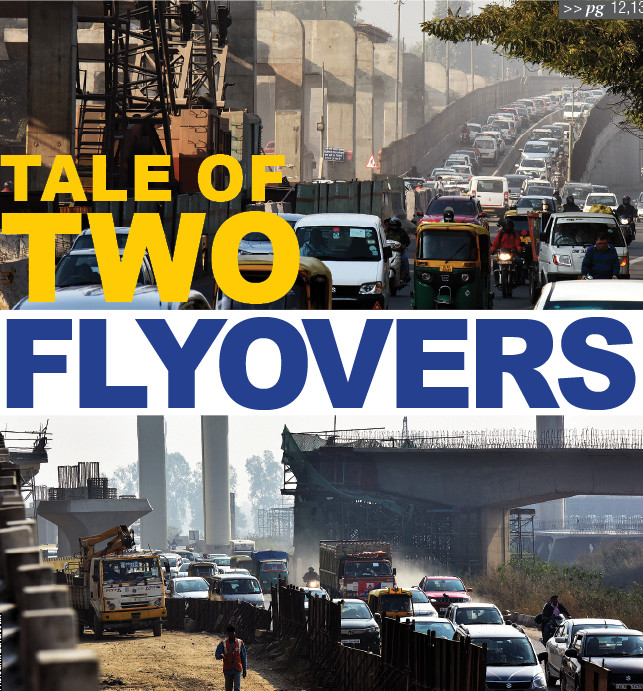

The tale of two flyovers tells you in a nutshell why traffic bottlenecks occur and what lack of planning is doing to make driving around the city such a nightmare

On a bright winter Sunday, you may feel the warm sun beckoning you. It seems to say: Take your car out and enjoy my glory even more. Surely, there would be little traffic on a holiday.

But not in Delhi. Especially not if you plan to drive from South Delhi to Gurgaon or vice versa, through the mess that is the Rao Tula Ram Marg flyover. The beautiful sunny day soon becomes a sweaty anger-spewing, abuse-hurling one. And this is the road that connects South Delhi to the airport, which should have a smooth hassle free ride.

The bottleneck you encounter on the Outer Ring Road came up in 2010. Soon after the two-lane one-way flyover became operational, authorities realised that it would not work. So then they made it one lane on either side. This is ridiculous for Delhi, as it expects drivers to stick to their lanes. So everyone is on edge, waiting for a chance to push their bonnet in before the other.

And despite in 2014, another three-lane flyover parallel to the existing one being sanctioned, the stretch gives a nagging headache to anyone negotiating it — far from what the purpose of the said flyover was to be.

Uber driver Ram says under-construction flyovers are perpetually upsetting his schedules. “A route which would take 15 minutes, takes an hour and half. It’s not just time that is getting wasted but also money and energy”.

He also points to a junction from Uttam Nagar to Dwarka Mor. “It’s so bad that if I get a booking for that route I cancel it. I don’t want to be stuck in that situation”.

A little bypass from under the flyover takes you to Dabri if you want to go towards Dwarka but only one car can pass at a time. It is a traffic nightmare.

“It gets worse because of the thela and richskaw walas who are just allowed to stand anywhere, blocking the narrow roads”. Even on the Mahipalpur road, the situation is grim, he says.

Ram believes this goes on because politicians don’t care. “Roads are blocked for the Prime Minister to pass. The MPs have huge homes which they don’t even need to leave because they get everything at their doorstep. When they have to go out, it’s to Parliament, or to the airport. Even if they have to shop, they’ll go to the nicer places where there is no heavy traffic, or potholed roads”.

“The areas they live in, they don’t know what common people go through. And some of the netas who come from small towns, they haven’t even seen roads, so for them this is great improvement”, Ram adds.

For the most part, knee-jerk reaction to the city’s needs — like the Rao Tula Ram Marg fiasco —mean commuting hell. In September, a report claimed that more than 20 months after it was supposed to be finished, only 55% work has been completed. Deadlines for the three-lane parallel flyover have been missed four times already, and the December deadline has shifted to March 2019.

Causes of delays have ranged from “funds constraint” and opposition by residents — and judging by the area, some wealthy, influential ones. The problems have caused the pocket of the Public Works Department (PWD) to be further dented, with one report quoting an official as saying the cost of flyover had risen to Rs 330 crore.

The other elephant

Another major road that has been facing constant delays is the Barapullah project. Divided into three stretches, Phase I connecting Sarai Kale Khan and Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium became operational for the 2010 Commonwealth Games. After that, it has seen a steady trickle of delays, having missed three deadlines. Phase II, connecting Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium to INA market, became functional only in July 2018.

