This year, black artists made history with seven record wins at the Academy Awards. But is it enough?

“The word today is irony. The date, the 24th. The month, February, which also happens to be the shortest month of the year, which also happens to be the Black History month. The year, 2019. The year, 1619. History. Her story. 1619. 2019. 400 years…”

This is how filmmaker and actor Spike Lee started his acceptance speech, after winning his first Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay for his film BlacKkKlansman (sharing the award with Charlie Wachtel, David Rabinowitz and Kevin Willmott). Before starting the speech, he ordered the Oscars’ producers not to turn the clock on. Apparently, he said: “Do not turn that motherf**king clock on!” (and he was bleeped for it). But after three decades of being ‘snubbed’ by the Oscars, this was his moment to claim! And a proud moment for the Black artists all over indeed.

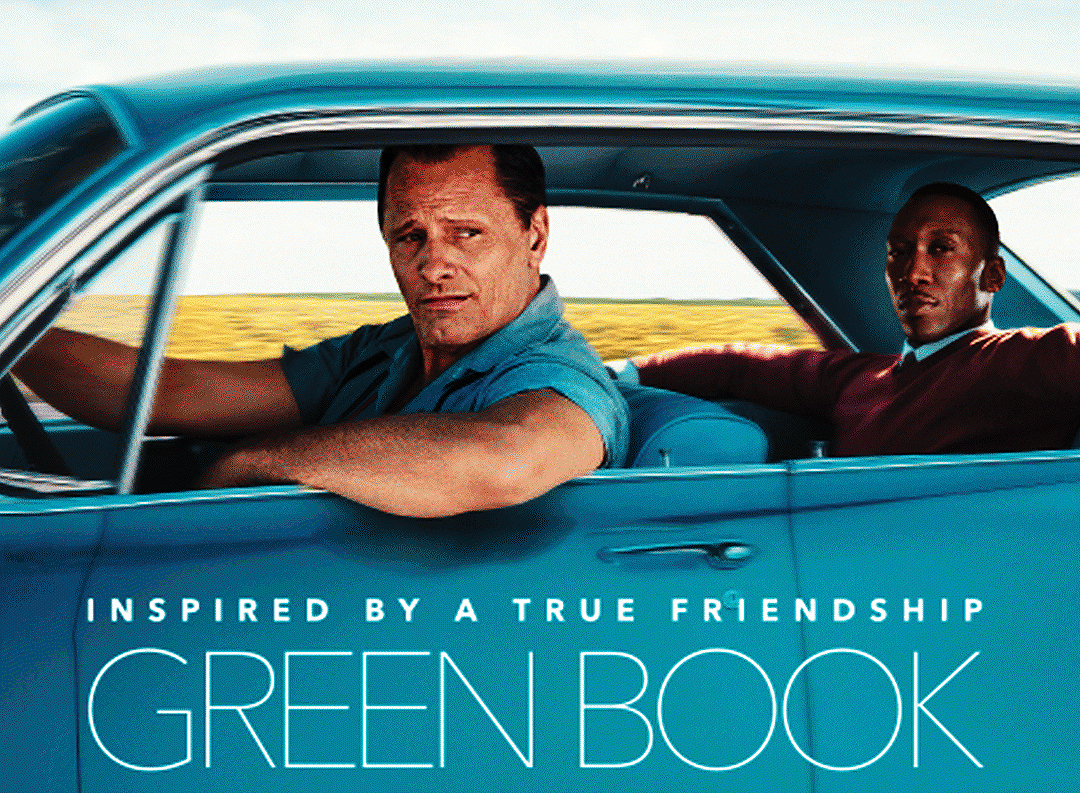

The 91st Academy Awards made history for recognising the achievement of black artists. This year, the Oscars saw as many as seven black winners – the maximum till date! Mahershala Ali, who won the Best Supporting Actor for Green Book, became the second black actor after Denzel Washington to be honoured with two Oscars.

