White-cladded corpses remain suspended mid-air in a charred house as our protagonist Chhadami, a vendor in Old Delhi, wakes up from a nightmare.

“Something must have happened to my grandson,” he quivers as he wakes up amid the bustling, overcrowded streets of Old Delhi.

The area, historically known as Shahjahanabad, encompasses layers of lives and history meshed with contemporary urban struggles and ambitions.

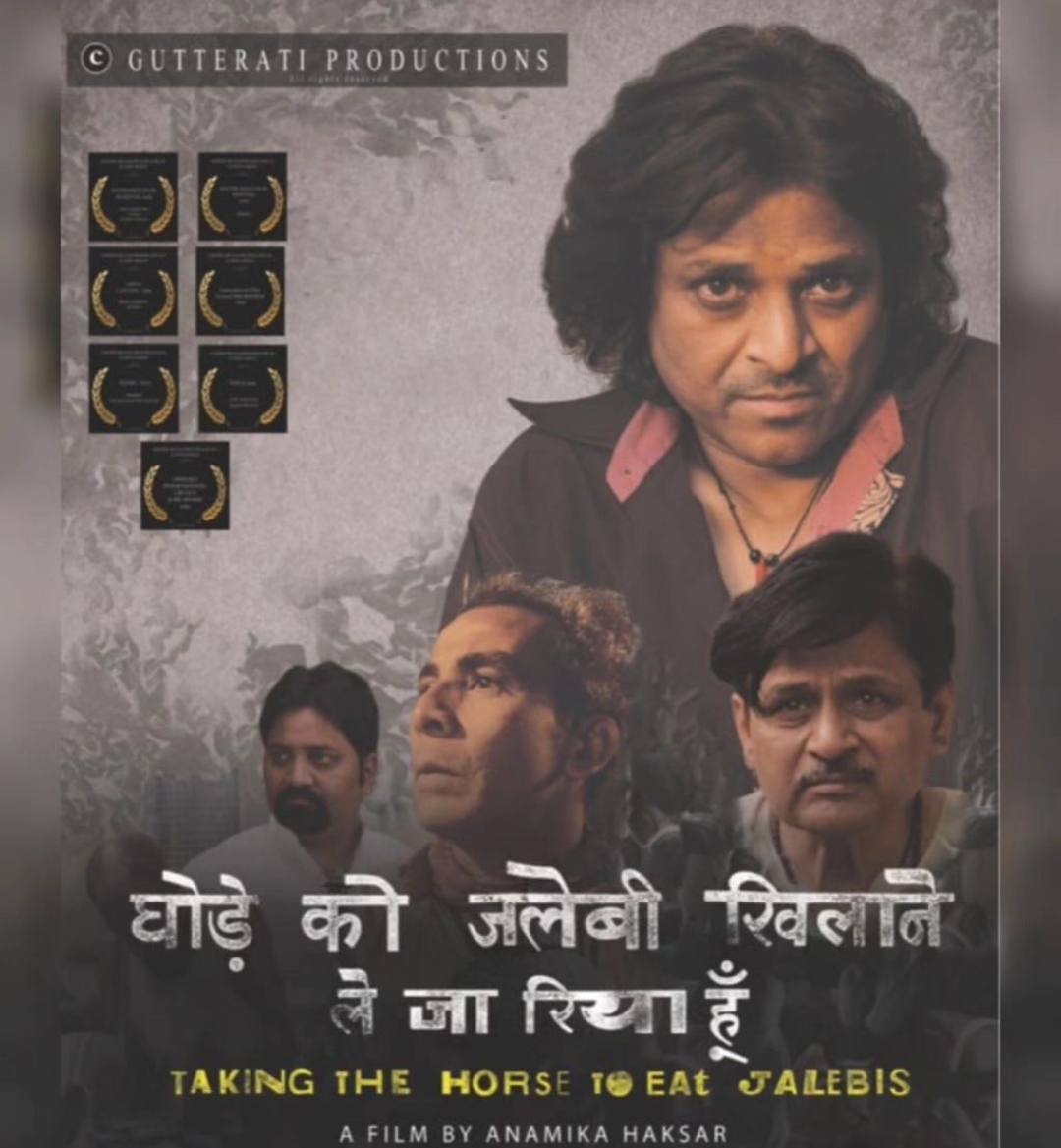

“I realised that theatre alone could not have captured all these visual layers. I needed the lens to capture what people living in this place think,” says film director, Anamika Haksar. This is what she has successfully envisioned through her directorial debut on the silver screen, Ghode Ko Jalebi Khilane Le Ja Riya Hoon.

A passion project which began in the 1990s with a series of social surveys on Delhi’s migrant populations, it introduced Anamika to the most valuable asset that many of these migrants have — their dreams.

“These people who have come from far-flung areas and now add to the labour and progress of this city have a very rich psychological landscape,” she says. “Many survey responses would take more than a year.”

According to her, most of her respondents worked very long, excruciating hours in factories. The film, born out of seven years of rigorous documentation on the lives of street people in Old Delhi has beggars, pickpockets, loaders, small-scale factory workers, street singers and vendors making their presence felt.

