Having spent decades alone in confinement, Shankar, Delhi zoo’s lone African elephant awaits action for his rehabilitation, which might be his only chance at finding companionship

Shankar is the lone African elephant in the Delhi Zoo. A gift from the Zimbabwe government to former President Shankar Dayal Sharma, the elephant named after him, was brought to India in 1998 when he was just about two years old.

Zimbabwe, incidentally also happens to be one of the African countries which was down-listed in 1997 to Appendix II of CITES – a multilateral treaty to protect endangered plants and animals – which made it possible for its trade in live elephants, “to appropriate and acceptable destinations”. This could also very well mean that Shankar was captured from the wild and sent to India. We asked the Delhi Zoo director, Dr Sonali Ghosh, about the African elephant’s origins but were told that “the source of his acquisition was unknown”.

He had in fact been brought to India with a female elephant who was named “Bombai”, after the wife of Zimbabwe’s ambassador. She died just a few years later, as the annual inventory of the Central Zoo Authority from 2001-2002 accounts for, which also means Shankar has essentially been alone for almost 20 years.

His enclosure, no doubt, green and expansive, is nothing like the wilderness that an animal of his kind enjoys. When we reached, Shankar stood close to where people watched. Three boys catcalling the solemn elephant to their corner. The African elephant, with its massive ears setting it apart from its Asian cousin, stood stoic, then moved away slightly, to its left. Looking our way, swaying his head from side to side, he displayed signs of “stereotypic behaviour”, which are common psychological movements seen in stressed captive elephants, in repetitive movements like rocking, swaying, and head-bobbing.

It has been a long, lonely confinement for an animal which in the wild is known to have deep bonds with its kind. According to Elephants for Africa, young females will usually stay with the herd, whilst the males leave the herd during adolescence (between the ages of 10 and 19 years). Bull elephants are often seen with other male elephants to form small groups of their own, while much later in life lead more solitary lives.

Ghosh points to this very natural instinct shown in the wild, as to why Shankar’s current state of solo living wasn’t all that different. “Even wild African Male elephants in their natural habitat live singly and seldom come with herds except for breeding purposes.” She did tell us in written responses that they were looking for a mate, but it was impossible seeing as India has only one other African elephant in captivity, a male, named Rambo, in the Mysore Zoo.

Discussing the future plans for the elephant she said that keeping in mind “people’s sentiments and compassion for Shankar, Delhi Zoo is now embarking on a multi-pronged approach for providing a happy stress-free life to Shankar.” (sic). It includes: “Habitat enrichment and enclosure design augmentation; and writing to foreign zoos for finding a suitable mate and also for possible exchange.”

But an online petition recently started on change.org, which has till now received 14,494 signatures (at the time of filing) demands the release of Shankar. The petition by Youth for Animals started on October 2 calls for an end “from decades of solitary confinement in the Delhi Zoo” for Shankar. The petition says it wants him, “released to a wildlife refuge or sanctuary in Africa where there are ample African elephants. If that is not possible, he should be transferred to a sanctuary in India.” Nikita Dhawan, one of the petitioners said they would file a public interest litigation if the zoo authorities don’t take action.

They also seek the release of the only other African elephant in the Indian zoo of Mysore.

Before this petition was brought forward Ghosh spoke about Shankar’s rehabilitation, pointing to his home country being an inappropriate land to return to. “Shankar is a single animal, and it is true that there is no way we can find him a mate, at least in India Zoos. Can he be released back in the wild from where he came? In Zimbabwe? The developing African country is one of the few that trades in live specimens as per law, as it has a surplus population that needs active management. It may not take the animal back. Further it is also not clear from records whether Shankar was born in captivity or caught from the wild. Further, given stringent laws in India (that call for highest standards of wild animal welfare), animals can be exchanged only between zoos and most zoos have phased out (including in India) keeping elephants with them”.

There are however, many wildlife sanctuaries that may take Shankar, and even Rambo for that matter. In July this year, Howletts Wild Animal Park in Kent, UK, announced that 13 elephants would be flown more than 7,000 kilometres to Kenya, to be released in the wild.

