Every year millions of people migrate from small towns to big cities in search of better living and most of them end up as day labour, domestic helpers and street vendors.

Metropolitan cities like Delhi have nearly five lakh domestic workers, according to National Platform for Domestic Workers (NPDW).

Women employees are often victims of sexual harassment and assault.

The recent case of abuse of a domestic helper in a workplace in Noida has brought to light the perils faced by women workers, especially in the unorganised sector.

Anita, a 20-year-old woman, was beaten up by her employer Shefali Koul, an advocate, in Cleo County of Noida, Sector – 120.

The case came into limelight when a CCTV footage showing Shefali beating and forcibly dragging her helper in a building’s elevator went viral.

Also read: A cut below the rest

“She used to beat me and douse me with cold water every day. I had eaten a bar of jaggery on December 26, so I was beaten with slippers. Then she threatened to set fire to me and throw me off the roof,” complained Anita.

“So, I climbed down from the fourth floor by tying several dupattas end to end to form a rope. The society guard stopped me and called madam (Shefali) and then madam dragged me upstairs and started beating me,” added Anita.

Anita had joined in April and her contract ended in October but they refused to release her.

“I was not allowed to go home nor was I allowed to talk to my family.”

According to the police, Shefali Koul was initially charged under Indian Penal Code Sections 344 (illegal confinement for more than 10 days), 323 (voluntarily causing harm) and 504 (insult). The case has now been amended to include charges under Section 308 (attempt to commit culpable homicide) and the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act.

Domestic workers are an integral part of the daily life of a large section of India’s urban population.

They are defined by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) as those who perform domestic work for pay and remuneration (ILO 2018). Their work includes a variety of domestic services such as sweeping, cleaning, laundry, maintenance work, driving and security, among others.

Meenakshi, a 49-year-old domestic worker living with her husband and two children in the slums of Patel Nagar, said, “Before the first lockdown, I used to earn Rs 10,000 per month working in three houses. During the lockdown, we were forced to stay at home for several months without pay. We made it through three waves of Covid, but my monthly income has been cut by half compared to pre-Covid levels. I’m facing financial difficulty. We lack a proper network for finding work. Our jobs are poorly regulated, and we are denied social security benefits. Some of our employers treat us badly.”

Conflicting policy action

Domestic workers were first regulated by a policy in 1959, when the Rajya Sabha and Lok Sabha passed the Domestic Workers (Conditions of Service) Bill, a private member’s bill, and the All India Domestic Servants Bill, respectively. These bills addressed a variety of issues, including minimum wage, maximum working hours and local police registration of domestic workers.

Two more private member bills were introduced in the Lok Sabha in 1972 and 1996.

These bills emphasised the importance of bringing domestic workers under the jurisdiction of the Industrial Disputes Act 1.

Aside from these bills, the House Workers (Conditions of Service) Bill, which focuses on the need for every employer to contribute to a House Workers’ Welfare Fund was formulated in 1989 (Mann 2015).

In 1989, a legislation requiring all employers to contribute to a House Workers’ Welfare Fund was enacted (Mann 2015).

“However, none of the bills mentioned above were passed. Domestic workers in India are currently exempt from critical national labour laws such as the Factories Act 1948 and the National Minimum Wage Act 1948, thanks to the exemption of the Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act,” said an NGO official aware of the subject.

The domestic workers are unhappy too.

“We are underpaid and there are no defined work timings,” said Satnam Kaur, who works in Kasturba Nagar.

“When we demand a raise and our employers hire someone else at a lower salary, we are frequently harassed. We want the government to ensure that the minimum wage is paid.”

Raziya, 36-year-old who hails from Bengal, works in Jamia Nagar, Okhla, nowadays.

“I faced discrimination over religion and caste at the workplace. I was not given work in some houses in Noida because of my religion. Many times, if there was no madam at home, I would not go to work because I was afraid something might happen,” she complains.

There is no doubt that the demand for domestic workers is increasing. Their workload is also increasing.

