As football continues to be played in front of empty stands in the stadium, broadcasters are using virtual fan chants to make the action look more real

When Manchester City’s Raheem Sterling scored the first goal of the restarted Premier League season on Wednesday night, the cheer heard by viewers watching on TV came from a match played in the past.

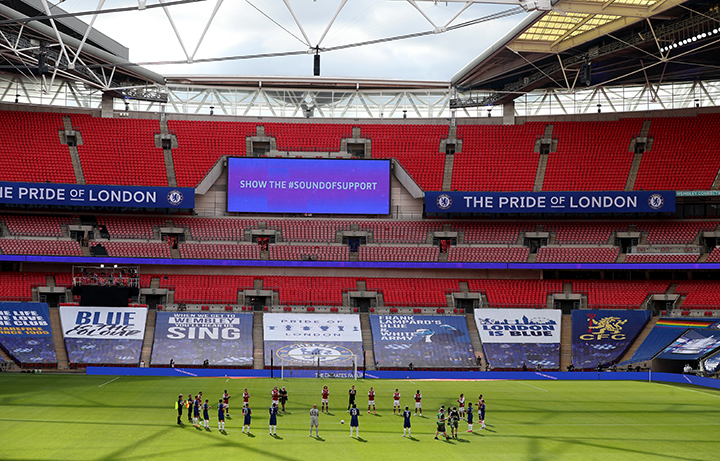

With restrictions due to the pandemic, fans aren’t allowed on the grounds. All fixtures for the foreseeable future will be played behind closed doors. Instead, TV companies are turning to technology to provide a virtual atmosphere.

Anyone who’s watched a game without fans in attendance will know what a sterile experience it is. The lonely shouts that echo around the empty stadium are quite the opposite of what fans expect when they watch a game of football. The noise, the chants, the songs, all add a magical flavour to the match.

So, when the football schedule post restart was broadcast, the answer came from EA Sports and FIFA 20 – a series that has been doing its very best to recreate the slickness and sheen of televised football since it started using audio recorded at actual matches in 2014.

After every Premier League ground was added to FIFA15 a year later, each one now has its own in-game soundtrack, created using audio recorded by Sky during its live broadcasts, which ebbs and flows in response to what’s happening on the pitch.

It’s this library of football foley sounds (the reproduction of everyday sound effects that are added to media in post-production) that is being used to construct an atmosphere at each of the remaining games when they’re shown on TV.

That’s why when Raheem Sterling put Manchester City ahead just before halftime, the cheers were actually from an old game at Etihad that had already been broadcasted.

So how does it work during a live game? EA Sports provided Sky, the official broadcasters with around 13 hours of audio, including team-specific chants, ‘oohs’ for near misses, and howls of derision for when decisions don’t go the way of the home team.

Rather than just forming a bland sonic wallpaper that doesn’t reflect the flow of the game, a sound engineer combines these on-the-fly with the live audio to create something akin to a match being played in front of 50,000-odd fans.

Obviously this introduces situations where the engineer must decide how they think a real crowd would react, which could lead more partisan fans to accuse the broadcaster of their favourite thing: bias against their club.

According to a statement by Dave Gibbs, Content and Product Director at Sky Sports, the official broadcasters of the Premier League there are no official guidelines for the sound engineers to follow. “You’re relying on the skill of the engineer to mix it in real time,” he goes on to say. “Ours really understand the flow of the game and how that audio experience works.”

Fans can still influence what’s heard, albeit in a slightly gimmicky way. Those watching through Sky’s app or via the website can use a new Fanzone feature to vote on which chants they want to hear from a carefully chosen selection of TV-friendly options.

As with pretty much everything in football, the virtual crowds have divided opinion, but when former footballing legend Gary Lineker polled 180,000 of his Twitter followers on the issue, 75% said they preferred it.

“A football match in an empty stadium is just not good enough”, says engineer Abhik Sarkar, who is a devout football fan. “I remember watching the Manchester United vs LASK Europa League game and it seemed so odd without crowds. At least the sounds have made a big difference”, he adds.

Many welcomed the dose of familiarity the added audio provides in an otherwise unprecedented situation, while some have bemoaned the fact that it doesn’t match the action on the pitch closely enough.

While it’s perhaps unfair to judge the tech on just two games, with production teams still coming to grips with an entirely new process as they go, it’s easy to see where both sides are coming from.

When Sheffield United’s Enda Stevens fired a shot into the side-netting against Aston Villa in the opening game a cheer erupted, as it often does when fans mistakenly think their team has scored, but it faded away just a little bit too quickly.

Perhaps the biggest giveaway that it wasn’t real, though, was the fact that it wasn’t met by jeers from the opposing fans. Similarly, when Raheem Sterling tripped over his own feet towards the end of Manchester City’s win over Arsenal, there was no mocking from the virtual away end.

On the whole, while the general sonic backdrop is pretty effective, the reactions have felt just a little too delayed. It was telling that the most convincing noise on opening night came after Manchester City’s Kevin De Bruyne scored his 51st-minute penalty, when the audio engineer in charge of the cheers would’ve had more time to prepare the response.

La Liga has also chosen to superimpose a texture onto each stadium’s lower tier in an attempt to make it look like the seats are filled with fans – a rudimentary alternate reality (AR) effect. If you focus on it, it inevitably looks a bit odd, but when your eyes are on the game, its presence in your peripheral vision seems to play some sort of trick on your brain.

The crowd sounds also seem to be better integrated into the audio mix and genuinely sound like they’re coming from within the stadium.

“I don’t think it’s quite ready yet. There are a lot of technical challenges there,” says Gibbs, suggesting the ball could get lost easily among the overlay.

The flags and banners covering the empty seats at Villa Park and the Etihad Stadium, however, seemed to have the opposite effect, merely serving as a stark reminder of what was missing.

With real crowds at stadiums expected to be one of the last things to return to normal as Covid-19 is brought under control, it’s a choice that fans at home will have to make for some time to come.

(Cover: The FA Cup final being played in an empty Wembley Stadium // Photo: Getty)