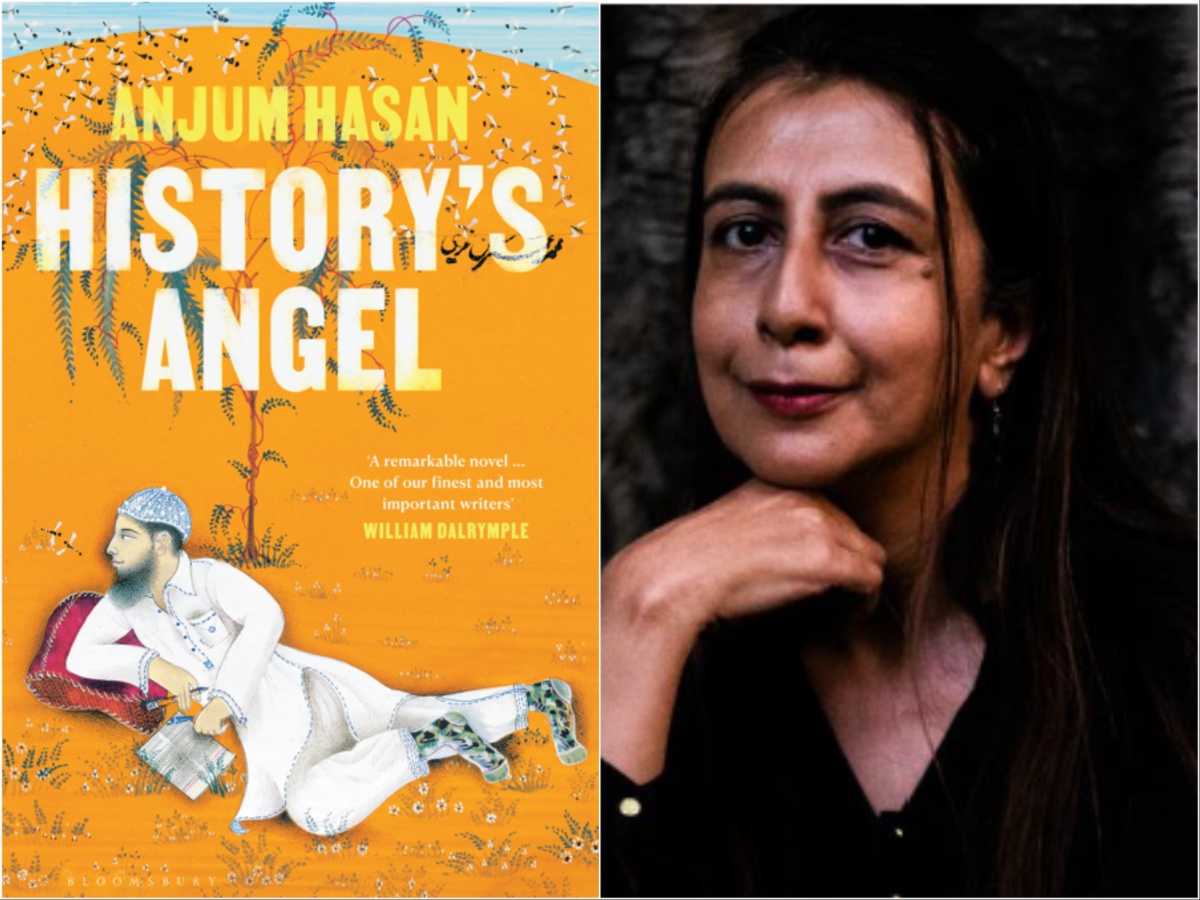

Anjum Hasan’s latest novel, History’s Angel, is a story set in present-day Delhi with Alif, a history teacher, its chief protagonist.

Being set in the heart of the capital, the story resonates with anyone who has lived in or knows Delhi well. Several scenes are set in well-known neighbourhoods of the city. Hasan describes, for instance, the hustle and bustle of Delhi, “a city made so intensely, so noisily of now” – Delhi metro; Oberoi Hotel; National Gallery of Modern Art; Lalit Kala Akademy; the roundabouts of Lutyens’s Delhi; glittering malls in Greater Kailash, Saket and Vasant Kunj; and Malkaganj Road’s noisy streets, teeming with numerous shopkeepers.

Through Alif’s character, the author also provides insights on Delhi’s rich historical past, including the medieval Delhi sultanate and the Delhi renaissance. She also devotes a lot of the text elaborating on the beauty and timelessness of the city’s exquisite ancient monuments and hotspots such as Qutab Minar, Purana Qila, Red Fort, Jama Masjid, Delhi Gate, India Gate and Shahjahanabad.

Also read: This Master’s Voice

The prose is also peppered with many references to popular landmarks in the city, such as the University’s north campus, Chandni Chowk, Nehru Place, Mehrauli, Sarojini Nagar, Jamia Nagar, Karol Bagh, Daryaganj, Pitampura, Sadar Bazar, Rajendra Nagar and Mathura Road.

Here is an example of a powerful description of old Delhi’s Urdu Bazaar:

“A hundred different enactments of daily commerce – sellers of fly-speckled dates heaped in all shades of brown; squawking cages with scrawny chickens and fluff balls of yellow chicks; biryani rice boiling in a huge cauldron of cloudy water and a man testing one grain between two fingertips; another man outside on his haunches contemplatively smoking his hookah; a hopeful woman with nothing but a tiny heap of garlic cloves for sale; men in spotless white presiding over festering goat trotters; a bookshop with signs for sale that all say the same in different calligraphed Urdu words, Khushahmdeed, Istiqbaal, Tashrif Layeye – that is, Welcome and Welcome and Welcome; heaped on the pavement an incredibly emaciated beggar with a bald head the size of an infant’s, and even more emaciated child asleep on her lap.”

Along the way, Hasan also elucidates on the not-so-great aspects of “the often smoggy, often small-hearted” city, such as its horrific pollution levels and “the many circles of hell that are Delhi’s roads”, even though she proclaims later that “anything is possible in Delhi.”

Among other things, the novel also ponders, time and again, on the burning question of what it means to be a Muslim in contemporary India. When Alif and wife Tahira, who is preparing for her MBA, go to see a house in Noida, the property owners poke questions at them, pointedly jabbing at their Muslim identity. The author also mentions the contentious National Register of Citizens, which taken together with the Citizenship Amendment Act, is part of the government’s plan to marginalise Musims in the country, critics say.

Tahira also feels stereotyped for being a good cook simply because she is a Muslim woman. She wonders if that’s all people assume them to be.

“Bawarchis? Poetry-spouting fools with minced mutton coming out of our ears, thinking only of Allah and pining only for behesht between mouthfuls of zafrani pulao?” she thinks aloud.

The author also highlights repeated debates in television news – “the same thing all over again: Muslims should, Muslims can, Muslims need to, Muslims are…” The novel also probes into Partition and the idea behind it, explaining how the Hindu-Muslim divide only began after this mammoth, catastrophic event.

Overall, an engrossing read, encompassing India’s past, present and future.