How many Delhiites know that where Connaught Place now thrives, a village named Madhoganj existed until around 1920? Or that the Delhi Legislative Assembly building (the Old Secretariat) stands on land that once belonged to Chandrawal village? Chandrawal was razed after its Gujjar inhabitants fiercely resisted British forces during the 1857 uprising. Those displaced later re-established the village near the Delhi University main campus.

Similarly, how many residents are aware that the Parliament House, Rashtrapati Bhavan, and the North and South Blocks were all built on the remains of Raisina village? This wasn’t too long ago—just around 125 years. Farming was once practised there, but today, nothing of Raisina remains except a road named Raisina Road, now lined with bungalows housing MPs and ministers. Atal Bihari Vajpayee lived here for decades.

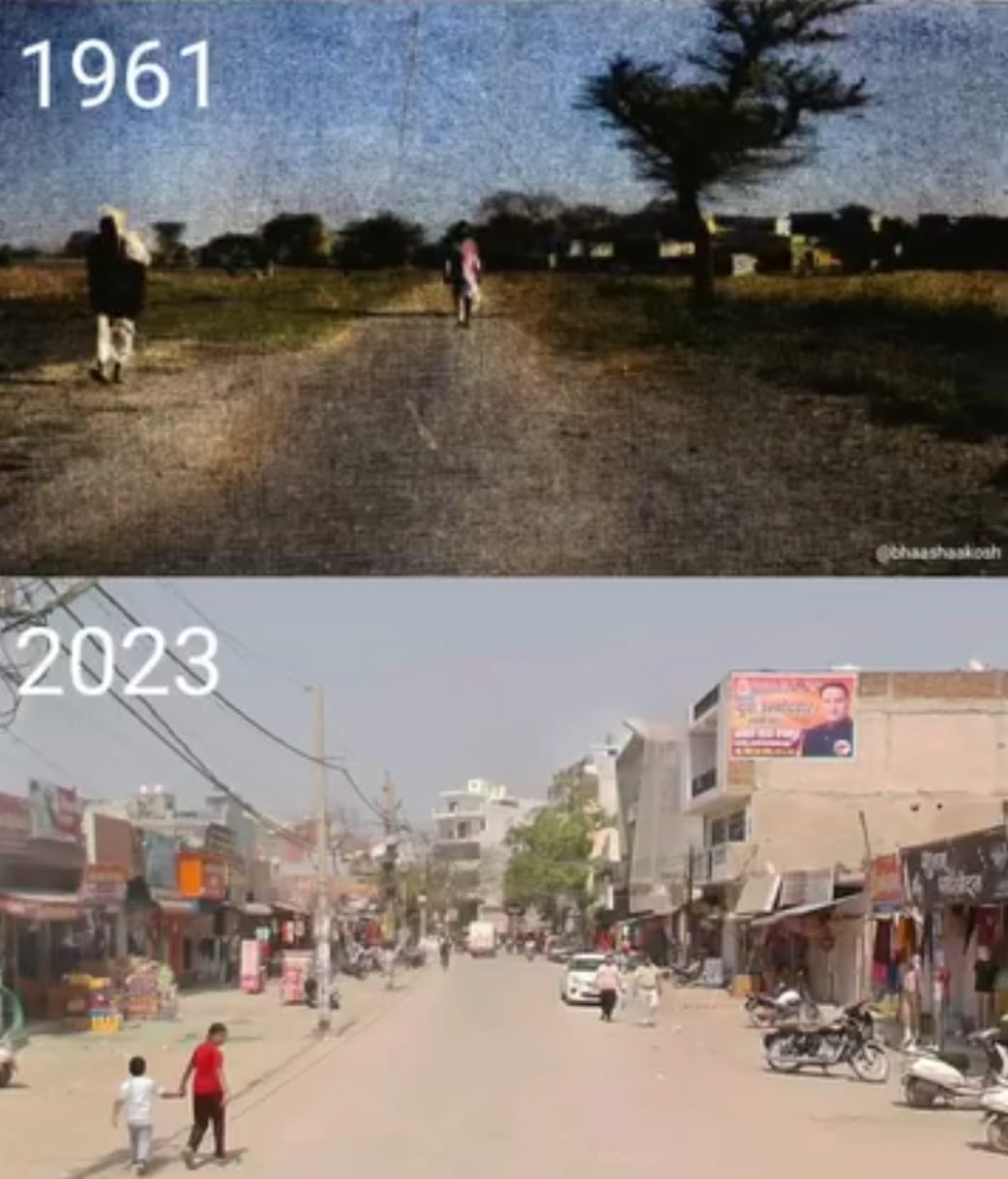

Official records still list 357 villages in Delhi, each with its own unique character and social fabric. These communities have retained their customs and traditions, yet in-depth research on rural Delhi has remained largely absent.

The Delhi Dehat project

Seeking to fill this gap, three young men—Puneet Singh Singhal from Deoli (South Delhi), Gagandeep Singh from Madanpur Khadar (South-East Delhi), and Parth Shokeen from Nilothi (West Delhi)—have launched a documentation initiative called Delhi Dehat, focused on preserving the oral histories and cultural memory of Delhi’s villages.

All in their early 30s, they come from families with roots in Delhi going back four to five centuries. Their ambition is to document Delhi’s rural heritage—a task that had not been undertaken until now.