“We see that the work of the domestic worker is increasing. Nowadays, both husband and wife work, so they keep the domestic helper at home. People migrate to a city like Delhi every day. For women, who are not educated, the work of a domestic worker is easy to get. That’s why most domestic workers are women. All of them come and work only through acquaintances or relatives,” said the NGO official, who did not wish to be named.

“The number of domestic workers has increased in metropolitan cities like Delhi. Because there is no employment in the village, women feel they will take care of the house after working for 3-4 hours. In this way, they also get a little income. The biggest problem is that under any law, their name is not mentioned as a worker, so there’s no recognition for such workers, because the government has not recognised it as a profession.”

Status of national laws relating to domestic workers in India

– Ratified Right to Organise Convention (Absent)

– Ratified Freedom of Association (Absent)

– Domestic Workers Legislation (Absent)

– Included Under Labour Legislation (Pending)

(SOURCE: A HANDBOOK ON DOMESTIC WORKER RIGHTS ACROSS ASIA, 2010)

Domestic workers have been covered by laws such as the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act 1986 (as amended in 2006), the Unorganised Social Security Act 2008, and the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal) Act 2013.

Some Indian states have amended specific provisions through welfare boards to facilitate social security benefits for domestic workers. However, existing laws are still fragmented and insufficient.

Placement agencies

Placement agencies, which act as intermediaries or middlemen in facilitating the recruitment process between domestic workers and employers, have grown dramatically in recent years. Some ‘formalised’ agencies are supported by cooperative societies, trade unions, or voluntary organisations.

However, it has been reported that several placement agencies are not registered and operate solely for profit (Neetha 2009).

These organisations mobilise large number of women, particularly young and unmarried girls from rural and tribal areas, who speak little or no English.

Most of these agencies do not provide assistance to domestic workers during illness or interim stays in the absence of their employers, nor do they ensure domestic workers’ safety on the job.

Because there is no national law in India to regulate placement agencies, domestic workers are vulnerable

to exploitation by both middlemen as well as employers.

To close this gap, the Delhi Government drafted the Delhi Private Placement Agencies (Regulation) Bill, 2012, which establishes strict laws requiring mandatory registration of all placement agencies, as well as one kin of the domestic worker (Chigateri 2016). However, this Bill has been criticised for failing to include a legal mandate requiring employers to register alongside domestic workers.

Characterisation of the domestic work industry

Article 1 of the ILO Domestic Workers Convention, 2011 (No. 189) states:

(a) The term “domestic work” refers to work done in or for a household or households; (b) The term “domestic worker” refers to any person who performs domestic work as part of their job.

(c) A person who does domestic work only occasionally or sporadically and not on a regular basis is not a domestic worker (Chigateri et al. 2016: 95).

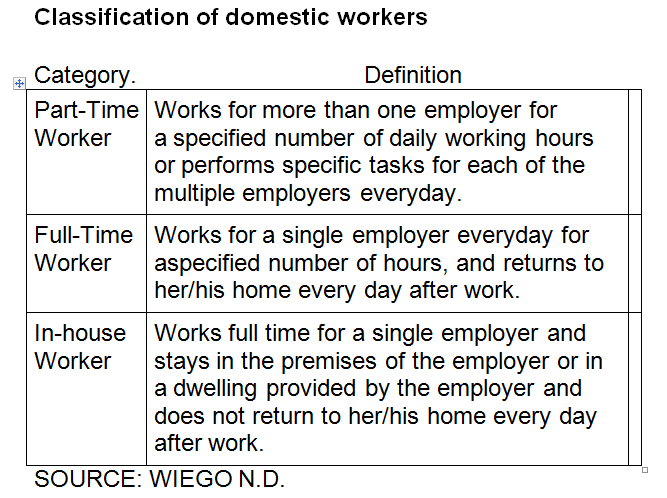

Domestic workers were classified as Category 9 – personal, social, and community services (under National Industrial Classification (NIC) 3), according to the International Labour Organization’s International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO). Domestic workers are classified as part-time, full-time, or live-in workers based on their working hours and nature of employment (Table 1). (Chigateri 2016, WIEGO n.d.).