The virtual courts have real and far-reaching implications in the administration of justice. Here’s why

One of the impacts of the pandemic has been that it has precipitated the infusion of technology in the administration of justice. Urgent matters are now being dealt with digitally in what’s called electronic courts or e-courts, where the judges, lawyers, and various stakeholders are connected electronically but are not present in the same physical space.

This was an ongoing process and the Supreme Court has been encouraging and supportive in the past, but the lockdown has “hastened the process by ten years,” says Vikrant Singh Negi, a senior lawyer, who did his Master’s in law from Duke University in the US, “Infusion of the technology in judicial processes is the need-of-the hour.”

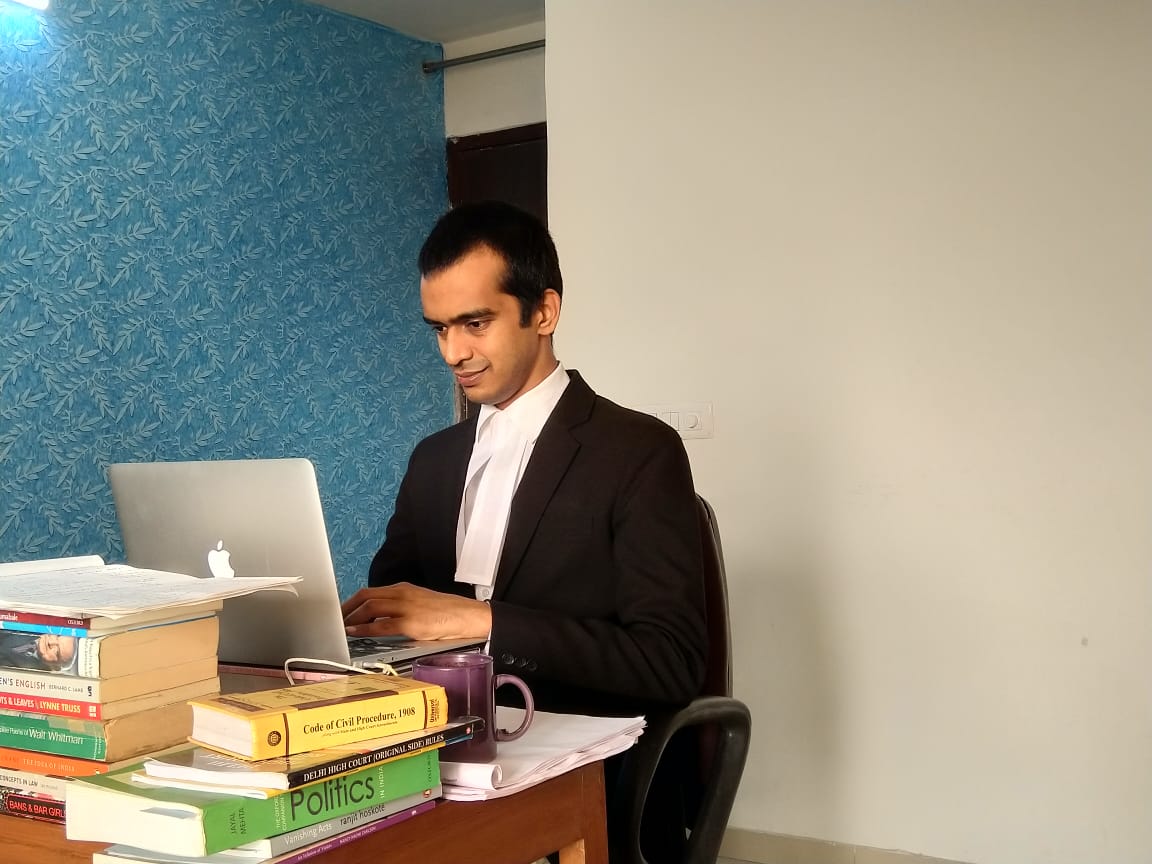

Delhi High Court is the leader in this direction, and many judges insist on filing the cases digitally. Naveen Nagarjuna, a young lawyer, who actively deals with online cases these days, informs that the Supreme Court has issued an order detailing the guidelines ‘for the court functioning through video conferencing during Covid-19 pandemic.’ Also, the Delhi HC has issued a notification in this regard.

