At the heart of Delhi’s food culture is the vast round universe of bread, which also kneads its diverse migrant population together. Most communities in Delhi consume bread as a staple food and making it often becomes a source of livelihood for migrants and immigrants.

Food is the closest link with home. When people migrate, they not only take their food habits with them but also their ideas of foods that are “good” to eat. The memories of food from home are dearest and the ideals of good food are reconstructed in an alien land that further shape a migrant population’s experiences.

The significance of food is more dramatic in the context of immigration, in conditions of vulnerability and marginalisation – as is the case of refugees and asylum seekers. To a lesser extent, this is true of inter-state migration in search of work or to escape from disputes back home.

Also read: Knocking on UNHCR’s doors proves futile for refugees

Food can take us to new places, encourage new encounters among people and allow us to observe societies from different perspectives. Rituals and cultural habits are ways to recreate the home and maintain the community feeling that they miss.

Taste of Afghanistan

The bustling alleys of Lajpat Nagar are witness to men in Pathani suits who have now integrated into Delhi’s social fabric, creating their own Afghanistan in a foreign land. Apart from succulent Chapli Kebabs and Qabuli Pulao, their thick, soft and chewy bread draw the most attention.

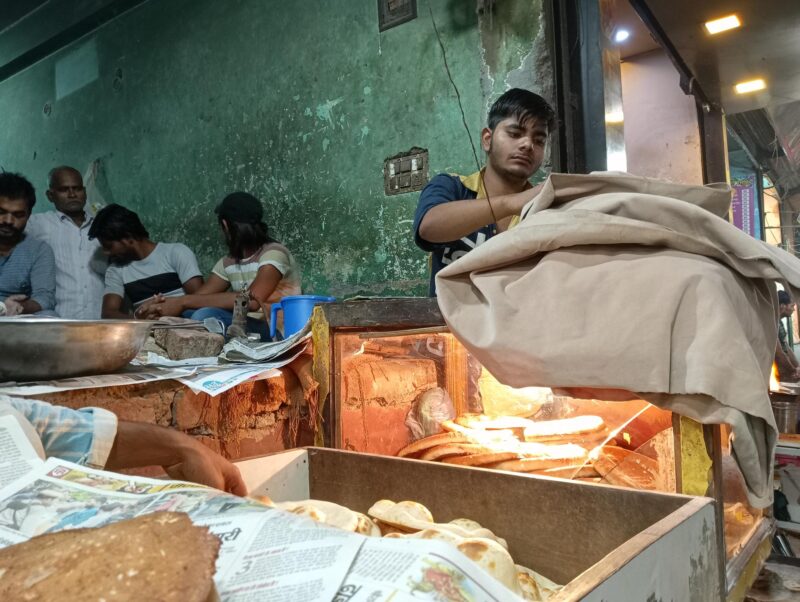

The sight of baked breads geometrically displayed in makeshift stalls is hard to miss. Every street in the colony has one local bakery. They are run by Afghan refugees who fled successive wars and lately the Taliban regime. They are primarily set up on a table by the side of the road.

Here passersby can choose from an assortment of breads and desserts: mounds of baklava, jowari, namki, tauti, shrinidor, cakes and doughnut-like sweets. They are made and sold by naanwais, mostly men, who roll out fresh rotis or naans throughout the day.

Afghan delights are not only popular among locals in the area that is inhabited by refugees from other countries such as Somalia, Iraq, Sudan, Lebanon sharing a similar Persian cuisine of bread, but also by other food aficionados.

Fresh favourites

“These are freshly baked every day for the simple reason that all our baked stuff, including the desserts are all sold out by night,” says Sulaiman, 43, one of the bakers at Kastur Bagh, a lane in Lajpat Nagar.

The Afghan bread shop has been running for the past four years outside Kastur Bagh, where many shops have signs in English and Dari (the official language used in Afghanistan). His is the only shop that has a giant machine, instead of a tandoor, to bake the bread.

The recipe is no secret: a mix of atta and maida, a pinch of salt. But don’t try this at home, as the machine is bought from Iran, and requires water to be sprayed on the bread from time to time.

Originally from Afghanistan’s Herat, Sulaiman lives with a family of four in Malviya Nagar, another enclave of Afghan refugees. “We sell around 700-1,000 pieces a day. Basically, it’s a supply system created for fellow refugees who have been living in Delhi for decades,” he adds.

