What Hindi cinema said about the turbulent years of the Emergency, which shook up the Indian polity 43 years ago on June 25

On 25th June, the country will hauntingly recall the 43rd year since Indira Gandhi government declared the Emergency in 1975 to negate her disqualification from electoral politics for six years — a punishment pronounced by the Allahabad High Court for misusing official machinery during the elections. Her declaration set in motion a chain of events which marked a jittery phase for Indian democracy and civil rights.

What, however, it also fuelled was already volatile anti-establishment movements and underground mobilisation of youth unrest. Under state-ordained crackdown on citizens’ rights of, detention of leaders and political workers, there was also a ferment driven by angst.

Though bearing the brunt of censorship, the creative responses to political turmoil were also articulated. For that matter, the whole decade of the 70s was remarkable for the ways in which political agitation and disenchantment were finding creative expression and new idioms of discourse. To what extent did Hindi cinema, one of the few sites of popular culture for a large part in the country, reflecting the political currents of the times?

Going into the 1970s with a new star system and altered political landscape, Hindi mainstream cinema wasn’t keen to speak its political mind early in the decade. That was surprising given the seminal churnings the political life of the country was witnessing in the period.

The rise of Indira Gandhi as the new power centre, factionalism within the overarching Congress umbrella, the emergence of non-Congress political forces following the 1967 assembly elections in which the hegemonic status of the Congress suffered a setback. All that was also accompanied with a definite socialist thrust of the Indira government began with initiatives like the nationalisation of banks in 1969. Above all, what was intriguing was that the stuff tailor-made for the cinematic sense of the political, namely India’s moment of glory in clinching the convincing victory over Pakistan in December 1971 war, wasn’t chronicled on Hindi screen. That was ironic because a few years back Chetan Anand had made a landmark film even amid the gloom of defeat at the hands of the Chinese in the 1962 war.

While moments reaffirming India’s sense of territorial security and integrity were not captured cinematically, the context of sovereignty made a 1971 film in English too hot to handle for the Indian state. Satyajit Ray’s documentary Sikkim, made in English and commissioned by the Chogyal of Sikkim (the then ruler), was banned in 1975 when Sikkim became a part of India as its 22nd state.

Even in parallel Hindi cinema, which came of age in the 70s, such overt political films were not made. In hindsight, Hindi films have generally a long response time in addressing contemporary political events. In 1973, MS Sathyu’s Garam Hawa showed that, in being the lone cinematic exploration of the personal, social and political experiences of a Muslim family which opts to stay in India following Partition. Coming after 26 years of Partition, the film goes back to years in the immediate aftermath of Independence and Partition in 1947 to trace the journey of Salim Mirza from a sense of belonging to isolation, and then rediscovery of political engagement and common destiny that they share with the people of the country. Based on a story by Ismat Chughtai, the narrative was adopted for the screen by Kaifi Azmi and Abu Siwani.

One of the overrated political films of the period released in the year Emergency was Gulzar’s Aandhi (1975). Perhaps its popularity has been a beneficiary of inferred and publicised parallels between the protagonist, played by Suchitra Sen, and the life of Indira Gandhi. What also helped the political label to stick to the film was the fact that in a move to mitigate any negative perception, Indira Gandhi’s Emergency government banned it 26 weeks after its release, only to be re-released when the Janata Party-led government came to power in 1977. It was also shown on state-run Doordarshan.

In weaving a tale of a woman politician fighting her emotions to suppress the rekindling of the relationship with her estranged husband, played by Sanjeev Kumar, and the costs of a public life, Gulzar never managed to raise the film to anything beyond a stylised musical take on personal relations. The film was let down by a meandering script and Sen’s lacklustre performance while Sanjeev Kumar’s restrained acting and music saved the day.

If at all its ambition was to portray the leading political figure of the time, it failed. It had no insight into her politics or the nature of her regime. Its melodrama, hinged on three memorable numbers, wasn’t distinguishable from routine romantic tales. It had no insight into Indira’s politics or the nature of her regime. Its melodrama, hinged on three memorable numbers, wasn’t distinguishable from routine romantic tales. At most, it had a few moments of clichéd political satire, predictably about politicians wooing voters during an election campaign. That’s what this forgettable number “Salam kijiye janab aaye hain” from the film, the only one not talking about love, attempts.

