Patriot scrutinises the censor records for the period 1920-50, recently declassified, which give an amusing glimpse of the scenes which were scissored in those days

Filmmaker Steven Spielberg once said, “There’s a fine line between censorship and good taste and moral responsibility.” And India’s Censor Board or to be precise, the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) has often blurred the line.

Last year, 2018, India’s censorship completed 100 years. The relationship between cinema and censorship has been more like a love-hate one. Controversies have seldom left its side.

Be it 1996’s Fire – the film which dared to show on-screen lesbian romance. Or be it 2016’s Lipstick under my Burkha – which explored women’s sexual desires. The CBFC has been a barrier to both these films – the same old ‘patriarchal’ and ‘orthodox’ reasons being cited.

Let’s rewind

But how about the initial years? The 1920s or 1940s. Ever wondered how censorship or certification used to function back then? Thanks to the National Film Archives of India (NFAI) – which recently released the Censor records (from 1920s to 1950s). Thereby giving a glimpse of what worked and what did not work back then.

Going through the records, one can definitely see a pattern – a big NO to drinking scenes, intimacy between the actors, nudity and a lot more they deem ‘vulgar’ or ‘obscene’ or ‘objectionable’. Let’s take a look at some of them!

No stripping!

– The Virtuous Model (1920): The whole scene showing the heroine undressing before she comes out in her wrap

– Lal Dupatta (1948): Cut out the close-ups of busts and showing of hip movements of Sukhia in song No 2 when she steps out after taking a bath

– Balma (1948): The bathroom scene should be considerably reduced and all close-ups of Balma’s bust, while she is shown sitting in the bathtub should be deleted. Cut out all direct and indirect references to nudity (like ‘main coat kaise utaru’)

– Girls’ School (1949): Cut out the scene showing Papita lying on the bed reading a book with her chest exposed till she covers it up with her hands

– Dil ki duniya (1949): Cut out the showing of Lalna’s legs before going for a bath

– Aparadhi (1949): Cut out the whole scene where Madhu’s wife is shown without covering garment (odhani)

– Tarzan & his mate (1934): In the scene where a nude man is showing getting into a bath tub. Omit the scenes showing a silhouette of a nude girl dressing. In the scene where Tarzan and his mate are shown swimming under water, curtail drastically part of the scene showing the close ups of the girl with exposed breasts

Touch me not

– Dil ki Awaz (1948): Omit the two scenes – one showing Dilip holding Angi tight with his arms round her waist and the other where Dilip is sitting close to Angi and caressing her

– Jadui Shehnai (1948): Scene where Chandrabala is shown lying with her head resting on the lap of Veer Singh and both sitting on a hammock

– Dukhiyari (1948): Cut out the sequence where Miss Kanwal (a dance girl) is shown lying on the lap of Seth Kantilal and where she is again shown resting her head in his chest, together with the close ups

– Nanand Bhojai (1948): Cut out the love scene between Manohar and Usha in the gharee

– Chunaria (1948): Cut out all embraces of Chandani with Mohan and Kumar except one with Mohan. Cut out the scene showing Chandani lying on the lap of Kumar after the dance

– Ram Ban (1948): Cut out the embrace of Rama and Seeta under the shower

– Ma Bap ki Laj (1948): The scene in which Vimla falls in the lap of her lover, who is seated on the sofa, also cut out her sitting in the lap and their attempt at kissing

– Sanwari (1948): Cut out the scene in which Kitty is lying on bed and is putting Laloo’s hand on her breasts

Language, please!

– Dil ki Awaz (1948): Omit the words Chamar or Bhangi

– Heer Ranjha (1949): Cut the dialogue “Dekhati hu ladka kaisa nahi hota”

– Taqdirwale (1948): Delete the sentence “Mujhe toh roj naya bulbul chahiye” (Every day I need a new girl)

Homophobia much?

– Apna Desh (1949): Delete the shot showing the younger brother of the hero using lipstick

– Neki aur badi (1949): Nandan in woman’s clothes may be shown only once on the steps. His visit to the restro (sic) and the whole of the restro scene should be cut out

Funny, not funny

– Varasdar (1948): Cut out the scene showing Vinaya smelling the lady’s sandal, lifting the lady customer’s saree and consequently being beaten by her

– Chanda ki Chandani (1948): Cut out the hip and waist movements especially the shot of the side to side movements in the dance called the gypsy dance before the lake

– Deep Waters (1948): Cut out the close-up of Hod and Ann rubbing their cheeks against each other while dancing

– Actress (1948): Cut out the mouth to mouth kiss of the two sisters Kamin and Ragini

– Andaz (1949): Delete the scene showing Neena falling on her father when she goes to wake him up

– Jai Sindoor (1949): Delete the reference to Jai Shakti and Jadui Danda. Delete the two semi-close-ups of the dancer shaking her busts vigorously. Cut of all the shots showing hip to hip and back to back movements of the dancers close to each other

– Sunehre Din (1949): Cut out all shots in song No. 1 showing Renu’s exaggerated hip movements near the camera

– Thes (1949): Cut out Sheela putting her arm on Haria’s shoulders while saying “Main tumko seedha karoongi” (I will put you straight)

Drinking ‘sins’!