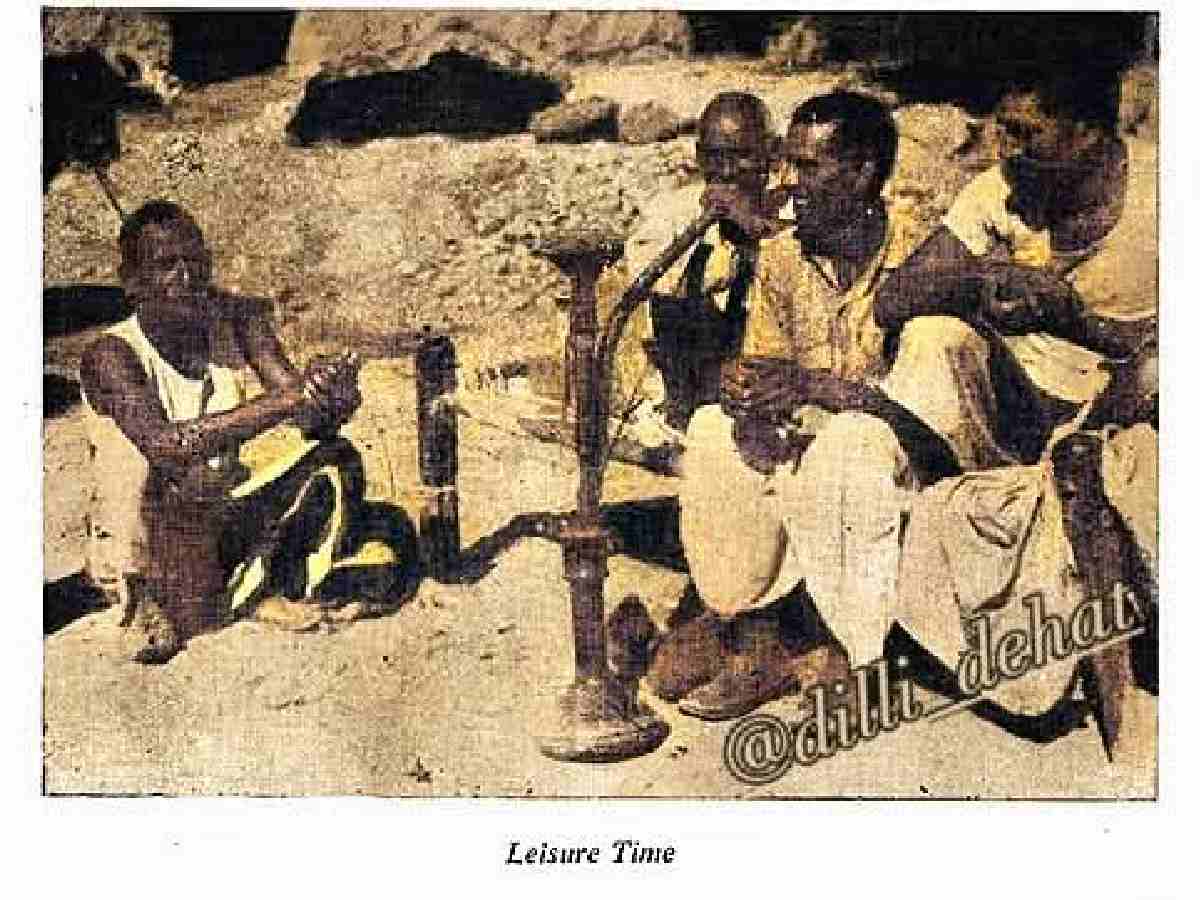

“We are going from village to village, meeting the villagers, and recording information about their village, society, culture, history, and so on,” says Puneet. “We are collecting old photographs that tell the story of Delhi’s villages. This is all being done according to oral tradition.”

“We are going from village to village, meeting the villagers, and recording information about their village, society, culture, history, and so on,” says Puneet. “We are collecting old photographs that tell the story of Delhi’s villages. This is all being done according to oral tradition.”

Also Read: Valmik Thapar, the tiger conservationist’s little known side

Delhi’s villages have witnessed the rule of the Pandavas, Rajputs, Sultans, and Mughals. Each era has left its mark on their socio-cultural fabric. For instance, the Qutub Minar and its surroundings reflect early Islamic influence, while the narrow lanes and havelis of Old Delhi provide a window into Mughal-era architecture and lifestyle.

Jonti: The village of India’s Green Revolution

Any conversation about the Green Revolution is incomplete without mention of Jonti village in North Delhi. Improved wheat seed varieties were developed at the Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), Pusa, to boost production. A decision was then made to test these seeds in a village setting, and Jonti was chosen—primarily because of its access to canal irrigation.

“How many Delhiites even know of this village’s importance?” the team asks.

Hundreds of agricultural scientists now work at IARI, which itself stands on the land of the erstwhile Shadipur Khampur and Dasghara villages.

“Both these villages still exist, although they have been urbanised,” says Gagandeep. “Farming is no longer practised, but they still have Chaupals and Panchayats. You could say that we are preserving the history and present of Delhi’s villages through oral tradition. This work should have been done earlier, but we are happy that we are doing it selflessly.”

Beyond nostalgia: Reclaiming a neglected legacy

