Delhi has long witnessed a disturbingly high number of missing persons cases. Yet, consistent with recent trends, the national capital has seen a dip in such incidents in 2025. Between January 1 and July 12, the city recorded approximately 9,200 cases of untraced missing persons, according to data from the Zonal Integrated Police Network (ZIPNET). During the same period in 2024, the figure stood at around 12,200—though this includes repeated entries, officials noted.

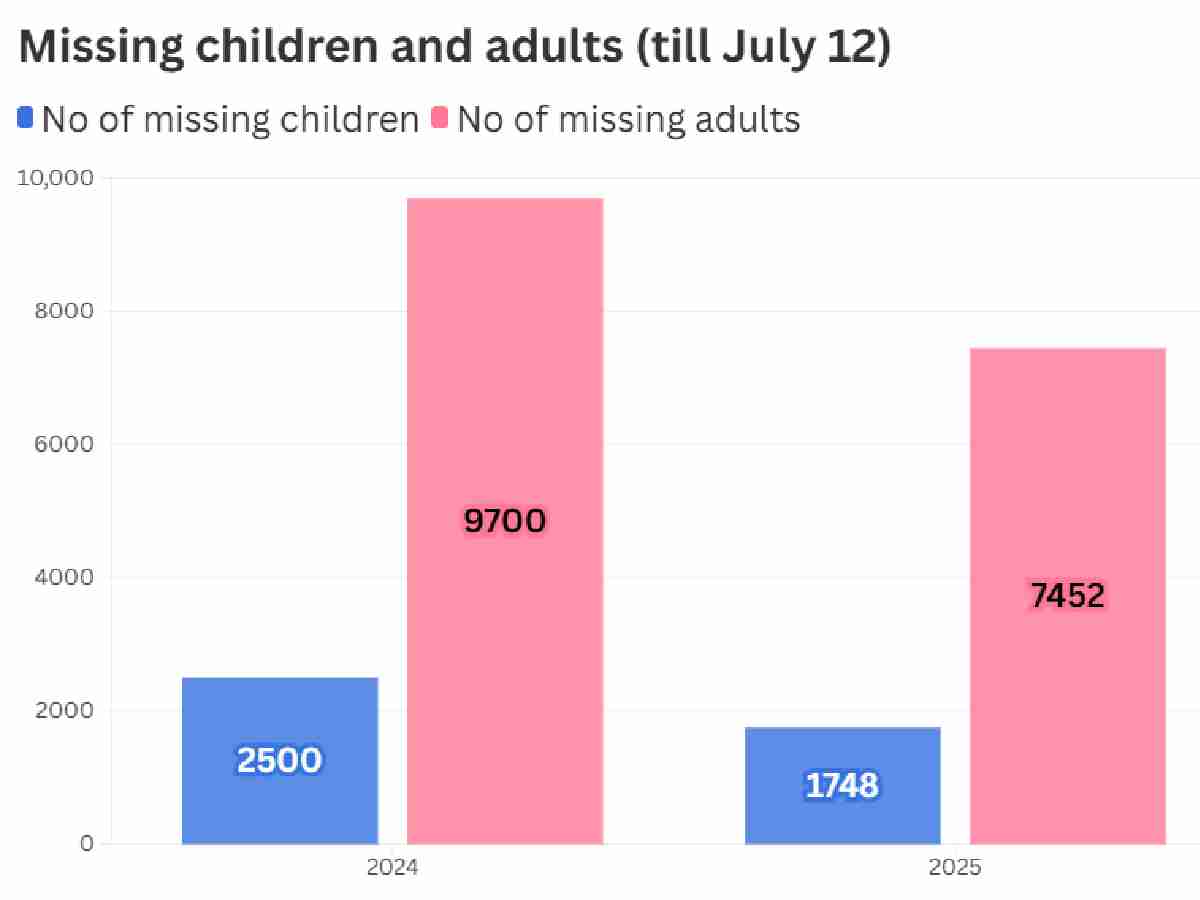

Despite the overall decline, a striking imbalance remains in the profile of the missing. More adults continue to go missing than children, and the ratio between the two is widening.

“On average, around 2,500 children went missing in 2024. This year, that number has dipped slightly to about 1,748 during the same period. Although the absolute numbers are decreasing, the proportion of missing adults remains significantly higher,” a senior police official said.

In 2025, for every child who went missing, over four adults did. In contrast, the previous year recorded a ratio of roughly three adults for every missing child—indicating a modest but telling increase.

Police officials have attributed the declining numbers to several factors, including increased vigilance, enhanced tracking systems, and improved collaboration with NGOs. “We’ve launched comprehensive efforts to tackle human trafficking,” said a senior police officer. He added that dedicated teams, better surveillance, and the strategic use of CCTV cameras have “greatly improved our ability to trace missing persons and prevent trafficking.”

Even in 2024, the number of untraced missing persons had dropped—22,040 cases were recorded compared to 24,356 in 2023, reflecting a 9.5% decline. Yet, the ratio remains stark: for every individual located, two others remain untraced.