– Romance of the High Seas (1948): Delete all

drinking scenes and reduce other drink scenes to

the absolute minimum essential for the continuity of the story

– Whispering Smith (1948): One flash of men and women together in drinking and revelry should be deleted

– Three Daring Daughters (1949): Delete all drinking scenes and reduce other drink scenes to the absolute minimum essential for the continuity of the story

Paarane (2018)

Sreelesh S Nair’s film in Kodava language was rejected by the regional office of CBFC (Kerala) on the grounds that the members who watched it did not like the colour grading and the long duration shots in it. Also, none of the people who watched it knew Kodava, revealed sources. Moreover, another reason they cited was: ‘Coorg can’t look ugly’.

Udta Punjab (2016)

Abhishek Chaubey’s Udta Punjab received flak from the Board because it dealt with the controversial topic of the rampant drug trade in Punjab. The Board wanted all the references to Punjab and elections to be deleted from the film. Also, the word Punjab was said to be removed from the title, leaving it to just Udta!

No Fathers in Kashmir (2019) and Inshallah Football (2010)

Directed by Ashvin Kumar, both the films depicted the tragic lives of those living in Kashmir – a topic which is considered sensitive. This, apparently, was the reason that made it come under the scanner of the Board.

Changing Times

According to a recent data revealed by a Right to Information (RTI) inquiry, the CBFC has banned a total of 793 films in the past 16 years. This was a shocking disclosure. Even after so many years, there have been times when the Board has been “careless”, as many have claimed, while judging a film.

Though, Pahlaj Nihalani might have been ‘dethroned’, but even after Prasoon Joshi took charge as the chairman of the Board – many such controversial disputes have taken place. Let us look at how some of the films of recent times, had to bear the wrath of the Board, creating a lot of stir!

S Durga (2017)

Objections were raised to Sasidharan’s film, citing that it could ‘hurt religious sentiments’ and cause ‘law and order problems’ (by I&B ministry). Later, the then CBFC president Pahlaj Nihalani asked for 21 audio cuts, changed the name from Sexy Durga to S Durga and released it with a U/A certificate.

Lipstick Under my Burkha (2016)

The film, directed by Alankrita Shrivastava, was rejected because: “the story is lady oriented, their fantasy above life. There are contentious sexual scenes, abusive words, audio pornography and a bit sensitive touch about one particular section of society, hence film refused under guidelines,”(this was cited as the reason by the CBFC in their letter).

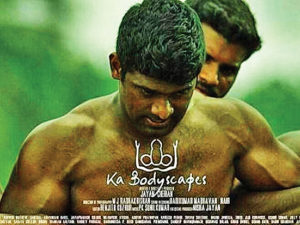

Ka Bodyscapes (2016)

Director Jayan Cherian’s film was rejected for “glorifying” homosexuality, “accentuating vital parts “of the male body, portraying Hinduism in a “derogatory manner” and a scene in which “a female Muslim character is shown masturbating.”

21 Months of Hell (2017)

Malayalam filmmaker Yadu Vijayakrishnan’s 78-minute documentary based on the Emergency period in India was denied certificate on grounds like “violence”, disrespect towards Mahatma Gandhi and the national flag, among many others.

Paanch (2003) and Black Friday (2004)

Anurag Kashyap’s directorial debut Paanch, loosely based on Pune’s Joshi-Abhyankar serial murders (1976-77) was never released. And his film Black Friday, which dealt with the controversial 1993 Bombay blasts, was stalled for three years before finally hitting the theatres.

Gulabi Aaina (2003), Unfreedom (2014) and Fire (1996)

Sridhar Rangayan’s Gulabi Aaina, Deepa Mehta’s Fire and Raj Amit Kumar’s Unfreedom – these three films had one thing in common – they dealt with the issues of the LGBTQI community. And this was enough for it to face objections from the Board.

Bandit Queen (1994)

Shekhar Kapur’s Bandit Queen was held for “cuss words”, “rape sequences” and “frontal nudity”. Also, in an interview, the film’s producer Bobby Bedi said that the CBFC “added more than 100 cuts” in it.

Well, be it the 1940s or 2019 – it seems the scenario hasn’t changed much. Even though several clarifications have been made, stating that the work of the Board is to ’certify’ and not ’censor’ – but there’s a fine line between these two. However, one can hope for better days to come – a day when films will be free from unnecessary and unreasonable censoring and monitoring. After all, what we see and how we see things should not be controlled by someone else.