Despite a decade-old legal ban, Delhi’s manual scavengers continue to work at society’s margins, haunted by the daily threat of death in toxic sewers. On September 16, a 40-year-old labourer died in Ashok Vihar Phase-II, northwest Delhi, after being sent into a manhole without protective gear. Two of his colleagues remain in critical condition — one collapsed after inhaling fumes, while another who tried to rescue him also lost his life. Police have registered a case against the contracting company.

The incident is the latest in a series of deaths that expose the persistence of manual scavenging in the capital, despite repeated assurances by civic bodies and strict orders from the Supreme Court to eradicate the practice.

Delhi fares worst among states

The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and Their Rehabilitation Act came into force in 2013. In 2023, the Supreme Court again directed states to eliminate the practice. Yet across Delhi, workers can still be seen climbing into noxious manholes and drains.

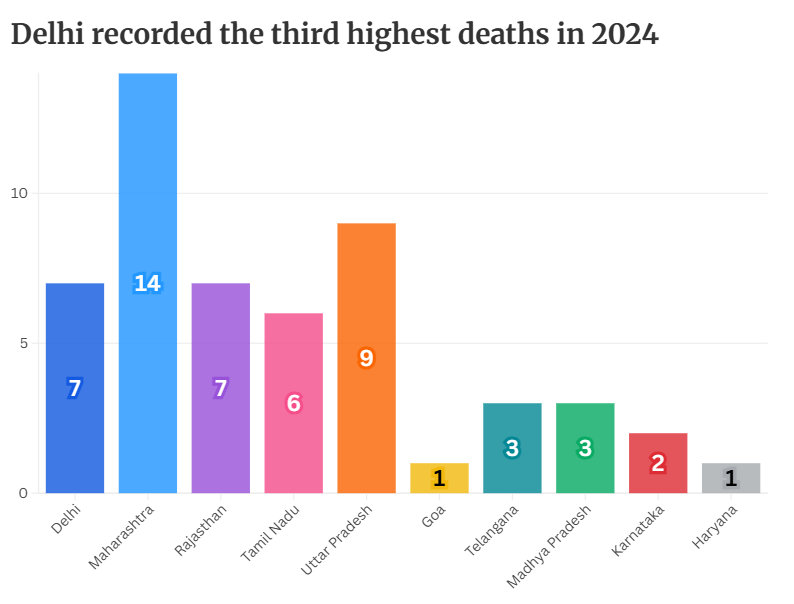

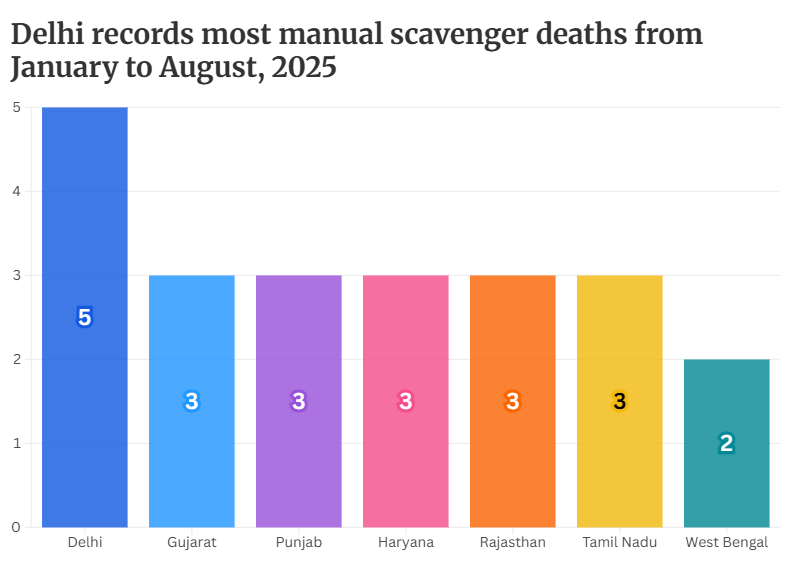

According to the National Commission for Safai Karamcharis (NCSK), five sewer-related deaths occurred in Delhi between January 1 and August 31. With the September 16 death, the toll rose to six. In all of 2024, seven such deaths were reported. Delhi now ranks the worst in the country for manual scavenger deaths this year, and none of the victims’ families have received compensation.

Gujarat, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Haryana, and Punjab follow closely, each recording three incidents during the same period.

The Paschim Vihar tragedy

On July 8, two workers, Brijesh, 26, and Vikram, 30, died while cleaning a sewage treatment plant at Sri Balaji Action Medical Institute in Paschim Vihar, west Delhi. They had been deployed to clean the carbon filter and were reportedly not provided with protective equipment.

Both men, originally from Hardoi in Uttar Pradesh, were the sole breadwinners for their families. Vikram is survived by his wife and four children, while Brijesh leaves behind his wife.

Although the exact cause of death is under investigation, family members gathered outside the hospital demanding justice. “Initial investigation revealed that the two deceased fell unconscious whilst maintaining a carbon filter, a task being carried out by a contractor at the hospital,” said Sachin Sharma, DCP (Outer).

A hospital worker alleged that Brijesh had been forced to re-enter the septic tank despite earlier complaints. “Earlier in the day, he came out complaining of a severe headache, but his plea was ignored. That evening, at around 6:30 PM, Brijesh and Vikram were told to re-enter the tank. Brijesh refused but was forced inside, and eventually, he died. Sadly, this time, neither of them came back,” the worker told national media.