“This was a long time coming,” says Ruth E Carter, who became the first black woman to win an Oscar for Best Costume Design for Black Panther, in her acceptance speech . Likewise, Hanna Beachler won the same for Production Design – a first as well! Then there was Regina King (Best Supporting Actress, If Beale Street Could Talk), Peter Ramsey (Best Animated Feature Film, Spider Man: Into the Spider Verse) and Kevin Willmott (Best Adapted Screenplay).

One can safely say that this marks the end of #OscarsSoWhite – the campaign which dominated 2015 and 2016. It was a protest by the black artists in Hollywood, who felt that they are not being represented by the Academy Awards fairly. In 2016, all the 20 nominations in the acting category went to white actors. This made actress Jada Pinkett Smith call for a boycott of the 2016 Oscars. It was the second year in a row when Black artists were snubbed by Oscars. With Moonlight winning the Best Film in 2017 Academy Awards, the change came along.

Even as black artists are getting their due, a big question has been raised by many, regarding how films portray the black struggle. This year’s Best Picture went to Peter Farelly‘s Green Book. The story revolves around the friendship of a black pianist and a white driver. They develop a bond, despite the racial differences – that too in an era of segregation.

But the film was criticised and ridiculed by many, including Spike Lee himself. He was visibly upset when the award was announced and almost left the Dolby theatres, but he was brought back. Later, explaining his reaction, he said: “the ref made a bad call.”

To put it in an understandable manner, one must take a look at an article on The Hollywood Reporter, which said: “Green Book is a Band-Aid film, covering up an open wound in need of stitches, while Lee’s BlacKkKlansman forces us to look closely at America’s racial wound and provides a means through which we can begin to heal it, though recognising there is no easy fix and the wound will still leave a scar on our country’s history. Green Book is a step back for the Academy Awards and a reminder that despite our ability to be honoured as winners, black stories still make us outsiders. Until the institutions in place are changed, metaphorically burned down with our righteous anger, we’ll remain so.”

In the last few years, such films have increasingly been recognised in the Oscars. In this context, films like The Help (2011), Django Unchained (2012), Selma (2014), Hidden Figures (2016), Fences (2017) and 12 Years a Slave (2013), should also be mentioned. One trait that is common in all the stories is that the time period is the pre-abolition time of slavery or the Civil Rights period.

According to many, only stories of black struggle and oppression are considered ‘Oscar-worthy.’ In an article, ‘Beyond Oppression and Struggle: Oscars films should celebrate Black excellence’, by The Cowl, it said: “Simply put, these films focus mainly on black struggle, without looking beyond themes of prejudice in order to pursue the more entertaining, hopeful stories afforded to white actors and filmmakers.”

The same thought resonated among many film critics, actors and viewers. In another article, ‘Black Films & the Oscars: Despair must not be the only route to prestige’, by indiewire.com, it opined: “The old industry joke is that black performers only receive Academy Award consideration if they portray stock characters such as a maid, buttlers, ‘magical negroes,’ slaves, mammies and other symbols of black pathology and misery. That still carry resonance today.”

In September 2018, Viola Davis revealed in an interview with The New York Times that she regrets playing the maid Aibileen Clark in The Help, for which she received an Oscar nod in Best Actress in the leading role category. In the interview, she said: “I just felt that at the end of the day it wasn’t the voices of the maids that were heard.” Though, the Oscars have done their bit – they have taken initiatives to bring diversity in all segments, but when it comes to the choice of films – are they still stuck in the same place? That is what many believe.

In his acceptance speech for Green Book, Farelly said: “The whole story is about loving each other despite our differences, and finding the truth out about who we are: We’re the same people.” Countering this, an article in Time.com said: “The contrast between these directors’ tones and viewpoints epitomizes a struggle over stories about race throughout Oscars history. To many, Green Book’s victory fits into a pattern of the Oscars rewarding safe, self-congratulatory and white-created films about race, in which a satisfying but ultimately false equality is achieved before the credits roll.”