While some shops are makeshift, some are part of bakeries, run out of homes where the popular Afghan rotis are also baked in bulk.

In fact, Kastur Bagh has a line of shops that sell a spread of breads and baked desserts. In one of these, 25-year-old Noori starts rolling out Afghan rotis from 7 am. He came from Mazar-i-Sharif in 2015 and has been living here since then. “Even Germans buy from us. Also Kashmiris! They love our breads and kebabs,” he says.

While Noori is busy lining rotis inside the tandoor, his friend Noorullah sits outside taking down orders from customers. “We left Afghanistan, but we brought our food here. One cannot be separated from one’s staple food for long. One way or the other, they will create it. We cannot do without our fat Afghan breads,” 22-year-old Noorullah says.

Close to 1,500 Afghan breads are sold by them every day and the final round of orders come even after 11 pm. “Not just Afghans, Indians who live around here love our food so sometimes we have to give in to their request even if it’s late. But we don’t complain because no one should be denied food,” he adds.

For preparation paraphernalia, the naanwais wake up at 5:30 am and begin work to serve the breads 7 am onwards.

Kashmiri kandur

Food consumption plays a central role in memory, comfort and adaptation to a new land and environment and even to social relations within and beyond the family.

The Kashmiri community loves rice, but have deep emotional attachment with their baker’s breads that are treated as individual meals, usually to be enjoyed alongside a piping hot cup of tea. Both the Hindu and Muslim communities in Kashmir relish a range of breads that are made in kandurs (local bakeries).

One such kandur is tucked inside Pamposh Enclave in the Greater Kailash area. Run by Kashmiri Pandits, this establishment beside Samavar restaurant holds onto the thriving legacy of Kashmiri breads.

“There are many types of traditional breads like taktach, Czot, katlam, kulcha, lavaas, roth and sheermal. These breads go well with salty pink tea called Nun chai (made with sodium bicarbonate). Only a few types of breads such as khameri and the regular naan are eaten with meat or veg gravies. Besides, bread is an integral part of social customs too – engagements, weddings, birth. So, apart from daily needs, we supply bread in bulk for such occasions,” says 29-year-old Chander from Kishtwar.

Chander starts working on all the ingredients from 4 am so that his customers can break their favourite bread. The bakery opens at 6 am and by 2 pm most of the first round of breads are sold out. “The first ones to sell are the white breads that are like khameri roti (it uses khameer or dry yeast). Bakerkhanis are made with maida and ghee, but the secret is in layering. We fold each layer with ghee. The kulchas are the last ones to be sold because it takes time to bake those. The traditions and recipes are handed down through generations,” he says.

Ambience matters

The breads are temptingly displayed on a shelf with a sliding glass for customers to get a better look at them before they place their order. “While regular water is used in making taktach, for sheermal we use moti elaichi, milk and more sugar. Katlam and bakerkhani are our special items here. It’s similar to a patty without a filling. Kulchas are like rusk biscuits, so they last the longest. People buy those in bulk, like 100 pieces at one go — we have to deliver 400 pieces tomorrow morning. you won’t get bakerkhani and katlam after 5 pm,” he explains.

“Many such Kashmiri bakeries are spread across Delhi-NCR. But in South Delhi, we have only this one, running for the past 15 years. Demand is high,” he says.

Enjoying a meal not only involves the process of eating but also the social setting and the social environment. That means the cooking of food and its consumption are rituals that are conducted on a daily basis.

During Patriot’s visit, at least 15-20 customers visited within 20 minutes. Some orders came on phone. “We sell almost 2000 breads every day. Sometimes more because of events where we have to deliver in bulk. In both Jammu and Kashmir, people drink 10 cups of chai – nun chai, kehwa, Lipton because of the biting cold and we need these breads for every cup of chai. Here, the consumption is still less.”

Chander’s family has bakeries back in Kishtwar as well. “I have been working here for 8-10 years as an employee, but we have such bakeries back home. In Delhi, my family lives in Rohini. I live here (at the back of the bakery) because it’s not possible to commute as well as run the business – we have to start our preparation at the break of dawn,” he says.

Malabar Parotta

Maintaining the cuisine and cultural food habits represents a strategy to recreate the “home” and the practical and metaphorical rituals for remembrance of the community feeling which migrants tend to miss. The same can be witnessed in Delhi’s Sarai Juliena.

This street near Delhi’s New Friends Colony is home to a large number of migrants from Kerala. Like other communities, they have brought their own bread – the Malabar parotta — to the national capital, which has now become a fan of its cuisine.

