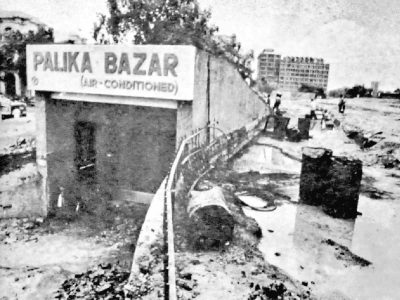

Crica late 1970s: A young Janata Party MP from Bihar often visited his close friend at his Kasturba Gandhi Marg office. Afterward, the duo would venture into the newly opened Palika Bazaar for shopping. The first time MP invariably purchased clothes and toys for his wife and children from the “Thandi Market,” as he fondly called it, before returning to Bihar. That young MP was none other than Lalu Prasad Yadav.

Veteran journalist Aroon Kumar recalls, “Not only Lalu ji, but almost all my friends and relatives from Bihar visited Palika Bazaar during their stay in Delhi. As it was a fully air-conditioned market, there was a huge craze among locals and outsiders to visit there.”

More than 45 years later, much has changed. While Palika Bazaar is no longer the top choice for shoppers, it still draws a significant number of visitors daily. The New Delhi Municipal Council (NDMC) is actively working to improve the overall facade of Palika Bazaar in Connaught Place. By the end of the month, NDMC hopes to complete the terrace renovation, featuring a granite pathway for walking and jogging, seating areas, LED-lit footpaths, and grassy expanses. Stainless steel railings have been installed, and saplings have been planted to beautify the space.

Also read: Delhi: Illegal sand mining continues unchecked, damage Yamuna

The heyday of Palika Bazaar

While shoppers patronised Palika Bazaar from its inception, the Asian Games held in Delhi in 1982 (Asiad ’82) significantly boosted its popularity. People from across Delhi flocked to the market. At the time, many came and settled in the capital. Gurgaon and Noida were not yet fully developed. By the mid 1980s, the audio and video cassette business was booming in Palika Bazaar.

“As a result, many gift and garment shops in the central hall of Palika Bazaar, recognising the changing trends, started selling electronic goods,” recalls Manoj Sehgal, who owned a jeans showroom there.

In the late 1990s, Palika Bazaar became the largest market for video cassettes of Bollywood and Hollywood blockbusters. It also became a source for Walkmans, cameras, and digital diaries brought from Dubai, Hong Kong, Thailand, and Singapore, available at wholesale prices. These were often smuggled goods. Customers from Delhi and neighbouring states visited Palika Bazaar to purchase them. This was the pre-economic liberalisation era, and many other foreign products were also available.

The art of bargaining

Palika Bazaar has approximately 425 shops. While Connaught Place boasts several markets, Palika Bazaar sees fewer local shoppers compared to visitors from outside Delhi.

Praveen Vashishta, a teacher from Meerut, states, “Even though we now have good malls and markets, I still visit Palika Bazaar whenever I come to Delhi. The best thing about Palika Bazaar is that you can bargain endlessly with shopkeepers.”

Yes, bargaining is the hallmark of Palika Bazaar. All goods available in the market were sold only after intense haggling—there was no concept of fixed pricing.

“In the summer months, people would just wander around here to escape the harsh rays of the sun,” says Roopam Sehgal, a businessman from East Delhi who used to visit with his mother and friends.

Adapting to change

Until 2000, almost all shops in the Central Hall and Mezzanine Floor of Palika Bazaar sold video and audio cassettes. Now, electronic goods and garments dominate. Unlike other markets where shopkeepers tend to stick to their trade, Palika Bazaar has seen frequent changes.

Some former “cassette kings” now run snack shops or have ventured into the garment business.

“In its early years, Palika Bazaar was a revolutionary destination. Built during the Emergency period under the vision of Sanjay Gandhi, it was a bustling hub for the upper middle class and trendsetters seeking imported luxury goods, such as Levi’s jeans, perfumes, electronics, and music cassettes—items that were scarce in pre-liberalisation India. In the early years, it also served as an informal forex hub, catering to travellers navigating strict foreign exchange restrictions,” says Pritam Dhariwal, an old hand at NDMC who has witnessed the making of Palika Bazaar since its early days.

The impact of economic liberalisation

The 1990s marked the beginning of Palika’s decline as India’s economic liberalisation in 1991 opened the market to global brands and modern retail formats. Shopping malls and branded stores began to emerge, offering better aesthetics, variety, and authenticity—advantages Palika struggled to match. Its once unique air-conditioning became commonplace elsewhere.

The market’s reputation also shifted, becoming infamous for selling counterfeit goods, pirated CDs/DVDs, and even illicit items like pornography, despite regular police raids. This pivot to low cost, often dubious products alienated some of its original clientele while attracting bargain hunters and tourists.

By the 2000s and 2010s, Palika Bazaar had transformed into a shadow of its former self. While it still drew an estimated 15,000 visitors daily, many came for cheap clothing, electronics, and accessories—or simply to enjoy the cool air—rather than for a premium shopping experience. The rise of e-commerce further eroded its customer base, as online platforms offered convenience and competitive pricing without the need for aggressive bargaining, a hallmark of Palika’s shopping culture.

Also read: Patriot impact: Authorities launch a crackdown on illegal dyeing units in Delhi

Nostalgia and an uncertain future

Today, in 2025, Palika Bazaar remains a paradoxical entity. It retains a nostalgic charm for Delhiites who recall its heyday and continues to attract budget shoppers, students, and tourists seeking deals on trendy clothes, gadgets, and knockoffs.

The NDMC’s ongoing plans for a “regeneration” aim to address its state of decay, but competition from modern retail and online shopping poses a formidable challenge.

“Palika’s evolution mirrors Delhi’s own transformation— from a city with limited retail options to a sprawling metropolis of malls, metros, and digital commerce—leaving the bazaar as a relic of a bygone era, clinging to relevance through affordability and its unique underground identity,” says author Subodh Mishra, who used to visit almost daily in the early 2000s when his office was located in Connaught Place.

The writer is a Delhi-based senior journalist and author of two books ‘Gandhi’s Delhi: April 12, 1915-January 30, 1948 and Beyond’ and ‘Dilli Ka Pehla Pyar