VP Singh believed that historically, any real change comes through an element of ruthlessness or not at all. Whether it was his firm stand on corruption, Raid Raj or the implementation of the Mandal Commission report, he wanted to be a disruptor rather than gain power for power’s sake

Thirteen years after his death on 27 November 2008, retired journalist Debashish Mukerji has come out with a definitive biography on India’s eighth prime minister VP Singh. His tenure may have been short (1989-90) but his impact on politics at the national level was phenomenal, especially as finance minister. He challenged Rajiv Gandhi at the height of his power on a matter of principle – corruption in defence deals – and for this alone deserves much more accolades than he has got so far.

With Uttar Pradesh scheduled to get a new Legislative Assembly in February, it’s definitely instructive to see what VP Singh achieved as UP chief minister. For that, you have to read the book, in which the flowing narrative is backed by impressive research. To give a glimpse, here is an interesting episode. When Lal Bahadur Shastri visited his constituency Allahabad in 1965 soon after becoming PM, Singh pricked his own thumb with a blade and used the blood to mark a tilak on Shastri’s forehead.

Two years later, when his elder brother Sant Bux Singh contested the Lok Sabha seat from Fatehpur, the four brothers would impersonate the candidate during their campaign in remote villages with no electricity. ‘We would request villagers not to raise their lanterns high enough to clearly see the candidate’s face, claiming that Raja Sahib could not take the smoke’! And that is how Sant Bux won by 25,000 votes. Unfortunately, their relationship soured when Indira Gandhi chose Singh to join the Union cabinet when he was just a first-time MP. His loyalty to Indira Gandhi did not waver during her lifetime, even during Emergency, when he stood by her.

On 7 June 1980, the PM summoned Singh and told him not to refuse if he was made UP CM. The author does not draw a parallel, but it sounds just like what happened in 2017 to Yogi Adityanath, then a fourth-time MP, when the Modi-Shah dispensation decided to make him CM. Singh too was not an MLA at the time he was sent to lead UP, a job he could hold only for two years. Then, as now, the Congress MLAs were not given a chance to elect their CM. They did, however, hold a meeting and pass a unanimous resolution that Sanjay Gandhi should take up the job! It boded well for UP that the son of the PM was not the least interested in becoming a regional satrap, though today his son Varun might be.

VP Singh always stood on principle to the extent of seeming eccentric. ‘In his political career, VP Singh had always worked hard, but the load on a chief minister staggered him initially,’ writes Mukerji. Which led to piquant situations. As he found time to tackle his files only in the wee hours, his wife Sita Kumari had to remove her reading glasses while handling files so that secrecy was not breached. Again, when a villager challenged him, asking their CM what he had done for them, he replied, ‘I’ve done nothing but I’ve been a symbol of honesty.’ It was his failure to wipe out all dacoit gangs in a month’s time, as he himself promised, that led to his resignation as CM. No wonder, his next assignment, as Union commerce minister, was comparatively less tumultuous.

Five years before PV Narasimha Rao liberalized the economy, VP Singh as finance minister started the process of unshackling private industry. About his 1985 budget, a leading newspaper wrote a front-page editorial that it would ‘break many of the decades-old shackles on the initiative and enterprise of the Indian people.’ To mollify critics from the Left, he said it was not a departure from the path of socialism. In the next budget, he introduced Modvat, precursor to GST. Unfortunately for the country and for Rajiv Gandhi, he was shifted to defence, where the West German submarine company HDW refused to agree to a reduced deal, saying it had already paid 7 per cent commission to an Indian agent. He resigned on the issue, and five days later the Bofors scandal broke. History would have been different if he had accepted Zail Singh’s offer to dismiss Gandhi and make him PM. But his conscience did not allow it and he became a rallying point for Opposition forces.

In the current scenario, it is interesting to see how the National Front cobbled together in the years that followed could not provide a stable government for India. With the collapse of the Congress, we are unable to get a two-party system going in India, which has an alphabet soup of regional parties whose leaders think they can overthrow the BJP if only they can stitch together an alliance: TMC, TDP, AAP, NC, NCP, TRS, LDF. His Jan Morcha had to contend with the overweening ambitions of the likes of Devi Lal, Ajit Singh, NT Rama Rao, Chandra Shekhar, etc. Though he was sworn in as PM in December 1989, ten weeks later there was ‘mayhem in Meham’, as the media gleefully called it, and his government began falling apart.

VP Singh’s failing health, like Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s, was most unfortunate as it prevented him from staying centrestage in India’s politics. His kidneys started failing after his impetuous fast to stop communal violence after the demolition of the Babri Masjid, as he failed to drink enough water. For eleven years, from March 1997 until his death in 2008, he was on dialysis, an astonishingly long treatment that could obviously not go on forever. Then he contracted cancer of the bone marrow and started chemotherapy in 2004, and lived for another four years.