This year, Delhi Police has recovered 8,342 missing individuals—down from 12,609 last year. While these figures reflect progress, they also expose persistent gaps in the system.

Role of Anti-Human Trafficking Units

One of the key contributors to the reduction in trafficking cases has been the Anti-Human Trafficking Units (AHTUs) under Delhi Police. Launched as part of a 2010 Ministry of Home Affairs scheme, the AHTUs were created to address human trafficking through a coordinated, systemic approach.

The scheme mandated the establishment of specialised units in every district, focusing on prevention, rescue, rehabilitation, and prosecution. These units conduct raids, rescue operations, and offer survivors counselling and vocational training. They also pursue legal action against traffickers.

Each AHTU comprises trained inspectors, sub-inspectors, and constables who work in close coordination with NGOs, social welfare departments, and other stakeholders. This integrated model has enabled police to dismantle complex trafficking networks with greater accuracy and efficiency.

AHTUs also spearhead Operation Muskaan, a flagship initiative aimed at rescuing trafficked children. As of October 30, 2024, 989 children were rescued in 97 cases last year, compared to 1,257 children in 126 cases in 2023. Many of the rescued children were subjected to exploitative labour, working long hours in hazardous conditions for meagre wages.

While the dip in numbers may suggest success, the persistence of child labour remains a major concern. NGOs warn that the issue is far from resolved and that traffickers are evolving their methods.

“We are working tirelessly to reduce trafficking incidents in Delhi. Increased surveillance and strategically placed AHTUs have enabled us to crack down on trafficking networks,” said Sanjay Bhatia, Additional Commissioner of Police, Crime Branch.

The changing face of trafficking

A new and more insidious challenge has emerged: placement agencies exploiting legal loopholes to employ minors. These agencies often place children as domestic workers in households or businesses, where they are paid paltry sums and subjected to exploitative conditions.

According to Delhi Police, intra-city child trafficking is relatively uncommon. However, Delhi’s geographical position near Gurugram and Noida has turned it into a hub for trafficking. Many trafficked children are brought into the city and pushed into forced labour—often with placement agencies playing a pivotal role.

The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, prohibits the employment of children under 14 years and restricts hazardous work for those aged between 14 and 18. Yet, violations continue with alarming regularity.

On October 24, 15 children aged between seven and 17 were rescued from a toy factory in Karawal Nagar, north-east Delhi. They had been forced to work 12-hour shifts for just Rs 500 a week and were reportedly subject to physical abuse.

Raids conducted on August 5 and 6 also led to the rescue of 73 children—18 from a jute factory in Bhajanpura and 55 from another toy factory in Narela-Bawana.

Such operations are often conducted in collaboration with child rights NGOs. Rakesh Kumar of Bachpan Bachao Andolan explained, “Our role involves identifying factories and workplaces employing children. We conduct reconnaissance to locate these sites and inform the police. We also participate in raids to help apprehend offenders.”

Naved Anjum of Prayas Juvenile Aid Centre added, “While trafficking cases have decreased, traffickers have found ways to exploit loopholes. Placement agencies play a significant role by paying parents to ‘sell’ their children or posing as relatives to gain custody.”

Also Read: River of grief: Suicides in Yamuna highlight gaps in public safety

Anjum also pointed out that many trafficking cases are now reclassified as kidnappings, possibly contributing to the lower reported figures. “It’s no longer as straightforward as it once was. Brothels now often consist of workers who are not abducted but sent by their families or arrive voluntarily,” he said. “Placement agencies, however, lure families with money or disguise themselves as relatives to get children to work.”

How Delhi Police is locating the missing

In the southwest district, Delhi Police recently carried out a month-long coordinated operation from June 1 to June 30. Multiple police stations—including Kapashera, Sagarpur, Palam Village, Vasant Kunj South, and Kishangarh—participated.

Officers used CCTV footage, conducted local inquiries, and verified details at bus stops and other transport hubs. They also consulted bus drivers, conductors, street vendors, and informers. Photographs of the missing were circulated widely and cross-referenced with hospital and police records.

The initiative resulted in the recovery of 521 missing persons since January 1, including 149 children and 372 adults.

The initiative resulted in the recovery of 521 missing persons since January 1, including 149 children and 372 adults.

The station-wise breakdown of notable recoveries is as follows: Kapashera traced 5 children and 28 adults; Sagarpur 10 children and 20 adults; Palam Village 4 children and 20 adults; Vasant Kunj South 3 girls and 10 adults; Kishangarh 8 children and 3 adults; Safdarjung Enclave 1 boy and 10 adults.

The Anti-Human Trafficking Unit found 11 children; Vasant Vihar traced 6 girls and 3 women; R K Puram located 9 people; Delhi Cantt recovered 2 girls and 4 adults; Vasant Kunj North found 1 girl and 4 adults; Sarojini Nagar traced 1 girl and 3 adults; and South Campus recovered 1 woman.