Breaking traditional barriers and not following a conventional linear structure to better portray fluid dreams, the movie uses animation, documentary footage, fictionalised characters and an immersive sound design to charm the audience. The film’s fictional dialogues, written by Lokesh Jain who also stars in the film, ground the story and introduce the audience to the lingo and colloquialisms used by the residents of the old city.

“I feel I have a very old connection to Shahjahanabad, my ancestors travelled from Kashmir to reside in the area. My husband also happens to be from the old city, so I was privy to the intricacies of the area in some way,” she says cheekily.

The film stars theatre stalwarts Ravindra Sahu as Patru, a pickpocket; Raghubir Yadav as Chhadami, a vendor; K Gopalan as Lalbihari, a loader; and Lokesh Jain as Akash Jain, a tourist guide.

These characters, set in the alleys of Old Delhi, traverse a changing landscape where modern sanitation pipes reside alongside beautiful medieval Mughal architecture. The characters often find themselves at the mercy of their circumstances. Patru finds himself at odds with an honest living as he struggles to make ends meet and pickpockets weddings and bystanders, Chhadami’s business suffers as malls and modern construction invade Shahjahanabad, Lalbihari’s long quest for labour justice remains unheard and Akash Jain battles bigoted opinions as he introduces tourists to the culture, poetry and architecture of a once fabled place.

Shahjahanabad is a crowded city where migrants belonging to different castes, creeds and religions come together to earn a living and wherein their dreams even overlap.

“We changed the animation approach according to the nature of these dreams,” says Anamika.

With the help of cinematographer, Saumyananda Sahi, and animation and special effects specialist, Soumita Ranade, as well as Archana Shastri, production designer for the movie, these dreams were materialised employing diverse techniques such as hand drawings, documentary footage and traditional techniques such as Madhubani paintings to name a few.

Throughout the movie, the audience meets known and obscure figures from the old city. Abandoned widows, real waste workers, women residing on roads, to name a few, narrate their painful stories.

“It was paramount to us that the movie involves vulnerable people of our society and we made sure that they were able to access theatres for the screenings,” stresses Anamika over a phone call.

She says that she did not want the movie to become inaccessible to the subjects themselves, claiming, “I would plant people known to me in screenings so that street dwellers would not be turned back.”

The movie, initially premiered in MAMI (Mumbai Academy of Moving Image), was commercially released in 2022 with the help of Shiladitya Bora and Platoon One Films. The movie continues to be screened at various venues. A screening conducted earlier this month by artist collective, W.I.P Labs, attracted a houseful attendance at Alliance Française de Delhi.

This correspondent saw the movie sitting on a floor in a packed theatre as audiences laughed, cheered and jeered with the characters.

“The movie seems to impact audiences as the dialogues have been taken from real-life people,” says Anamika.

A tear-jerking scene where Patru, when asked what he would do if he were given a crore rupees, was inspired from a conversation with a real pickpocket.

“During the interview, we asked him what he would do if he had that much money and to our surprise, he said he would distribute it to the widows and street children. We were deeply touched,” she says.

The movie, though projecting a tale of migrants in a historical city, is by no means a tale of tragedy.

Audiences laugh as our street-smart characters negotiate space, authorities, polarisation and modernity. The much talked about colourful and vernacular title of the movie stems from a humorous incident in Anamika’s teenage years.

“A relative of mine was waiting for a tonga in the old city. As she called a passing tonga, the driver replied rather cheekily that he could not take her as the horse needed to be fed jalebis. For some reason, this incident has stayed with me all these years,” she laughs.

Sitting amid the demographically diverse audience at the screening, Vasu Anand (26), who works at an advertising agency, promises that he would attend future screenings as well.

“I have visited Old Delhi numerous times for the lovely food and monuments, but never had I considered it to be such a dynamic place,” says Vasu.

He mentions that the visuals of the movie would stay with him for a long time.

Geeta Misra, who runs an NGO with a focus on feminist issues, applauds the real lives projected in the movie.

“A lot of what happens in the film is part of my everyday work. The documentation of these lives by the director is simply on point,” she exclaims.

The movie, though acclaimed at international film festivals, fights the narrative of folk tales as expected from India.

A twist on the popular heritage walks of Old Delhi plays out on the screen as Patru introduces tourists and history lovers to the underbelly of the old city. Shots of beggars being shoved into vehicles to be removed, unclaimed corpses being picked from cold streets or make-shift shops with full families residing in them question the audience’s perspective on what they might know about Shahjahanabad.

A twist on the popular heritage walks of Old Delhi plays out on the screen as Patru introduces tourists and history lovers to the underbelly of the old city. Shots of beggars being shoved into vehicles to be removed, unclaimed corpses being picked from cold streets or make-shift shops with full families residing in them question the audience’s perspective on what they might know about Shahjahanabad.

Anirban Ghosh, co-founder of W.I.P Labs, says, “Anamika ji’s movie successfully bridges surrealism with grounded realities of our time. This movie will have a cult following and shall be relevant for years to come,” he says.

Asked if the historically important city of Old Delhi (Shahjahanabad) has been given justice in the visual medium, Anamika laments, “The tale of migrants, the tale of nuanced cultures have somewhat disappeared from our movie platter. The story of India is one where different ideologies, lifestyles, eating habits and philosophies come together to share this beautiful land. We must strive to keep it that way.”