urdu words and fall in love with them), says Yadav. Jain believes ‘Urdu avaam ki zabaan hai’ (Urdu is the language of the common people). “I may be a Jain, but Urdu is my language as well.”

Contemporary themes and millennial topics are often the theme of today’s dastangoi. Also, the performers modify the flow, sequencing or portions make their presentation more engaging. Since the time of its revival, it has gained immense popularity.

But when it comes to pursuing dastango as a profession, there’s a long way to go. “Artistes are not given their due place in society, I feel,” says Jain. He further adds, “Ajkal toh kalakar banna matlab suraj ko aag dikhane ke barabar hai (Nowadays being an artist isn’t an easy task at all).” Zaidi, on the other hand, believes that ‘surviving’ on this profession depends upon the financial need, as well as the will to survive, of each person. Udit feels quality of work matters, if one wishes to gain success in this profession, “If you do good work, you will be noticed and surely gain recognition.”

Dastangoi is an art form which has indeed come a long way since its revival. To promote it further, the government must take initiatives. But dastangos are of the view that seldom does the government support such a unique art. “Government should encourage art,” says Yadav. He believes that some organisations do receive fund from the government, but they don’t make good use of it. “Different academies and committees are there who do receive funds from the government but those aren’t used for the mentioned purpose,” claims Khizar.

Jain believes that no matter in what field or profession you are in — be it engineer, doctor or something else — one needs to be aware of the life’s values, its principles and our society’s culture. And what better way than to use storytelling as a tool to serve the purpose. “We should engage our society with storytelling. And one should know that it has its importance in all fields, in all walks of life,” says Jain. “Warna toh sirf machine ban kar rahe jayenge, insaan na baan peyenge (Otherwise we’ll end up turning into mere machines and fail to be humans).”