The roots of parotta are believed to be in the Tamil-populated Jaffna area of Sri Lanka, and the migrant labourers from there introduced it as Veechu parotta or Ceylon parotta while they were working in Toothukudi port in Tamil Nadu state.

Later, around the 1960s, this bread travelled to the Malabar coast and gained popularity in Kerala. By 1980, it became almost a staple dish throughout Kerala. “During the 1990s, street hawkers (thattukadas) of Kerala further strengthened its status as a local food, and it came to be known as Malabar parotta after the Malabar region of Kerala,” says Vinodh Sukumar (name changed), a cook at Hotel Malabar.

Known for its crisp, flaky taste with multiple folded and twisted layers, the bread is “generally served with a spicy coconut-based vegetable korma” but back home is relished with a meat dish.

“We are rice eaters but Malabar parotta is one of two breads popularly consumed in South India,” he says.

“Making of parotta involves a lot of oil. Even though the dough initially contains only a small amount of oil, during the process of making, oil is liberally incorporated. Egg adds softness to the recipe. It can be skipped, but street food vendors add eggs in their recipe. Next is milk. Milk adds richness to the parotta. You increase the amount if you want, but it’s a must,” he elaborates on the recipe.

The key challenge is to create the folds to make it flaky. “You need years of practice for that,” Vinodh chuckles.

In Juliena, migration of people from Kerala began three decades ago and today the street is swarming with everything that represents Kerala – Pazham pori, unniyappam, Pothu fry, appam, puttu, etc. along with aromatic spices.

Regular phulka

Three years ago, Mohammad Rizwan took the train from Bihar’s Purnia district to find work in Delhi. His best shot was to roll out fine thin phulkas because he had mastered the art back in his village for the past eight years.

“At home, I helped my mother because she had back pain issues so she couldn’t sit on the floor and roll out the balls. She kneaded the dough and I did the rest. My sister taught me to do that before she left the house after marriage. Slowly I got the hang of it and I started liking it, in fact. When I came to Delhi, I thought why not earn a living out of it! Thus, I landed up here and began doing what I do,” Rizwan says.

The 26-year-old “struggles to survive in Delhi because of expenses”, but rolling out perfectly round rotis “gives him immense joy”. “It’s such a costly place, but we have to survive, what else,” says Rizwan, who works as a roti maker in Zakir Nagar.

“It’s a kind of art. You know, at home we always saw our mothers, aunts and grandmothers do it. But only after you start doing these things yourself, you realise how extraordinary it is,” he says.

“We sell at least 1,500 to 1,700 phulkas every day. All of us together knead the dough and set up the fire, but only I roll out the rotis. We open the shop at 6 pm and work goes on till 12 am,” he says.

World of Chandni Chowk

Beside the iconic Karim’s is Rehmatullah Hotel that caters to poor and middle-class families with delicious Mughlai items since 1948. “My grandfather opened this hotel soon after Partition to feed those in Delhi who were marred by the aftermath of tragic Partition. At that time our shop was not even concrete. Then it later grew this big by God’s grace,” says Fazalur Rahman Qureshi, who is now the owner.

The 56-year-old supervises his staff from 3-6 pm as they serve the poor food for free. “The hotel bears my father’s name. My great-grandfather was from Agra, he migrated to Delhi decades ago. Today, we mainly serve food from Uttar Pradesh and Mughlai cuisine,” he says.

The hotel’s sheermal became so popular that they opened a separate stall only for such breads. “Our khameeri roti sells the most. But you can say that is because of the gravies it complements. However, sheermal is the most popular of all the breads. We can make it rich with dry fruits and lots of ghee,” he says, adding their services are open 24×7.

Meanwhile, a few lanes away, Meerut’s missi roti is selling fast. “The whole idea of food is to blend and unite people of different cultures. Our endeavour is the same. Even though we are from Delhi, we understand the need for these missi rotis during Navratri so we introduced this to our menu 50 years ago,” says Sudhanshu Gupta, the owner.

The stall named after Subhash Chand Gupta has been running for over 100 years — since 1921, to be precise. “People of UP should feel a taste of their home in Delhi, especially during festivals. So, missi roti is sold from Navratri to Diwali,” he adds.

Follow us on:

Instagram: instagram.com/thepatriot_in/

Twitter: twitter.com/Patriot_Delhi

Facebook: facebook.com/Thepatriotnewsindia