Part of the Phase III project is stalled due to ban on construction due to the pollution levels in Delhi. It will be opened in the first week of January, according to a PWD official.

But in this phase, the problem that eludes solution anytime soon is of land acquisition. The PWD official, who does not wish to be named, said that despite several hurdles previously, the biggest one which remains is of land acquisition. “This has been going on for two years. A stretch of 750m comes under the DM South East. This is hindering the work”.

When asked whether land acquisition was not something deliberated before the work began, the official cited that “UTIPECH (Unified Traffic Transportation Infrastructure (Planning and Engineering) Centre) had given its approval. Even the DDA had given an NOC (No objection certificate). Only later did it become known that the 750m patch of land in the corridor came under private ownership”.

“If land acquisition is fast-tracked, then things would go smoothly. It’s not rocket science. But because of the acquisition, things are at a standstill,” he maintains. And even if negotiations go through and the land is acquired, it would take them a further 18 months, he says, to complete the project.

Which means it will not be until 2020 when connectivity will be achived. Till then, the much talked about loop will not be helping the innumerable number of people who travel back and forth during peak hours for work.

When you go past the site, you can see that a lot of work is yet to be done before that can be achieved. A worker at the stretch of the flyover being constructed said they work from 8:30 am to 8:30 at night, so long hours are being put in.

To get a perspective on the state of Delhi’s flyovers, Patriot spoke to School of Planning and Architecture’s head of department of transport planning, Dr Sanjay Gupta. He believes that one of the main reasons why Delhi faces such kneejerk reactions is because transport facilities are not built foreseeing future demand. He also blames the lack of trained planners even at local bodies. With “Delhi having a weak coordination system”, problems

worsen. “We need a Unified Metropolitan Authority (UMTA) which would look into all means of transport in the capital and make its integration a cohesive enterprise”.

Instead what the country has is a “policy vacuum in the Centre.” With “no Delhi transport policy either at the state level, there’s no plan as to how we will take the city forward”, which takes into account the growing population and the stagnating space. What prevails is “constant firefighting”.

And while the institute churns out students with the knowledge of how to tackle the problems that Delhi faces, and to build something viable for the future, Gupta says there aren’t any government jobs available to them.

Thus, the responsibility vests with the government to equip itself with enough means to be able to accommodate the massive population growth and where travel time of 20 km does not take two hours — on a good day at peak hours.

Future planners speak

‘We need smart software’

Vinay Kumar, 2nd year student of Transport planning, SPA

What I have observed in Delhi, is that while there are flyovers and some well-built roads, the traffic management is a huge problem. And then once constructed, flyovers are not maintained.

In case there are pot holes, they are not fixed. This affects the travel time and furthers the traffic congestion. I think management should be the first part to controlling traffic and quick response techniques to improving the roads.

Take for example the smart cameras in London, UK which use new age software to control traffic. They can predict from the first 60 minutes what will happen in a particular area in the next 60 minutes.

In other countries, software detects potholes and sends the message to the respective departments. Once these departments receive the messages they must resolve the problem within 1-2 days. If it’s a case of an accident, the system immediately informs the ambulance service and well as the police department as well as the municipal department. All of which is expected to lead to a quick response.

In India, we have no such thing. Instead when we have to forecast for the future, our base data is taken as the Census. The last one was in 2011. So how can this possibly be accurate to guage future demands when we can’t even project for the present?

‘Attitudes have to change’

Sowmya, 2nd year student of Transport planning, SPA

The major problem with Delhi is its vehicle ownership. Even though people have been provided with alternative transport, they still prefer their own vehicles.

Thus, to cap these vehicles the government must come up with some measures. Singapore has a great model whereby it caps the number of vehicles plying on its roads. To own a car in Singapore, you need a certificate of entitlement from the Singapore government. The supply is limited, and certificates are distributed by auction.

It is also so expensive to register the car that people don’t end up buying them.

At the same time, while curbing private vehicles, the government must also holistically look at making the public transport system better. A whole city can’t be sustained by a single system like the Metro Rail. As the city’s population increases, the modes of transport should keep changing and increasing in number.

So, for a better future, it must start shifting more towards the rail system. The normal railways as well. Plus, as we want the user base of private vehicles to shift to public transport we must think about what we will provide that will make them shift.

Even the increase in Metro fares really affected the number of people using the facility and they went back on the roads. You must be able to forecast for the future. Not only consider the regular growth rate but also monitor your policies.

‘People must use public transport’

Sonali, 2nd year student of Transport planning, SPA

Yes, the roads are bad, yes there’s traffic, but one of the first and foremost things that a policy maker must deal with is user behaviour in Delhi.