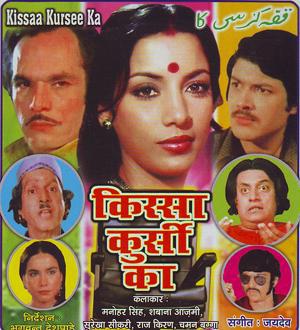

The most talked about political movie of the 70s, again a victim and beneficiary of ban alternatively, was made by then Member of Parliament and a little-known filmmaker Amrit Nahata. In a thinly disguised satire on Sanjay Gandhi and his acolytes’ whimsical approach to conducting affairs of the party and government, Kissa Kursi Ka was more of a visual collage of political cartoons that one found in newspapers before Emergency was declared on June 25, 1975.

It followed a narrative style, more suitable for theatre production, in lampooning easily identifiable figures of the

Sanjay cabal like Dhirendra Brahmachari, Indira Gandhi’s private secretary RK Dhawan and Rukhsana Sultana, besides Sanjay himself. The film’s trajectory through various institutions of clearance, ban and litigation is perhaps more riveting than the film itself. In a report published in India Today, issue dated June 15, 1977, Dilip Bobb writes:

“The prints were submitted in April 1975 for censorship clearance. Along came the Emergency and with it, Sanjay acolyte VC Shukla as I&B minister. The prints vanished and nothing more was heard till the Janata Party came to power and Nahata joined their ranks. The Supreme Court found Sanjay guilty of destroying the prints and sent him to jail for a month.

The case, like the petitioner, slid into obscurity thanks to a series of witnesses turning hostile.”

The film used the symbolism of a single person, played by Shabana Azmi as Janata, and the easily malleable-turned-ambitious politician Gangaram, played by National School of Drama (NSD) stalwart Manohar Singh, to see through the cobwebs of bureaucratic and political corruption, the façade of socialism, the absurdities of policymaking and the subversion of democratic processes. In a highly melodramatic scene in the film, quite in sync with the general tone of its narrative, the chair itself talks back to its new high-profile occupant to suggest what the time demands him from him to leverage most from the chair.

In art house cinema, the political themes embedded in persistent structures of exploitation, patriarchy and impoverishment kept finding expression in works of filmmakers like Shyam Benegal, Govind Nihalani and Mrinal Sen and Goutam Ghose. Benegal’s Nishant (1975) was a portrayal of the feudal origins of power relationships that were still shaping politics of rural India. With Naseeruddin Shah making an impressive debut, the film drew from the available talent pool of parallel cinema ranging from Girish Karnad to Smita Patil.

There is a popular argument that the angry man image that catapulted Amitabh Bachchan to undisputed stardom by the mid-1970s was rooted in the political messaging of anti-establishment in his films. Political scientists Suhas Palshikar and Yogendra Yadav, heading the team of NCERT textbook writing team for political science in 2006, have gone on to the extent of including Zanjeer (1973) as a film reflecting the political mood of the time.

Perhaps, they could have made a choice if Bachchan’s body of work in the 70s could be used for political material at all. What, however, is clear is that challenging and questioning of institutions of state power like police and judiciary could be seen as staple diet in the mainstream entertainers which shaped Bachchan’s popularity in the decade.

It was a clear point of departure from the respect and awe with which state authority was treated in the Hindi films of Nehruvian era. The themes of price rise, black marketeering, rampant corruption and the general anger against state authority provided the subtext to the emergence of popular rage which Bachchan was seen as articulating in covert plots of revenge sagas.

It is, however, anybody’s guess whether that was cinematic catharsis of the political rage of the ‘70s on Hindi screen. A few whispers and tangential voices talking about the political turmoil could be heard. That, however, didn’t compensate for any clear cinematic conversations about the politics of the day and its real movers and shakers.