Girls in the capital city still struggle to get education beyond 8th grade, yet less than 13% of the Centre’s scheme to promote education of the girl child was used

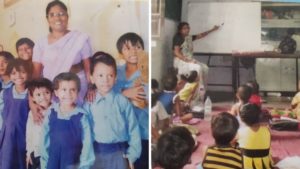

When Maya saw the status of girls’ education in her neighbourhood in South Delhi’s Jasola, she decided to take matters into her own hands. She grabbed a rug and laid it outside her home to teach her three daughters so that others could join too.

Her efforts led her to join the National Service Scheme with Jamia Millia Islamia, which then saw her teach 30 children from Classes 1 to 5.

This effort began in 2000, and two decades later she still plays a part in helping girls become self-reliant. Her three daughters are now grown up, with hard-earned Master’s degrees. And while she agrees the city is much better off than before in this regard, Maya says there is still a long way to achieve equality for the girl child in education.

“The key is to change the mindset, especially of mothers. Men may be even persuaded to change their minds, but I don’t know why the mothers think ‘What is the point of teaching the daughter?’ They will pay for their sons’ education but when it comes to girls, they have a problem. Which is why you will see many girls who have studied only till 8th Class, as their education is free under the Right to Education Act”.

In fact, the ‘Household Social Consumption: Education in India’ as part of 75th round of National Sample Survey’ shows that in Delhi – the highest level of completed education secondary and above – among persons of age 15 years, the percentage of male educated persons is at 69.3% whereas females are at 56.9%.

We can also see this gap in equal opportunities through the ‘Age Specific Attendance Ratio (ASAR)’ which shows how the percentage of girls in both rural and urban settings of Delhi do not follow through with their higher education.

In the early stages while females are more, this changes around the age of puberty. There were 45.5% males between the ages of 3-5 years going to school compared to 50.8% females of the same age group. Then in the ages of 6-10 years, males were at 99.7% while females were at 98.1%, this became much lower by the age of 11-13 at 83.1 while for the same age group males percentage was at 96%. In the next age group, while the female numbers increased to 89.7%, it was still lower than males in the same age group of 14-17 years at 90.9%.

What is interesting is that those girls who did make it to this level of education, went on to study higher, as between the ages of 18-23 years there were 28.7% males shown whereas females were at 35.6%.

The Central Government in 2015 amid much fanfare had launched the Beti Bachao-Beti Padhao (BBBP) scheme to promote awareness regarding girl’s education and combat the declining Child Sex Ratio (CSR), but the ground reality such as this speaks of the inability of the scheme to have changed people’s mindset.

Then there’s Minister of Women and Child Development Smriti Irani’s answer to questions on the BBBP scheme in the current session of the Lok Sabha, which shows the underutilisation of funds being a consistent occurrence.

One sees a lacklustre programme which while pumped with money has no takers; NGOs working with promoting and also providing education to girls calling BBBP’s advertisements as having no substance.

Delhi in 2019-20 had Rs 2.3 crore funding available, out of which it utilised a tiny fraction at Rs 27.57 lakh. While this has been the case over the years, this term’s underutilisation itself is significantly higher. Even looking at the neighbouring state of Uttar Pradesh where concerns of low sex ratio and violence against women is high, the use of funding was abysmally low at Rs 9 crore out of the allocated Rs 17 crore — money which could have been used for qualitative action against violence and educating girls.

The founder of SAKSHI – an NGO working for the education of the underprivileged where Maya now works, teaching girls how to sew – Dr Mridula Tandon says working in marginalised areas in Delhi has shown that “even today for a woman to cross the threshold of their home she needs to be accompanied by a male member of the family”.

“We have discovered that they wouldn’t want the girls to study and the girls had this great urge to learn”. She tells us about the year 2004 when her organisation first started their work in Shaheen Bagh. “We managed to convince the communities to send us girls to give them value-based education. We took a group for computer education and out of them two girls passed, one got a job with Tech Mahindra and another with Vodafone.”

Tandon says, “When a 10th class pass with computer training got a job paying them Rs 8,000 back in 2004 – in a family with 10 members where the average income in the family did not exceed Rs 10,000-15,000 – it was a mind-blowing statement to the community that a woman could earn and actually sustain a family. The next day we had lines outside our centre with families who wanted their daughters taught.”

Looking at the National Sample Survey data quoted above, it also gives us the percentage of persons of age 5 years and above with the ability to operate computers. Through this again we see the imbalance of opportunity with 47.3% males in Delhi’s rural plus urban areas able to operate computers, whereas females were at just 37.2%. At the same time, for internet usage ability there were 55.5% males who knew how to as compared to 44.2% females.

And while Tandon says there have been many positive changes, families still hesitate or refuse to teach their daughter beyond class 8. “First factor is parents don’t value education beyond Class 8 because they are hoping that during harvest season they will go to the village and marry her (the daughter) off. Second is safety and security and then the added bonus is that if the child is home then the mother is free to do other things and step out and get some gainful employment; lastly, the child herself may not be interested.”

She also points to the girl child reaching puberty and not having access to clean, secure toilets as one of the reasons behind girls dropping out at that age. The Kishori Yojna, a flagship programme to provide free napkins to children studying in Classes 6-12 has been implemented. In December last year, the Delhi High Court had asked the AAP-led Delhi government and the municipal bodies to keep providing sanitary pads free of cost to school-going girls as also to those who have dropped out and continue with their awareness programmes and schemes for promoting menstrual hygiene.

Now, this July, the Delhi government has also decided to install sanitary napkin incinerators (SNI) in 3,204 toilet blocks of 553 girls and co-ed schools under the Directorate of Education (DoE) and the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD) to combat the taboo on menstrual hygiene.

But as Tandon and Maya point out, the mindset that a daughter’s education contributes nothing to the family’s well-being is one that has still to be countered aggressively in the Capital city. One of the programmes that the NGO Sakshi runs is to assist a girl child’s education from Classes 8 to 10, assisting them with a social worker and a stipend “so that parents don’t have to think about their expenditure for their uniforms, books; we teach them about the beneficiary schemes given by the government, we teach them about health so it sustains a future family with much greater power than if they had dropped out in 8th grade…NGOs like ours show that a girl child can get education and be turned into a contributing member of the family.”

Now during the pandemic, the problem is even greater with children being asked to study through online classes, which many families living hand to mouth, cannot access.