Other higher courts are open to going digital but for that to happen there’s a need for substantive investment. Pointing to the institutional habits, conventions and practices, Negi says, “A huge barrier has to be overcome–that’s both psychological and physical.” In the latter case, Negi stresses, the government will have to allocate sufficient funds to increase the capacity of the broadband to ensure an integrated functioning, and most importantly, a secured system at all levels.

“The pandemic has given a sense of urgency to the whole process,” he adds. Negi feels that the open court system has its own merits when it comes to criminal matters. “Body language is very critical.” It’s not just important what is being said, but how it’s being said, to arrive at a conclusion. Agrees Nagarjuna, to access the “demeanour of the witness is important.”

In terms of advocacy, there’s a need for some adjustment as well. Much like in the West, “we have to prepare everything beforehand. And I’m supposed to share all the case laws and other details with the other party in advance. I can’t use anything new,” Negi clarifies, “though in some cases we share the screenshots of the documents if not intimated about it in advance.”

The preparation for online courts is cumbersome, which is actually not a bad thing, but the whole process is fairly tedious for the judges. There are many frames on the screen, and sometimes it is difficult to figure out who’s talking; to keep staring at the screen can get very cumbersome and tiring, and the whole process is fairly demanding. Further, it takes time to adapt to a new system. Nagarjuna is empathetic, “It’s stressful for the judges to stare at the screen for hours together on a day to day basis.”

But thankfully, judges have a tool that makes things easy. They can mute an argumentative lawyer and can ensure that no one speaks out of the turn and at the same time. “The judges can mute the mike of lawyers who are interruptive,” says Nagarjuna, “so even soft-spoken people have a chance to be heard,” he adds with a smile.

Shradha Narayan is a young lawyer, 30, has been practising for five years, and feels that there’s no substitute for open court proceedings where she learned a lot seeing seasoned lawyers argue a case. “It’s always a learning experience for me,” she says. Still, she’s mindful of the fact that change, in light of technology, is inevitable as computers have revolutionised, like any other field, how the law is practised.

The digitisation of court records–an ongoing project–has facilitated the dispensation of justice. Narayana explains how there’s a movement all over the world towards paperless courts, which are better organised: papers don’t go missing and filing becomes easier with everything online.

Way back in 2014, Shradha recollects, “When I was just out of the law college, I remember justice (Supreme Court) B Lokur talking about the potential of e-courts in dealing with the pendency of cases, and that ‘it is high time the obsolete and outdated systems are done away with,’ if I remember correctly.”

She feels e-courts are here and the only question remains is how best to employ technology to make the administration of justice more efficient to deal with some core problems. Say, for instance, the pendency of cases. There are 43.55 lakh cases pending in the high courts and out of these, 18.75 lakh relates to civil matters and 12.15 lakh are criminal cases. As of June 1, last year, 58,669 cases were pending in the Supreme Court.

Nagarjuna is of the view that though the infusion of technology is good, it has its own limitations, particularly when it comes to dealing with the backlog of cases or for that matter lakhs of undertrials languishing in jail.

“Not much hope as of now,” says Nagarjuna, as these issues are not technology-specific but relate to “the inaccessibility of legal aid.” Negi says technology will be effective only if the laws governing bail are “radically changed”. Further, that it’s “abhorrent that people are behind bars for weeks and months, even years, merely because the chargesheet is not filed.”

It’s ironic that taking pictures is prohibited inside the court, though anything filed or discussed in court is deemed to be in the public domain. “Transparency facilitated by technology is a step forward,” says Negi. People can now access proceedings in Delhi HC after registering online. Something that happened in the West long back.

For instance, in the US, the court proceedings are orally recorded since the mid-1950s, and transcripts made public. With the coming of the Internet, all of it is available online for anyone to hear. It’s possible to witness stalwarts arguing a historic case that by its sheer impact changed the course of history.

Negi feels it’s a double-edged sword, there are advantages and challenges as well. “There’d be many celebrity lawyers, who’ll put up a spirited show, a lot of theatrics, knowing that their audiences are beyond the confines of the courtroom.” He feels it’s imperative for the better use of technology that verbosity by lawyers is checked, they are better prepared and stick to the time frame allotted to make their point. At best, the mute button at the disposal of a judge has a limited application. But if Parliament is any indication, live telecast, many would argue, hasn’t improved the levels of discourse.

All said and done, justice will not only be delivered, but thanks to technology, will be–literally–seen to be delivered.

(Cover: Naveen Nagarjuna deals with online cases)