Great works of literature have not done too well as movies whereas mediocre books do better. Film-makers must find a way adapt the missing word

More than a decade ago, in the afterglow of winning the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2001, VS Naipaul said that novels had outlived their utility and were likely to be replaced by cinema as a powerful form of storytelling.

With evidence from the intervening decade, it’s clear that Naipaul hurriedly erred in offering an obituary of the novel and overestimated the scope of cinema as a narrative device.

The spread and appeal of the cinematic language of stories hasn’t still posed an existential threat to the distinct ground of literary storytelling, particularly novels. That, however, leads to another set of questions: how have films fared in using literary narratives for telling onscreen stories? Limiting our gaze to Hindi films, how successfully, and seamlessly, have novels and plays lent themselves to cinematic adaptations?

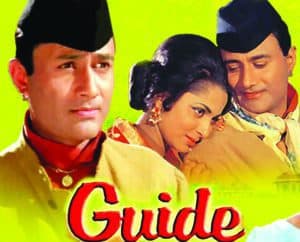

One can still be haunted by the disaster that RK Narayan’ novel The Guide became when it found an onscreen avatar in an eponymous film starring Dev Anand and Waheeda Rehman. Released under Navketan banner in 1965, the film’s Hindi version was directed by Vijay Anand while the English one by an American television director, Tad Danielewski.

In both versions, the film reduced the novel to a regular song-and-dance melodrama churned out by the commercial Hindi film industry. Far too many unimaginative detours from the novel, including the change of location essential to Narayan’s world, and the farce of it was hilariously lamented by Narayan himself in his essay Misguided Guide and also in his piece for Life magazine carried under the title How a Famous Novel Became an Infamous Film.

The following year, Hindi writer Phanishwar Nath Renu’s short story Mare Gaye Gulfam found a relatively better adaptation in Basu Bhattacharya’s Teesri Kasam (1966) starring Raj Kapoor and Waheeda Rehman. Perhaps Renu’s association with screenplay and dialogues of the film helped, though the language still lacked the authenticity of his narrative.

Earlier, Hindi cinema’s brush with mediocre novels with self-pitying and melancholic plots had already spawning box-office success. For instance, Bengali writer Sharat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s novel Devdas had already seen adaptions in Pramatesh Barua’s eponymous film in as early as1935, followed by Bimal Roy’s adaptation of the novel in 1955 and then Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s opulent version in 2002. If that weren’t enough, Anurag Kashyap offered a contemporary take on it in Dev D (2009).

On the contrary, and rather startlingly, mediocre works of fiction have lent themselves far easier to screen than great works of literature. Journalist Madhavankutty Pillai once attributed it to cinema’s inadequacy in portraying the thought process and complex ideas of characters on the screen.

“A novel’s quality often does not matter to its movie adaptation because cinema works at the surface level—there is no sophisticated way to depict thought as thought. You can have a voiceover in the background or enactment of emotion or, like the Bollywood shortcut of the 60s and 70s, a reflection in the mirror telling the character what he is thinking. There is always another agency needed to show thought. And absence of thought makes characters shallow,” writes Pillai.

He goes on to explain why even in the western chicklit-ish account of the US Civil War like Gone with the Wind, or more recently Slumdog Millionaire or Life of Pi, turned out to be appealing pieces of cinema made from ordinary and cliche-filled works of literary fiction. At the same time, repeated attempts to adapt more enduring and complex works of literature like Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment haven’t yielded convincing results.

To an extent, that also explains why 3 Idiots, a film inspired by Chetan Bhagat’s Five Point Someone, didn’t have too many literary expectations to meet and could spin the narrative with popular idioms from a plot that wasn’t demanding intricacies of thought, setting and language.

However, the parallel cinema movement in Hindi cinema witnessed some appealing cinematic translations of much acclaimed plays and novels. For instance,Vijay Tendulkar’s plays found their way to not only Marathi screen but also inspired art-house Hindi cinema in the eighties.

To his credit, Shyam Benegal has made two most engaging adaptations of literary fiction in his wide-ranging body of work. Ruskin Bond’s novel A Flight of Pigeons (1978) found an apt cinematic portrayal in Benegal’s Junoon the same year, and so did Hindi writer Dharamvir Bharti’s Suraj ka Saatvan Ghoda (1952) in Benegal’s eponymous film four decades later.

Journalist and novelist Manu Joseph, whose first novel Serious Men is being adapted for a film by Sudhir Mishra while the other two of his novels are also likely to be made into films soon, is of the view that filmmakers often get intimidated by the intellectual value of literature. That perhaps causes lot of confusion and work which belongs neither to literature nor to cinema. He feels that complex thought or reflections of characters can be left out if filmmakers find it unfit for cinematic tales and they need to develop their own way to deliver the core of literary narrative.

In times when storytelling is witnessing an explosion of possibilities with multiple avenues offered by technology, the craft and ambition of literary storytelling on the Hindi screen is still to come of age. That should challenge a generation of Hindi filmmakers to break new ground in blending the visual universality of cinematic language with thoughtful and culturally evocative voices spread across pages of literature.