People think taking public transport is not the best thing. When I joined college, my parents said they’ll buy another car for me. But I prefer public transport.

The citizens who really need public transport find it too expensive, and the ones who are well off don’t want to use it. For the class pf people who don’t want to forgo their comfort, there can be a separate coach like a chair car. This will facilitate a shift for those travelling by car to take public transport.

If user behaviour does not change, then the scenario on the road won’t change either.

Congestion occurs because of behaviour. It’s utter chaos. It takes minimum 1 hour to come from Mehrauli to ITO on the bus, if I travel early at 7 am then it would take me 30 minutes. The point is that if all 50 of those sitting on the bus decide to use their private vehicle, then the situation in Delhi would go from bad to worse.

‘Demand management is needed’

Jagannath Das, 2nd year student of Transport Planning, SPA in Delhi, the high vehicle density means the space capacity becomes lower. People think that adding a flyover would ease the road conditions. But what it does is supply people with the means to get their cars out. So I think planning should be oriented towards demand management.

Construction of flyovers is undertaken to ease out congestion, instead it spreads it out. From Nizamuddin station to ITO, the flyover is there to ease out the traffic which goes towards Meerut and Ghaziabad and it takes that congestion near the Mata Mandir Road. So, the links are also creating problems.

Policymaking has to take into account the demand. There are lots of cities that are dealing with demand management to make public transport stronger.

Furthermore, in Delhi, the situation is different from other cities. Everything is segregated in such a manner, with schools in separate locations from homes, to offices and shopping centres, that people are constantly on the move. So, there’s a constant need for travel.

The planning must thus, look into demand management and create areas that are self-reliant.

‘Agencies must coordinate’

Gurunathan Karthik, finished his bachelors in Planning from School of Planning and Architecture (SPA) Delhi in 2016. His thesis on ‘Smart Master-Planning Process’, looked at the gaps and issues with the current process of master planning in New Delhi.

He is currently an independent consultant in Rural Development. He shares his view on the inordinate problems that hinders fruitful planning, and the major challenge that is the Rao Tula Ram Marg flyover.

Delhi’s unique challenges

One is the huge scale of the city itself. The task of managing all the resources necessary for smoothly running the entire city is overwhelming. To make things even more difficult, most of Delhi has grown organically over the years which makes managing utilities & infrastructure an arduous task. Add to this the irregularities commonly found in zonal and ward boundaries which are responsible for accountability of departments and you have a cocktail of a planner’s worst nightmare.

Secondly, there’s the departmental disconnect. In order to make the task of managing any city easier it is divided vertically into several departments.

In a utopian world, all these departments work together like the cogs in a Swiss watch. To compare Delhi’s departments to a cheap disposable watch would be unfair to the watch, as even they usually last for a year or two. This is the single biggest failing of the planning process in India, not just Delhi.

There is next to no communication between different departments and is a problem which every planner has to face over the course of their careers.

Political motivation is the third challenge. As long as there exists a democracy and vote banks, there will exist political motivation and pressures.

The sad part of these challenges is that they are seldom spoken of or taught in colleges to professionals.

The flyover mess

The problem with Delhi’s transportation is that it has unnecessarily long average trip lengths and trip durations. On average, a person spends close to 40 minutes to travel from their place of residence to their place of work, one way. The job of a transportation planner is to reduce these averages as much as possible. One important tool in their arsenal is the construction of flyovers.

What went wrong with the RTR project, from the beginning is the scale of the task. Since the location of the project was on an existing major route, it could not be shut down. This implies that heavy machinery can only be used for a few hours at night which also restricts the supply of materials to the site. This makes the task of construction more complex and most importantly, very slow.

Departmental Disconnect

A lot goes into constructing a flyover, clearances need to be procured from several departments (environmental, land acquisition, legal etc) and utilities have to be diverted so as not to hinder any existing mechanisms. Delay with any one of these departments is usually compounded as many clearances are interlinked.

The trickiest of these is land acquisition. Nobody wants their land to be acquired by the government and as a result the natural byproduct is resistance. Resistance from the poor and marginalised is no resistance at all (eg. Katputli colony — an entire village of artisans thrown out for a prime piece of land). Now consider the fact that this flyover runs next to a pretty posh locality where the rich and powerful reside, you get a different sort of resistance, resistance which makes a difference.

A proposal on paper faces no resistance except between the pen and the paper, its only once the proposal begins materialising that it faces systemic resistance from the structures which were meant to support it, and there is always a planner dancing between it all!