This is the story of freelance foreign journalists who adopt India as their home and grow rich in experience

Delhi is one of the most difficult cities to live, perhaps, that’s what make it intense — and in some measure, engaging — to some free souls drifting across the globe. Like some of the freelance journalists from affluent parts of the world, where life is convenient, and therefore, less eventful, almost ennui.

Some of these freelance journalists make Delhi their home, and live here for years. Not only did it advance their careers as there’s growing interest in India, they became the India expert in their respective countries. Their stay has had profound impact on their personal lives as well.

Maria Tavernini, in her early thirties, is a journalist from the beautiful city of Naples in Italy. She has bohemian looks and a carefree attitude towards life. The ease with which she adapts to newer realities is exemplary. She likes to live in the hustle-bustle of noisy cities. Married to a photographer, a compatriot, they have made Delhi their adopted home, has a beautiful apartment in the congested locality of Kotla Mubarakpur in South Delhi. She has spent years in Delhi writing about India on a shoestring budget and has internalised its ethos; life in Delhi and has become an integral part of her own development process.

Tavernini has been living in Delhi “on and off since 2013.” She is not someone who experienced the shock of her life when she started living in Delhi. “I loved it (the experience) from the very first day. I felt an active, positive energy when in town,” she recollects with an air of nostalgia. She describes the “dark charm” of Delhi she’s fascinated with. For Maria the “inhuman” side of the city has offered some humane lessons of existence.

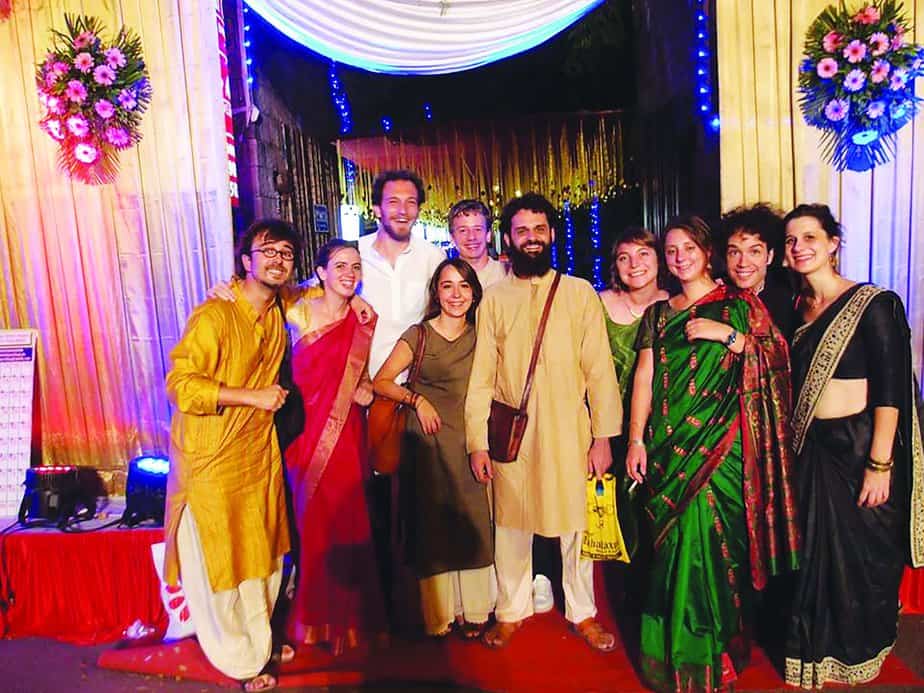

“As a freelance foreign journalist based in Delhi, I found a big, open-minded and variegated community of fellow reporters, both from India and abroad that have become to me the family-by-choice,” she says. Professionally, the stay in Delhi has been rewarding, for India offers varied situation, events and people to witness in day-today life.

But some were not so adaptable to the intense life in Delhi of a journalist. Freelancers are like lone warriors with little institutional support, which makes their task even trickier. Many of the freelancers interviewed by Patriot for this story retorted that their initial days in India were some sort of a cultural shock and it remains a mystery as to how they ended up living here for so long, for many years. They don’t want to be named, for they are either on a tourist visa or are not keen to antagonise the Indian establishment by being forthright about their views in public. Many of them are just here like foot soldiers, doing the difficult job of collecting information, to be editorialised in the newsrooms back home.

To the dismay of many of the freelancers, the stories that sell in the West, more often than not, are the ones that amplify prejudices and long held biases. There’s growing perception that Delhi is the rape capital of the world, and superstition guides lives of people, exploitation of the weak and underprivileged is institutionalised, that prevalent life in India is akin to that of the medieval times. Not all of this is true, they complain, some are frustrated as well, for they feel inadequate to correct the picture. The culture of the East is such a contrast from the prevalent culture ethos in the West that stories that do well, in most cases, only fan long-held biases.

Some of the interns with major news agencies, like this 28-year-old French girl who’s a cameraperson, explains her plight. She’s an intern who works like a full-time staffer on a tourist visa, and is paid less than half of a staffer. Despite this, her salary of an intern is much higher than the local support staff. The meagre salaries paid to interns is not just a visa violation, but also labour norms back home. It’s a win-win situation, for these news agencies, as semi-skilled young men and women, fresh out of a media school, learn to cover stories in alien conditions, sometimes fairly hostile, where language and culture are formidable barriers. But they profess their love for life in Delhi.

Matteo Miavaldi belongs to Rome. He is one of those freelancers who have over the years become experts on India in their country, not just about political issues but also socio-cultural milieus. He lives in Nizamuddin East with his Italian girlfriend, an Urdu scholar.

In his early thirties, Miavaldi moved to “the subcontinent” right after his bachelor’s degree. He started his stint in India from rural Bengal. “I was very young, full of energy and lucky enough to make rural West Bengal my entry point in the country,” he says. Miavaldi now speaks fluent Bengali. But his start here was “from the bottom.” It was a dreamlike scenario: he rented a house where monkeys were uninvited guests and they’d routinely snap the broadband cable, his link to the outside world. He participated in (as he describes them), “the wildest social gathering” under a huge banyan tree where locals would meet over a cup of steaming hot chai. To him, rural Bengal is representative of “real India.” India does still live in villages, though many Delhiites would find it difficult to reconcile with this fact.

Delhi happened after three years of stay in rural Bengal. It was more difficult for Miavaldi to adjust to life in Delhi after Bengal than Bengal after Rome. “Everything I thought I knew about India shattered into a thousand pieces. My Bengali became useless, life in the big city posed bigger and more complex questions,” he says. He was confronted with the glorious contradictions that Delhi as a city encompasses. As Miavaldi puts it, “a promising world superpower built on unacceptable inequalities. It felt increasingly incomplete, partial, and sometimes, even, insignificant.”

He met many people from varied backgrounds, travelled extensively, wrote many stories, also made some good friends. The realisation dawned, despite his extensive work for years, that he could only present a “microscopic glimpse of the gigantic diversity that’s the idea of India.” He contrasts the Indian experience with that of Borges’ Aleph, where one can observe the universe from every angle, simultaneously. He’s a big hit back in Italy amongst journalist friends, for “I am living the tough, adventurous journalist life that I always dreamed of,” he says.

He sports a long beard, like a sage, is a minimalist, loves to wear coloured cotton pajamas in summer, and spent seven intense years in India like a native. “India gave me some precious lessons: to be patient, humble, accept your limits and try to be faithful, as far as possible, to experiences that come your way.”

Predictably, when they go back home, they start to miss India two weeks later. Last heard, Tavernini is trying to run an eatery in Naples, before she comes back to India —she’s not sure when, but for sure she will.