Seven days mourning was officially observed upon VP Singh’s death but his name does not crop up much when milestones in India’s development are discussed. This is probably because he was firmly against the perpetuation of his dynasty, yet another proof that the man lived by his principles and did not indulge in double-speak like most politicians. No wonder an earlier biography by Seema Mustafa was titled ‘The Lonely Prophet’.

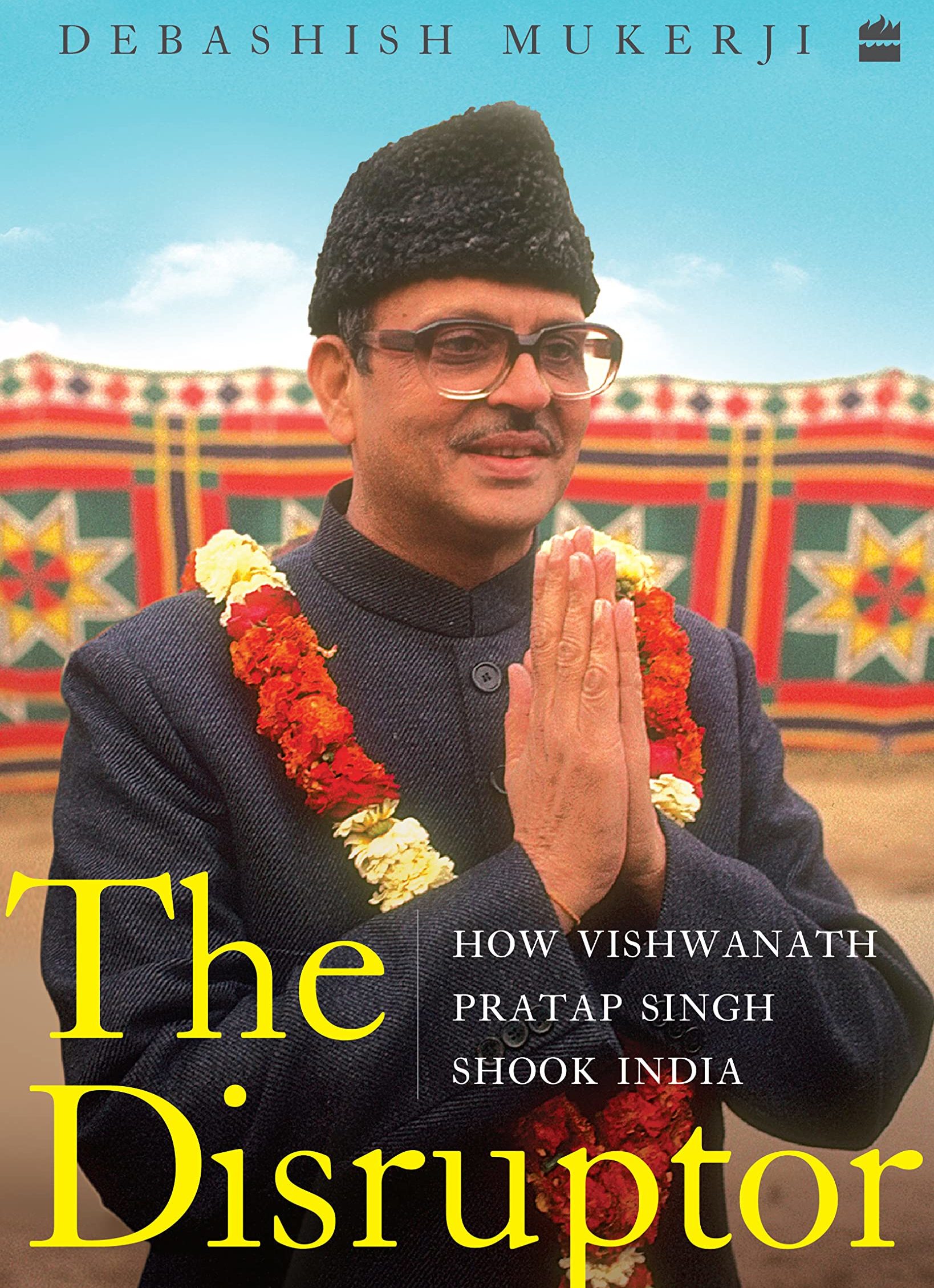

The Disruptor: How Vishwanath Pratap Singh Shook India by Debashish Mukerji, HarperCollins India, 542 pages, Rs 699/-

(Cover: Amazon.in)