The Delhi Dehat project is not limited to nostalgia. It documents everything—from fields and Chaupals to local deities, temples, dried-up Johads (traditional ponds), and even ruins hidden behind metro stations.

Parth poses a critical question: why are Delhi’s villages so often ignored? “When discussing Delhi’s identity, why are its villages left out? Institutions like JNU, IIT, Indira Gandhi International Airport, and many other areas were built on village land—often without the consent of the villagers,” he notes. “Entire communities were uprooted, and no initiative was taken to preserve their social and historical legacy.”

But the three men behind Delhi Dehat are attempting to correct that oversight. They are involving villagers, historians, and urban planners to build a fuller picture of Delhi’s rural past and present.

“Delhi Dehat is not mere nostalgia,” says Gagandeep. “Delhi’s villages are the life and soul of the nation’s capital. Their existence is still intact. We belong to these villages. We are encompassing the historical periods of Delhi’s villages from ancient times to the modern era.”

Villages like Mehrauli, Hauz Khas, Najafgarh, and Bawana hold archaeological remains, ancient temples, mosques, and forts tied to the Delhi Sultanate, Mughal period, and even the Mahabharata era. These villages have preserved their culture and way of life through various regimes.

Preserving heritage for future generations

Documenting the history of these villages amid the chaos of a modern metropolis will offer future generations valuable insights into this often-overlooked region.

Gagandeep, whose family has lived in Madanpur Khadar for over 600 years, says that Sarita Vihar stands on land that once belonged to his village.

Gagandeep, whose family has lived in Madanpur Khadar for over 600 years, says that Sarita Vihar stands on land that once belonged to his village.

The Delhi Dehat project, through its oral history efforts and grassroots involvement, offers a meaningful way to understand the cultural diversity, social cohesion, and historical significance of Delhi’s rural heartlands.