Decades alone

While Shankar has been without a companion for most of his life, the Delhi Zoo houses two Asian elephants named Laxmi and Hira. They have each other for company, and their earlier signs of distress have reduced. This change came about with improvements made in their living conditions, according to the zoo’s annual report of 2020-2021. It states that the zoo made enrichment efforts, which included releasing both animals at the same time which brought about a positive change.“Both the Indian elephants were released at the same time in the enclosure and they were observed enjoying themselves and showed reduced stereotypic behaviour (swaying or bobbing their head)”.

So why can’t they be kept together? Trials to have the Asian and African elephant together, have not gone down that well. The zoo’s former Director, Ramesh Pandey had told us some months earlier that during morning walks, which the elephants are to be given for two hours daily, they tried to bring the three together but with Shankar “untrained (unlike the Asian elephants) and obstinate, it became difficult”.

Ghosh, the current director also points to the apparent training of the Asian elephants, saying “unlike the Asian elephant that can respond to commands and training (as was in vogue for captive elephants in forest plantations, for temples etc), the African species have never been tamed, nor is there evidence that they can respond to commands.”

Shankar, the annual report says, “is not well-trained elephant like other captive Asian elephants Rajlakshmi and Hiragaj. Managing him has always been a challenge. This year during “musth” he sustained severe chain burn injuries. However, with the help of well-trained mahouts we could well manage Shankar during the “musth” and were able to treat his chain burn injuries (sic)”.

Musth is a periodic condition in bull elephants characterized by highly aggressive behaviour and accompanied by a rise in reproductive hormones.

A decision was also made by the Central Zoo Authority (CZA) that the two species must be kept apart. We looked at the document on the first stakeholders meeting on upkeep of elephants in zoos in India, which took place in November of 2013. The then director Amitabh Agnihotri in his presentation said it was decided that the African and Indian elephants must be kept in separate enclosures.

And while the CZA ordered the two species be separated, it didn’t perhaps note how Shankar would be made to live the rest of his years alone. Interestingly, under its own recommended guidelines CZA says that elephants should not be housed alone, saying “It is recommended housing elephants in small groups and not as single animals”.

Then, KK Sarma, a Padma Shree awarded veterinarian wrote in the CZA’s quarterly magazine in 2020 that elephants should never be kept alone. “Elephants are intelligent, emotional, sensitive animals which form strong social bonds. They should never be kept alone; they must have company of their kind”.

Enquiry that led to Shankar

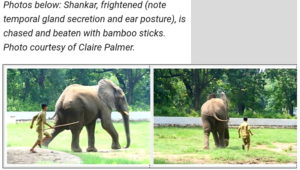

In a report from 2004, called the “Indian Zoo inquiry”, investigation by Shubhobroto Ghosh & Sanjib Sasmal found the plight of captive animals in India. In Delhi’s Zoo, it pointed to the plight of Shankar, who was said to be chained and abused.

The report also questioned the origin of the elephant; there are, it said, “major ethical questions surrounding the diplomacy issue which concern numerous live wild animals that are shunted from country to country”.

We spoke with Shobhobroto, who back in 2004, accused the management of the zoo for keeping Shankar in chains “majority of the day”, with being “seldom let out”. He had written that Shankar “is one of the most disturbed animals I have ever seen. He spends the vast majority of his day engaged in neurotic stereotypic behaviour, swaying in his chains under the shelter”. He also told us that Shankar would get whipped by his mahout.

Shubhobroto, however, believes that the African elephant’s circumstances have improved, with a much better enclosure and treatment, calling it drastically better than before, “but is it a bed of roses”, he asked rhetorically.

He had suggested after the inquiry that Shankar be sent to the Mysore Zoo “to live in the company of conspecifics”. He now says, his previous suggestion should still be considered by the zoo authorities which was, to give up Shankar to the Mysore Zoo to be with Rambo. “My principal suggestion was that the Mysore elephant and Shankar should have been integrated. Male elephants can live together if acclimatised, and given social space, so there’s no injury.”

And so, as suggestions are exchanged and even a petition for Shankar’s life in a sanctuary is dreamed of, he and others like him spend another day in the confines of a zoo.