In a statement, the hospital said: “An unfortunate accident took place at Sri Balaji Action Medical Institute, Paschim Vihar, New Delhi. Workers of Friend Environment Enviro Engineers, responsible for the operation and maintenance of the sewage treatment plant, were undertaking servicing of activated carbon filters. Brijesh and Vikram met with an accident during this task. The hospital staff rescued them promptly, and they received the best possible treatment. Regrettably, despite our best efforts, they could not be saved. The hospital is fully cooperating with local police authorities in their proceedings.”

Fatal work in New Friends Colony and Narela

On March 18, three workers — Panth Lal Chandra, 43, Ramkishan Chandra, 35, and Shiv Das, 25 — entered a sewer manhole at Friends Club in New Friends Colony, southeast Delhi. They lost consciousness, likely due to toxic fumes or lack of oxygen. Panth was declared dead, Ramkishan remained in critical condition, and Das stabilised.

The Delhi Jal Board (DJB), responsible for the sewer, denied employing the workers, claiming it was an unauthorised entry. A senior police officer contested this, saying the men would not have entered without DJB approval and criticising the absence of safety gear. Police registered a case under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) for culpable homicide as well as provisions of the 2013 Act.

On February 21, at least two sanitation workers were killed and another injured in Narela, outer Delhi, after descending into a sewer near Manisha Devi Apartments. Police said they had been hired by a private contractor.

A life on the edge

For Baldev Rajsahi, a resident of Ghazipur and often called to clear local drains with his friend Rakesh, safety gear has always been absent.

While he usually works as a plumber, sanitation jobs with the Public Works Department (PWD), the Municipal Corporation of Delhi (MCD), and the DJB help him survive. “It’s illegal, but I cannot help but work,” he says. “It’s my compulsion. Safety and precaution—these are afterthoughts. I have raised concerns, but there has to be someone willing to listen.”

Across Delhi and India, manual scavengers — typically from marginalised castes — face death by asphyxiation from gases such as methane and hydrogen sulphide. Despite the 2013 Act, the capital’s sewers remain deadly workplaces.

The law and its loopholes

The Act defines a manual scavenger as anyone “engaged or employed… for manually cleaning, carrying, disposing of, or otherwise handling… human excreta” in insanitary latrines, open drains, pits, or other spaces before decomposition. Its mandate is clear: abolish this practice and rehabilitate workers. Yet the Delhi government insists manual scavenging no longer exists — a claim contradicted by the mounting toll.

Civic bodies such as the MCD and DJB outsource sewer cleaning to private contractors, with tenders awarded to the lowest bidders. “They haven’t hired permanent sanitation workers in over two decades. Everything goes through these private agencies,” says Azad Mehra, DJB field assistant and Centre of Trade Unions (CITU) member.

In March, the DJB listed 99 open tenders for sewer management and repair across the city. Even with mechanised solutions, reliance on human labour continues. In August 2023, the DJB admitted that 189 contractors supplying sewer-cleaning machines were in “critical condition” due to unpaid invoices, hampering mechanisation. When machines fail, untrained and unprotected workers are sent down instead.

Also Read: Over 23% unidentified bodies found in north Delhi in a month

A senior DJB official rejected allegations of employing manual scavengers, citing the Supreme Court’s order and the 2013 Act: “We do not employ manual scavengers or companies supplying them. We only float tenders for the deployment and utilisation of pumps and machinery for sewer cleaning.”

On January 30 this year, the Supreme Court ordered a complete ban on manual sewer cleaning across six metros — Delhi, Mumbai, Chennai, Kolkata, Bengaluru, and Hyderabad — directing civic chiefs to submit affidavits by February 13. No such development has followed.

A cycle of exploitation

The hiring process remains informal and exploitative. “There are no forms. Somebody comes to the jhuggi, asks if we want work, tells us what to do, and we show up at the site,” says Rahmat Ali, a Ghazipur resident. “Sometimes there’s no work for days, even months. We scrounge for anything—cleaning drains or dry waste at least gives me steady employment.”

Jony, another worker, describes the risks: “Each time, it feels like I’m risking my life. Sometimes an agency gives me a helmet, boots, and gloves, but never a harness. Often, there’s nothing.”

Mehra adds: “These workers aren’t trained. Agencies treat them as expendable. To earn a wage, they stop caring about the risks and go in unprotected.”

The Social Justice and Empowerment Ministry reported 58,098 manual scavengers in 2021, but the NGO Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA) estimates more than 7,70,000, underlining the true scale of the crisis.

Deadly pits of disadvantage

Mehra summarises the situation starkly: “Workers, mostly from disadvantaged castes, go down into these pits. They become their graves, and no one raises a finger. Unreported cases are written off as accidents.”

Socioeconomic desperation forces workers into this trade, leaving them with a choice between starvation and suffocation.

A systemic failure

The persistence of manual scavenging in Delhi reflects systemic failure — a combination of bureaucratic denial, economic exploitation, and societal indifference. The 2013 Act promised rehabilitation, but enforcement remains weak. Mechanisation falters, and the poorest continue to suffer.

On September 18, the Supreme Court fined the PWD Rs 5 lakh after labourers were found manually cleaning sewers outside the court complex. The workers had no protective gear, and a minor had been employed.

A Bench of Justices Aravind Kumar and NV Anjaria warned that repeat violations would lead to criminal cases against officials. The penalty is to be deposited with the National Safai Karamchari Commission within four weeks.

The issue surfaced after senior advocate K Parameshwara submitted a video showing workers manually cleaning outside Gate F of the Supreme Court, with photographs confirming the absence of safety equipment.